California has proposed repealing its recent regulation on in-use emissions from locomotives, another major step backwards in the fight against freight pollution. The landmark regulation would have helped move the railroad industry away from diesel to electrification, like the vast majority of the global rail industry, and ensured in the interim that rail companies reduce pollution from their current locomotive fleets.

The rail industry has stymied progress in reducing emissions over the past decade, in spite of federal rules meant to clean up the sector due to the disproportionate impacts caused by the diesel-powered locomotives. Below, I walk through the harm this has on local communities, why it’s happening, and why we need a strong national rule to coerce this dirty industry into cleaning up its act.

Railroads: Profits for me, pollution for thee

Just like the ol’ robber baron heyday of the late 19th century, 21st century railroads are raking in the money, though now those incredibly high profit margins (at nearly 25 percent, roughly 3 times the market average) come from moving goods instead of people.

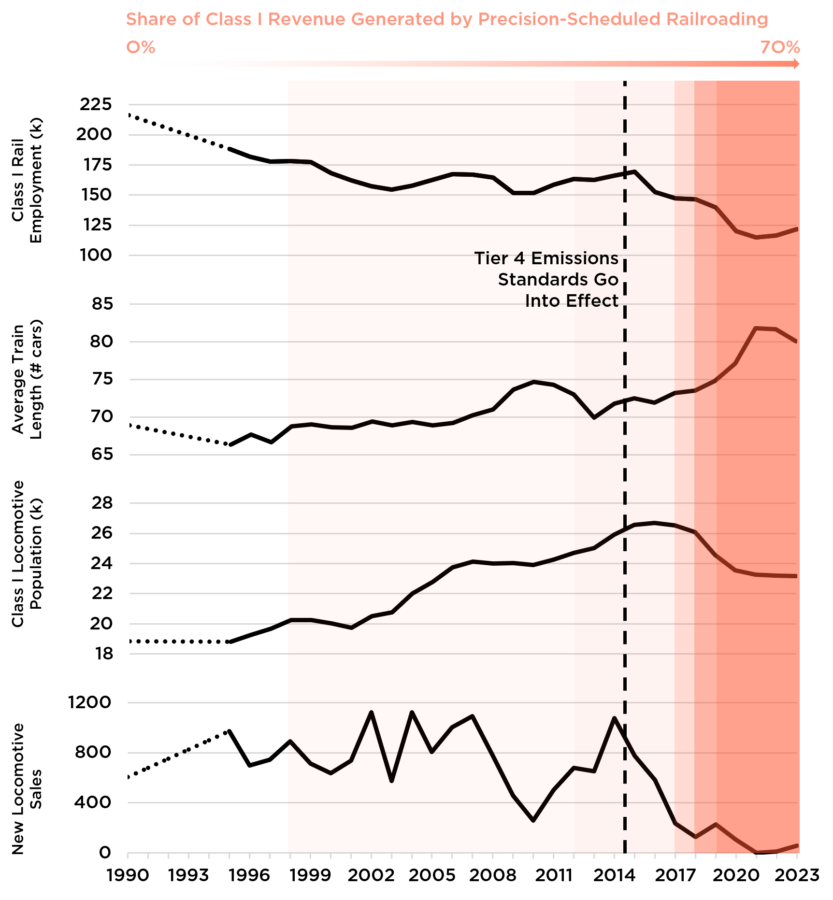

Over the past two decades, the profit margins for the railroad industry have skyrocketed as the result of a new operational strategy called Precision-Scheduled Railroading (PSR). While exactly how this is implemented can vary from railroad to railroad, the primary metric by which PSR is measured is the operating ratio, the ratio of operating expenses to operating revenue. The goal of PSR is to minimize the operating ratio. PSR was first implemented by Canadian National in 1998, which represented less than 5 percent of Class I railroad freight revenues. However, a rapid adoption by three major railroads caused the share of Class I railroad revenue from PSR-utilizing firms to increase from less than 7 percent in 2016 to 70 percent by 2019, where it remains today (privately owned BNSF is the only Class I carrier not yet to adopt PSR).

The widespread adoption of PSR has had significant impacts on the railroad industry overall. According to a report from the Government Accountability Office, there are three consistent factors in the implementation of PSR: 1) cutting workers to reduce operating costs, something that has come under scrutiny recently in the wake of the East Palestine derailment; 2) increased train lengths, which itself can lead to its own safety issues; and 3) a reduction in assets, including locomotives.

