In 2010, a derelict sailboat called the Golden Rule was hauled from the depths of Humboldt Bay, California, where it had sunk. Keen eyes recognized that this boat had a notable history as a catalyst for anti-nuclear activism and, before long, a group called Veterans for Peace was overseeing its restoration. Its salvation was a prescient act because the boat’s story is not done being told.

I was fortunate to be invited aboard the boat on its recent return from San Francisco to Eureka as a crew member, following in the footsteps of its original crew, and reflecting on how its mission to raise awareness of the threat of nuclear weapons remains as relevant today as when the boat originally sailed.

In 1958, a group of four Quaker pacifists purchased the Golden Rule and set out to place themselves in a US nuclear test zone that was then active at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The crew was led by Albert Bigelow, a former World War II naval commander who would also later take part in the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Rides.

At the time of the original voyage, the risks of aboveground testing were entering public conversation. Prominent figures including Linus Pauling, Albert Schweitzer, Bertrand Russell, and Albert Einstein were speaking out on the biological and existential risks of nuclear weapons, and concern over the ubiquity of nuclear fallout was generating public fear. As Quakers, Bigelow and his crew felt a moral duty to intervene.

They made it as far as Honolulu before the Atomic Energy Commission issued a hasty decree that banned navigation in the test area, resulting in their arrest and imprisonment. The Golden Rule never reached Eniwetok, but news of the crew’s plight did reach the mainland and helped spur a popular anti-nuclear protest movement—one that borrowed from the nonviolent action and protests that were then defining the civil rights movement. The legacy of the Golden Rule’s message would carry on long after the voyage.

As we set out under the Golden Gate Bridge on a much less momentous voyage up the coast, we were surrounded by whales and seabirds. We turned northwest under a setting sun and watched the Point Reyes lighthouse illuminate to help guide us. Someone quipped that the Pacific Ocean was living up to its name with unusually calm conditions. Amidst the rich sea life around us, it was hard to imagine some of the largest nuclear weapons in history vaporizing distant parts of this same ocean in complete and utter contradiction to the peaceful evening we were experiencing. What feels abstract today were immediate realities for Bigelow and his crew, which caused me to reflect on their motivation and what motivates people to action today when popular awareness of nuclear issues is weak, despite renewed emphasis on nuclear weapons production and deployment.

Although aboveground and atmospheric testing did cease with the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, underground testing continued until the 1990s when the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) was adopted (but which the United States has never ratified). India, North Korea, and Pakistan are the only nations to have tested since then. While nuclear testing may seem like an artifact of the past, some advisors to the current administration are advocating for its resumption, a move that has already generated bipartisan opposition in Nevada, where any new tests would likely occur. Despite these new developments, most of the public remains unaware, indifferent, or perhaps overwhelmed by other existential crises that fill today’s headlines.

Bigelow’s motivation to act against testing was personal. As a naval commander in World War II, he was aboard his ship in the Pacific when he learned of the bombing of Hiroshima. After becoming a Quaker, he would later host some of the “Hiroshima maidens“—young Japanese women left disfigured by the atomic bombing—in his home. They were brought to the United States to undergo plastic surgery in an attempt to help them avoid the stigma then associated with being hibakusha (a bombing survivor). While the program has been the subject of intense controversy, