Due to a history of systemic racism, discrimination, and segregation, BIPOC and low-income communities are more likely to live in areas that are disaster-prone, with under-invested infrastructure, and closer to polluting energy facilities like power plants. Addressing these disparities requires a focus on energy justice, the principle that access to energy that is reliable, affordable, and clean is a basic right. To achieve energy justice, historically marginalized individuals and communities must not only have access to energy meeting these criteria, but greater control over both the systems and the decision-making process to procure and manage that energy.

We began this series by defining distributed energy resources (DERs) and the rapid evolution they’re driving in the traditionally centralized grid. Then we talked about two different ways DERs can be combined—locally in a microgrid to enhance resilience, or broadly in a virtual power plant (VPP) to enhance DER value while providing most of the same benefits as traditional power plants. To close, we’ll focus on the role of DERs in advancing energy justice.

What does energy justice require?

There are five basic principles necessary for achieving energy justice: energy must be clean, affordable, reliable, locally controlled, and accessible. DERs can be a critical part of achieving energy justice because they fulfill most of these requirements—but as we’ll see, availability remains a challenge; while BIPOC and low-income communities have a greater need for the benefits of DERs, the historical context means they face more obstacles to obtaining them.

What distributed energy resources provide

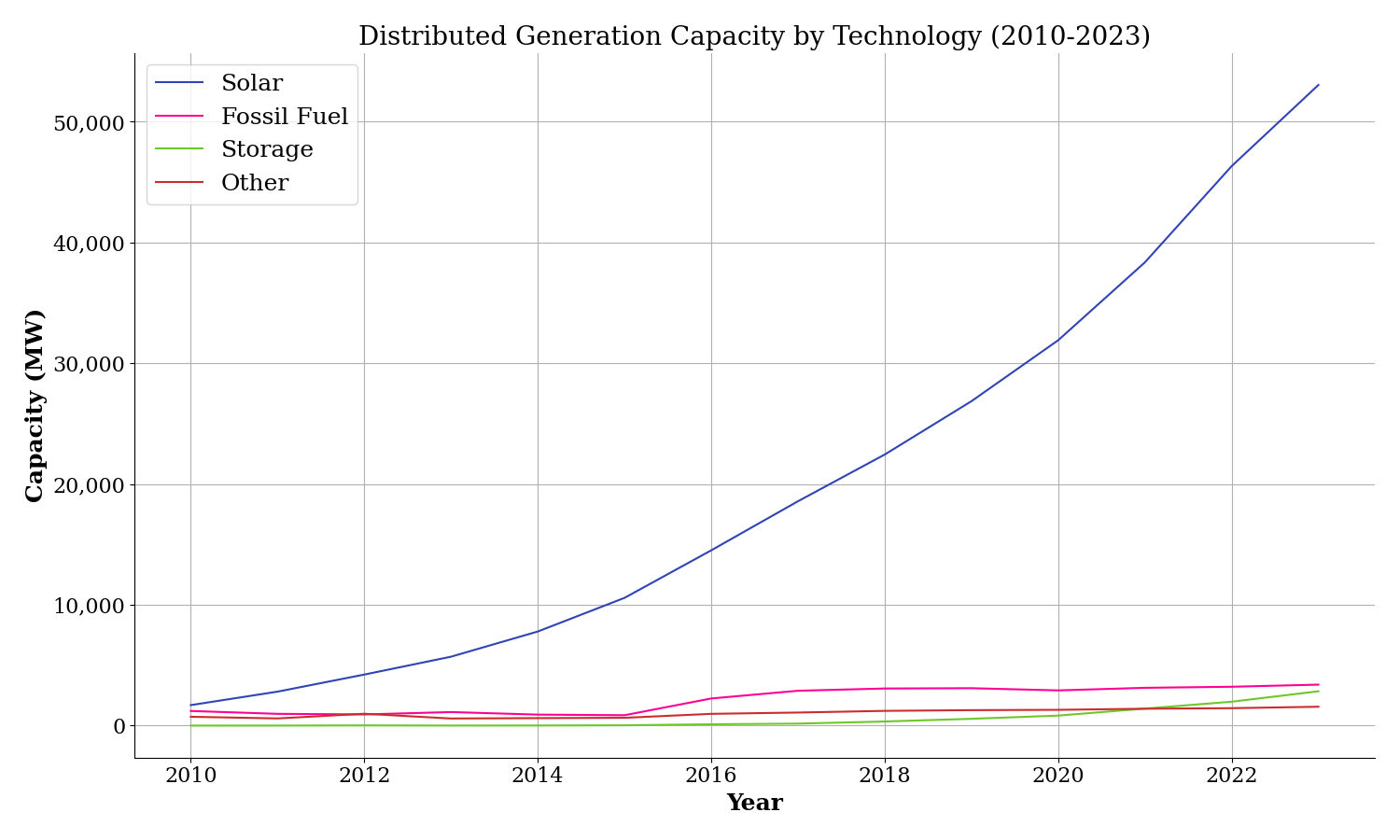

The first benefit which DERs provide by their very definition is local control. Assets like rooftop solar systems, backup batteries, and microgrids are distributed on the grid, so they can be owned and operated within the communities where energy is needed. Whether a given DER is clean depends on the type of DER, but clean solar photovoltaic (PV) generation is by far the leading source of distributed generation, with storage resources quickly growing into second place.

Access to clean energy is critical due to the generational harm caused by air pollution from power plants which is over-concentrated in historically marginalized communities. When configured as part of a virtual power plant, DERs can even be used to defer or eliminate the need for expensive, polluting infrastructure.

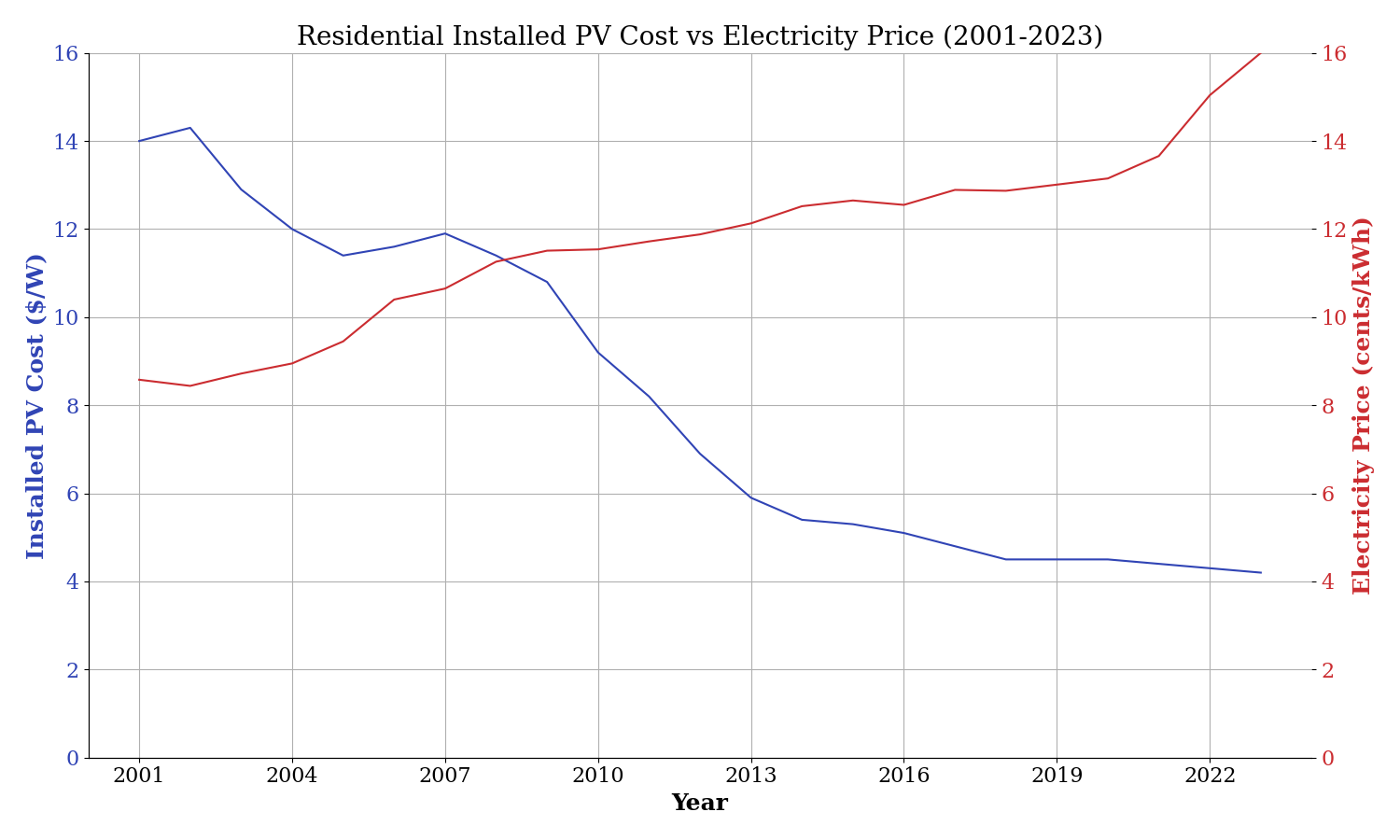

The rapid growth in solar capacity is largely driven by the falling cost of solar PV systems, meaning that DERs are an affordable source of energy. The figure below shows how the installed cost of residential solar PV systems has been falling steadily since 2001, while the price of residential electricity has been rising steadily. This trend is expected to continue, with NREL estimating that the cost will drop below $2 per watt by 2032. Meanwhile, the US Energy Information Agency predicts that electricity costs from the grid will continue rising with inflation.

How distributed energy resources support a resilient grid

DERs can also contribute to a resilient and reliable energy system, but it’s a bit more complicated. Solar PV systems are typically connected to the grid through grid-tied (or grid-following) inverters that are configured to automatically stop producing power whenever they detect a disturbance or outage on the grid. This is done for a number of technical and safety reasons, and historically, the range of disturbances that these inverters could “ride through” was very narrow. This means that many DERs neither improve nor reduce the grid’s reliability and resilience directly, as they are programmed to disconnect during grid disturbances. However, this is beginning to change, and there are several other ways in which the addition of DERs can enhance both reliability and resilience of the grid, often at a lower cost than “traditional” solutions.

First, new standards are being implemented that require conventional inverters to ride through a broader range of grid disturbances, supporting a more resilient grid. And research indicates that battery energy storage systems with grid forming inverters (which can produce power during an even wider range of grid disturbances) can support a more resilient grid, especially as the overall share of renewables increases.

Second, as discussed in previous posts in this series, DERs can be configured as part of microgrids or virtual power plants (VPP) to enhance resilience; microgrids directly provide resilience to the buildings and homes that are in the microgrid, while VPPs have the flexibility to be dispatched in multiple ways that support grid resilience and reliability, such as shifting power flows to reduce outages during extreme weather. VPPs managed with a DERMS (DER management system) give utilities the ability to closely monitor and control DERs and can be used to further enhance resilience.

Finally, UCS research indicates that across the grid at large, renewables are more reliable than fossil plants.

Energy justice requires making distributed energy resources more accessible

We’ve seen how DERs can support energy justice by providing clean, affordable, reliable energy that’s locally controlled. This brings us to the final dimension that energy justice requires: DERs must be accessible to the communities that need them. But what does “accessible” mean? This refers to more than just whether DERs are in stock and available for purchase; it also depends on whether there are clear pathways to install DERs in communities where energy justice is lacking, or whether there are significant barriers.

As it turns out, significant barriers remain. Like the roots of inequity itself, many of these barriers are systemic. A 2023 report from NREL organizes these barriers into three categories: cost-based, socioeconomic, and historical. (The report focuses on barriers to VPPs, but many of these also apply to DERs as the underlying technology that VPPs are built on.)

Cost-based barriers include lack of access to capital and challenges to securing loans. While DERs provide more affordable electricity, acquiring them is a barrier to entry for those who do not have the means to purchase them outright, or who do not qualify for loans or other financing approaches. Lack of capital is a result of the wealth gap between white and BIPOC households in the United States, which is widely-attributed to discrimination and systemic racism.

These cost-based barriers extend to housing quality and access as well. Due to high housing costs and historic redlining, Black and Latine households are more likely to be renters in the United States, and thus have significantly reduced access to DERs which typically must be purchased and installed by the homeowner. Further, when BIPOC and low-income residents do own their homes, the homes are more likely to be older and in need of repairs or upgrades before DER installation would be practical or feasible.

The need for upgrades and repairs also extends beyond the homes themselves to the very grids that homes are connected to in historically disadvantaged communities. Recent research in Ohio found that these communities are more likely to have older electrical infrastructure and less grid capacity available to add DERs such as solar and storage.

Socioeconomic barriers include differences in how underserved communities use energy compared to “typical” DER users, who often have higher and stable incomes, and limited freedom of choice (which many underserved households experience) to be able to take full advantage of the potential of DERs.

Historical barriers include mistrust between communities and utilities, and failure on the part of utilities and DER companies to effectively communicate with and engage communities. This mistrust is driven by exclusion from decision-making, unfulfilled promises around cost savings, and a legacy of utilities building polluting infrastructure in or near neighborhoods without community input.

Industry structure is a barrier to accessibility

A final barrier to DERs in BIPOC and low income communities is baked into the structure of the utility industry itself, as explained in a 2022 article in Stanford Technology Law Review. The article walks through the history of the US electric utility industry, detailing how we arrived at a situation where nearly three-quarters of Americans are supplied with power by a small number of regulated for-profit, monopoly, investor-owned utilities (IOUs). IOUs generate profits by investing in their own infrastructure and putting pressure on regulators and legislators to maintain the status quo.

The growth of DERs represents a significant change to the industry and is perceived by many IOUs as a direct threat to their profits. The article details several examples of utilities successfully arguing that the definition of a “utility” in certain states includes the owners and operators of DERs, creating significant barriers for those seeking to install DERs.

Community microgrids represent an even greater threat to the utility business model, giving communities the power to build and operate their own electrical infrastructure within a utility’s exclusive territory. While the right of for-profit utilities to exist is enshrined in law, no state currently allows community microgrids to freely enter the market, though California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Puerto Rico are taking steps in that direction.

Building a distributed grid that delivers energy justice

Despite these challenges, there are a number of solutions available to address the lack of accessibility and leverage DERs for achieving energy justice. DER programs can provide dedicated funding and loan structures for low-income households. Affordable housing programs can include DERs and VPP enrollment in subsidized housing costs. Overcoming socioeconomic and historical barriers is more challenging for an industry that has historically ignored BIPOC and low-income communities, but numerous resources exist for pivoting to energy justice and building a system that serves all, regardless of their race, income, where they live, or any other factor.

DERs are more than just new technologies—they are a means to transform the grid from a system rooted in inequality to one that centers energy justice. But achieving this requires more than just technological innovation. It will require utilities, regulators, policymakers, and advocates to work together with BIPOC and low-income communities. We must center community voices, redesign programs and incentives with equity at the core, and disrupt outdated utility structures that protect monopoly power over public benefit. The birth of the grid was marked by rapid change and technological innovation. Let’s make sure its rebirth is rooted in a radical centering of wellbeing for all; energy justice demands that we leave no one behind.