Those impacts are clear when looking at the data. Employment in the rail industry is about two-thirds of what it was prior to the start of PSR implementation. The average train length has shifted from under 67 cars to 80 cars, a 17 percent increase. Freight volumes have increased by just 10 percent in that time, which leads to fewer active locomotives, as can be seen in the rapid and recent reduction in the locomotive population.

Because railroads need fewer locomotives, this has caused a glut of locomotive availability. Not only does this reduce sales of new locomotives, but it makes it easier for railroads to resuscitate aging locomotives that previously would have been replaced.

We can rebuild it—we have the technology (and lax regulations)

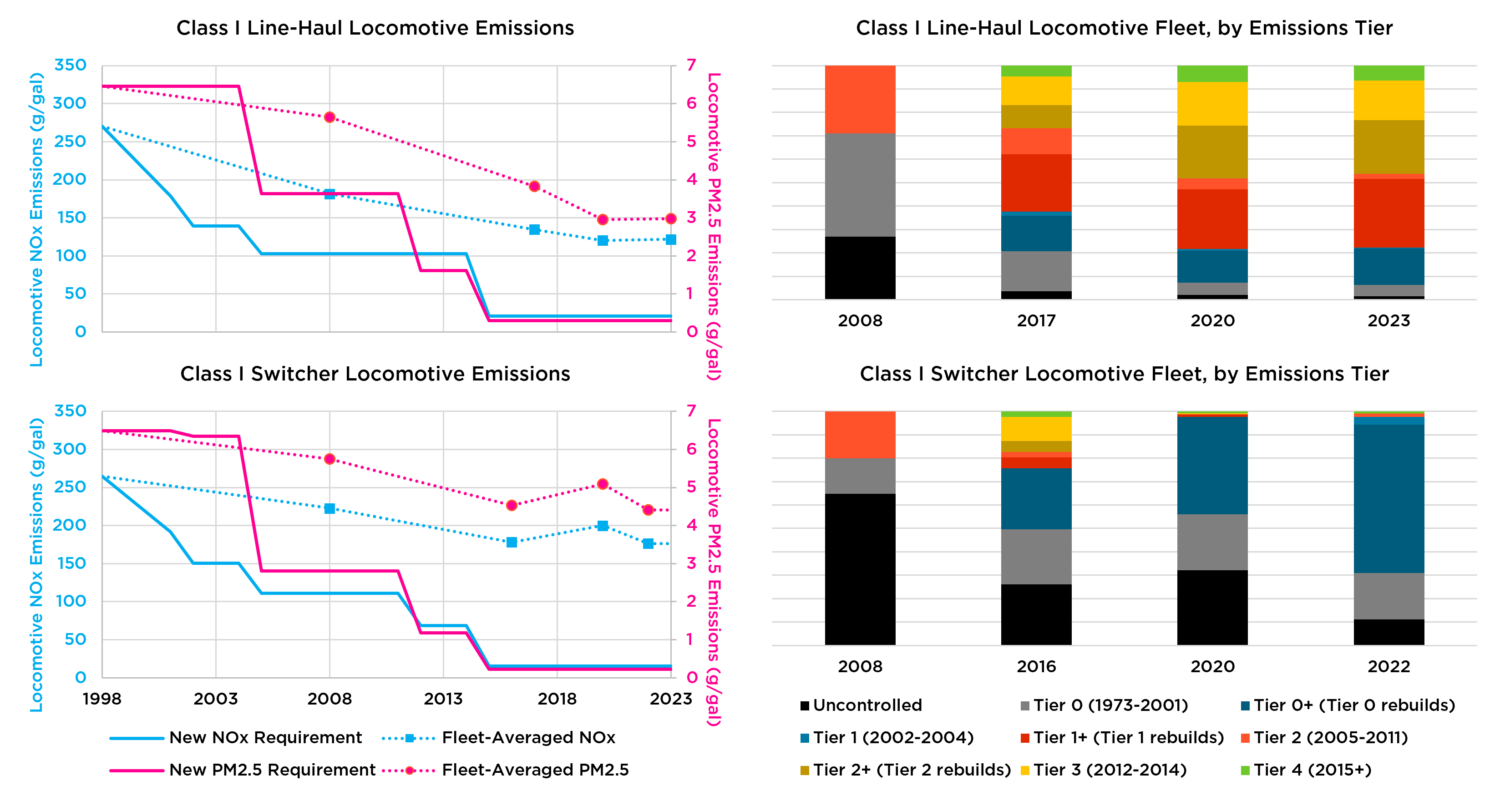

Under the Clean Air Act, the Environmental Protection Agency sets emissions standards for engines in new locomotives. Each successively more stringent standard is defined as a particular “tier,” with today’s new engines currently required to meet Tier 4 emissions standards. The agency is also responsible for defining what it means for a locomotive to be “new.” It is a bit like the famous ship of Theseus–at what point does replacing individual pieces of a ship (or any object) constitute making an entirely different ship (object)?

This is particularly important when it comes to diesel-powered locomotives, which pull 100 percent of all freight rail in the U.S. These locomotives are powered by a diesel engine connected to an electric generator. That electricity is then used to power traction motors that drive the wheels. Now, it may be that components of the locomotive need to be replaced, either for maintenance or upgrades. It is common, for example, to rebuild a diesel engine by taking it apart, replacing any worn or damaged pieces, and putting it back together. EPA rules define at what point in this replacement or maintenance process the engine may be considered newly manufactured (versus remanufactured), and therefore at which point newer, more stringent rules would apply. If a rebuilt engine does not meet the threshold to be considered newly manufactured, the engine may have to meet additional requirements to ensure that the emissions controls operate at least as strong as the engine when it was first built.

With a glut of locomotive engines available, there is no shortage of old locomotives to be rebuilt or scavenged for spare parts. Just look at this “helpful” how-to article on how to save money and avoid those pesky, life-saving regulations while “supporting the return on asset goals of today’s PSR business model.”

Predictably, the impact of this business practice has been to forestall adoption of newer and better performing (from an emissions perspective) locomotive engines. Emissions improvements from the locomotive fleet have effectively stalled.

Prior to 2015, when Tier 4 standards were introduced, locomotive sales averaged just under 800 new locomotives per year. Sales have now slowed such that the total sales since 2017 are just over 800 new locomotives—in other words, it’s taken 8 years to match what used to be sold in a single year. Had the market continued on its historical pace, there should be close to 7,000 Tier 4 locomotives in the fleet—instead, there’s just 1,400. The direct result of this reduction in sales is a locomotive fleet emitting over 20 percent more pollution than it would have under the status quo deployment anticipated by EPA.

Moving the United States beyond diesel, like the rest of the world

Locomotive engines certified to Tier 4 emissions standards are the cleanest diesel-powered trains in the United States today, and if deployed nationwide would cut smog-forming NOx emissions from the line-haul locomotive fleet by 83 percent and health-harming PM2.5 emissions by nearly 90 percent. For the switcher fleet operating in railyards, which tend to be in densely populated areas, deploying Tier 4 locomotives could cut NOx and PM2.5 emissions by 95 and 91 percent, respectively, compared to the status quo.

The process to replace our nation’s outdated diesel locomotives should already be well underway, but railroad behavior has limited turnover. But if we need to replace the fleet, which is capital intensive, why do so with a partial solution when the rest of the world has solved the problem entirely? We should be electrifying the rail industry like everywhere else and eliminate entirely the local emissions associated with locomotives.

There are a number of strategies to electrify locomotives. The most widely adopted technology is catenary locomotives, which are already used around the world: in Russia, on the Trans-Siberian Railway, spanning nearly 6,000 miles; in Europe, with more than 80,000 miles of electrified rail, including much of the Trans-European Transport Network and its dedicated freight corridors; in India, on freight routes like the Eastern and Western Freight Corridors which can handle double-stacked freight; and in China, with a rapid expansion of thousands of miles of freight rail, including the lengthy trade route with Europe.

Ongoing developments in battery technologies have enabled the development of discontinuous catenary rail, where the train can be powered by a battery in areas where catenary is not available, whether that is because of as-yet-unconstructed power lines or in tunnels or other infrastructure where it may be expensive to deploy. One recent study highlighted in a recent report of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) found that discontinuous catenary rail could cut the capital costs of electrifying the studied rail corridor by 67 percent! This is part of the reason the joint action plan from the Department of Energy highlights discontinuous catenary as the #1 strategy around which to plan decarbonization of the rail sector.

Catenary and discontinuous catenary rail are not the only electrification strategies capable of meeting the needs of the freight rail industry, however: battery-electric locomotives are technologically capable of line-haul operation as the sole power unit as well. Additionally, they can also be phased into a manufacturers fleet in hybrid configurations with current diesel-electric locomotives, allowing for immediate fuel and emissions reductions as part of a holistic and swift transition to zero emissions rail.

While the FRA identified the promise of freight rail electrification, the American Association of Railroads, the industry’s trade group, pushed back with inflated costs and can’t-do attitude, a symbol of the continued obstinance of the industry when it comes to cutting locomotive emissions.

Regulators to the rescue?

With sales of new locomotives at historic lows and locomotive operators sidestepping emissions improvements through rebuilt diesel engines, it’s clear that the current approach to regulating emissions from rail has massive gaps.

To patch these gaping holes and adequately protect communities, regulators cannot let railroads engage in an infinite loop of rebuild and pollute. There are a number of regulatory strategies that can be used to reduce locomotive emissions and address the status quo:

- reducing the threshold below which rebuilding the engine constitutes a newly manufactured engine and/or eliminating disparities in emissions standards for rebuilt and newly manufactured engines to shift the economic case against extending the lifetime of older, dirtier diesel engines;

- updating requirements for rebuilt engines so that they are more in-line with the best available technologies of today, rather than when they were originally manufactured;

- setting fleet requirements to ensure continued progress on reducing emissions;

- and/or requiring the deployment of zero-emission locomotives to eliminate local rail pollution entirely.

In 2022, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) finalized a rule that would do all of these things—it required (beyond 2030) all new and remanufactured locomotives to meet Tier 4 standards, regardless of build date; it set fleet-average requirements to ensure that any railroad operating in the state meet minimum standards for pollution from their entire operating locomotive fleet; and, most importantly, it required steady progress towards eliminating emissions entirely from railroads operating in the state.

This rule was fought tooth and nail by the American Association of Railroads, the main trade group for the freight rail industry. Not only did they lobby hard against the regulation, but they even sued CARB over the lifesaving rule.

Unfortunately, CARB likely needs authorization from the EPA to enforce these standards, which is granted following the agency’s request for a waiver of pre-emption under the Clean Air Act. Unfortunately, the Biden administration did not grant such a waiver before leaving office. As a result, CARB withdrew its request for authorization and is now, to avoid any uncertainty about the program’s status, proposing to repeal this landmark regulation.

The continued lack of federal action on rail is killing people

The docket for the CARB regulation makes clear the tremendous air quality and health benefits the In-Use Locomotive regulation could have made to Californians, if enforced, including a 67 percent decrease in particulate matter emissions and 55 percent reduction in smog-forming NOx emissions from the rail sector in California by 2030. Unfortunately, instead it will go down as a missed opportunity thanks to a lack of federal action on CARB’s request.

But it isn’t just the waiver request where the federal government has been missing in action. The most recent set of national locomotive engine standards were finalized nearly two decades ago, in June 2008, by EPA and left a massive loophole that industry has exploited to virtually nullify most of the requirements of the rule by repowering old locomotives indefinitely using outdated technology instead of replacing them with the lowest-emitting solutions available. Since finalizing that rule, the only action to clean up pollution of rail from the agency has been to empower states to set the very rules for which the Biden administration then neglected to provide a waiver.

EPA affirmed the basis for California’s regulation, noting “the large share of older locomotives in the Class I, II, and III railroad fleets and their emissions[‘] contribution to ambient concentrations of air pollution that may violate the ozone and particulate matter [air quality standards].” But it is not enough for the agency to point out the harm—EPA must redress that harm.

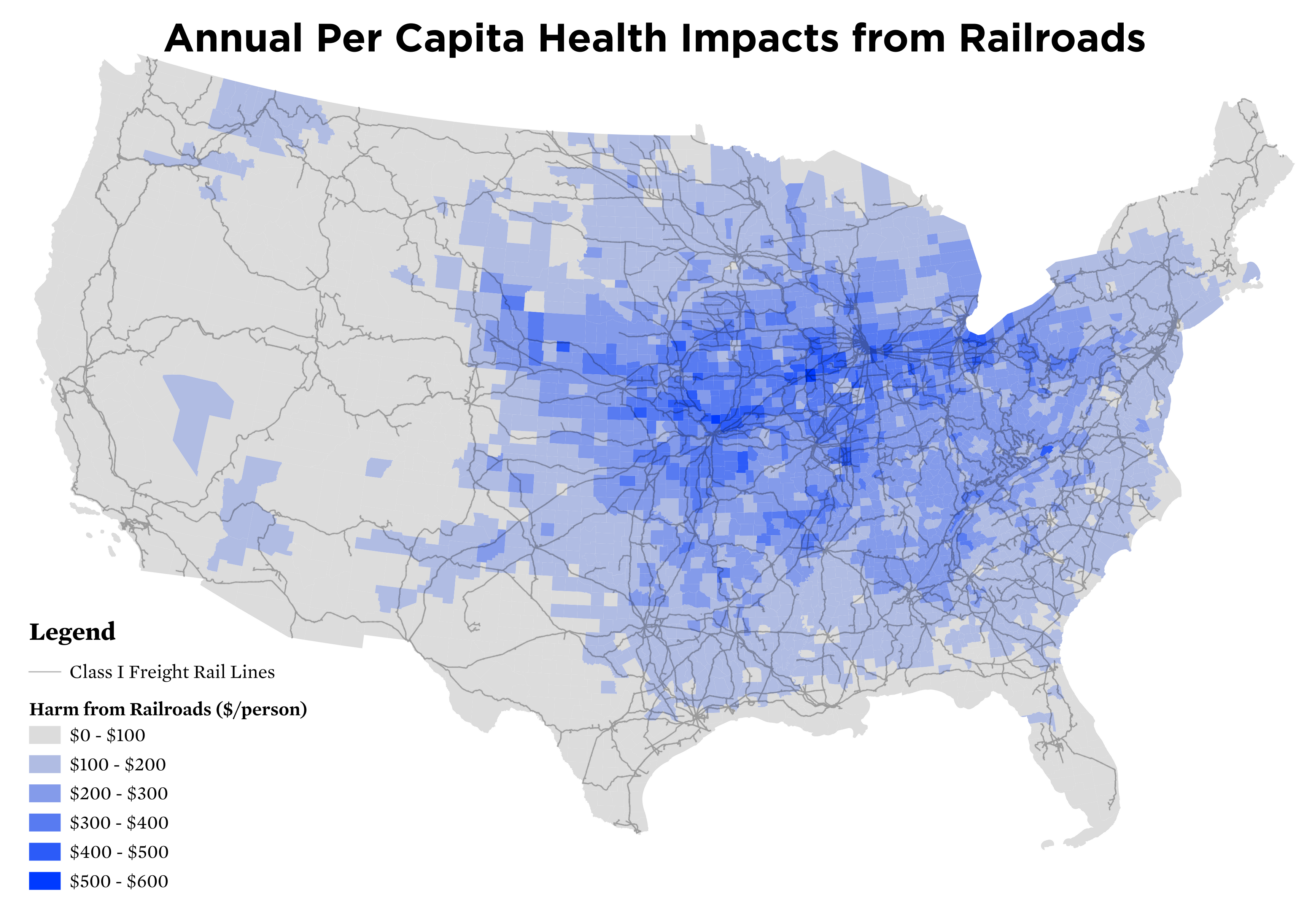

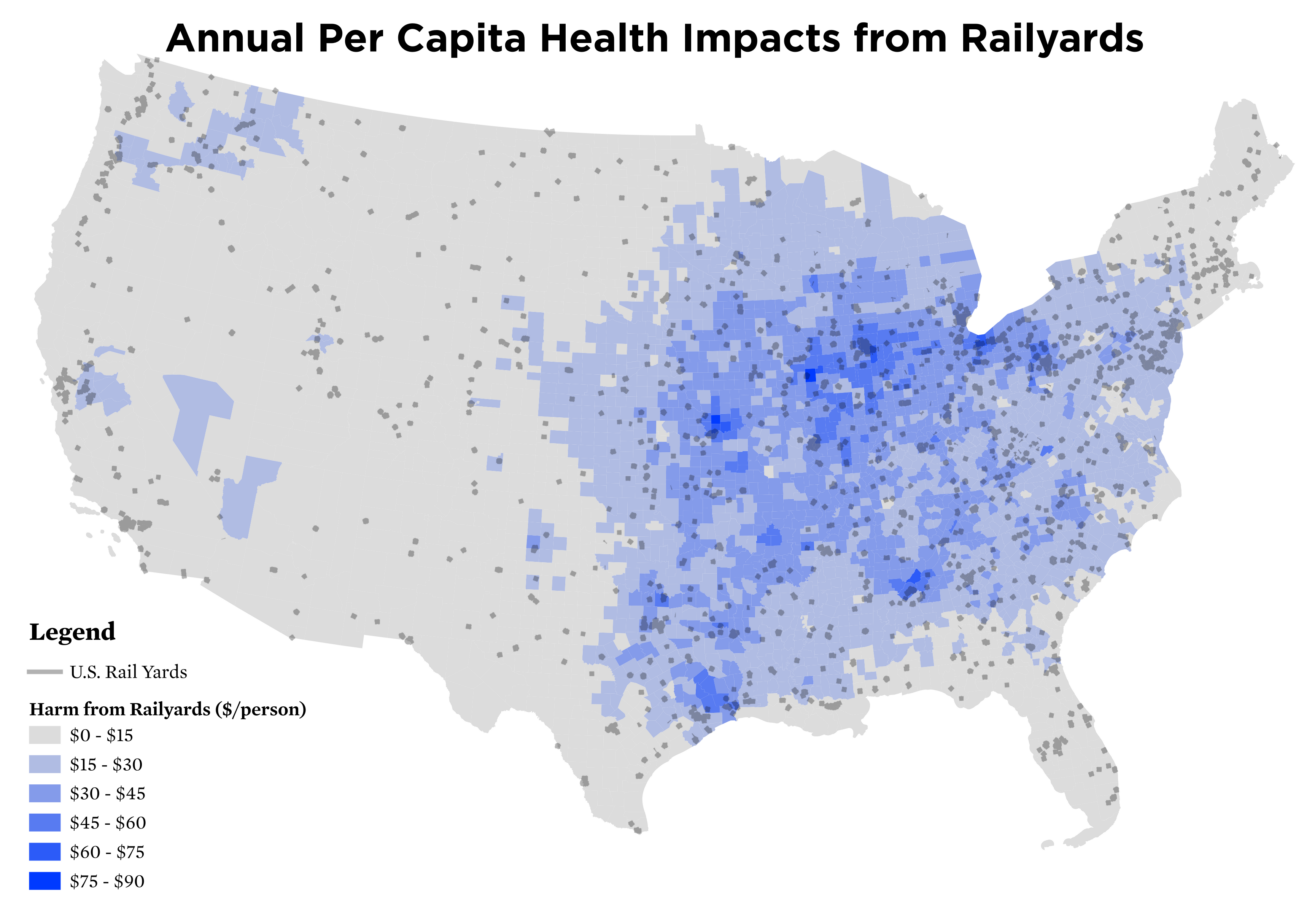

According to EPA’s COBRA model, it is estimated that the rail industry is responsible for between 2,200 and 3,100 premature deaths annually, with total health-related costs of $36 to $48 billion. The vast majority of this harm comes from freight rail: the six Class I railroads are responsible for between 86 and 91 percent of all rail pollution, according to EPA analysis.

Government must intervene to protect the public from the rail industry

The impacts of freight rail pollution are not uniform—despite representing just 5 percent of total fuel consumption from rail, Class I switchers represent 15 to 20 percent of the total health impacts of the entire rail sector, owing both to their proximity to population centers and them being older and more highly polluting than Class I line-haul locomotives, which consume the vast majority of diesel fuel used in rail.

The rail industry has failed to clean up its emissions, choosing to prioritize profit margins over modernizing its fleet. Those margins come on the backs of communities bearing the brunt of the pollution from this sector, resulting in premature death, asthma, hospitalization, lost school and work days, and so much more.

Government at all levels has neglected to address these emissions. The federal government has failed to strengthen its lax regulations and has even stymied state efforts to address the issue. States and localities have failed to put forth robust solutions commensurate with the scale of the problem.

The case for rail electrification is clear in the benefits to the economy, public health, and the environment. But decisionmakers at all levels of government are needed to combat the entrenched interests of multibillion-dollar industry whose profits are built on ignoring the direct harms of their industry. Government must intervene immediately to set the rail sector on a path to zero emissions freight, or railroad companies will continue to endanger communities nationwide.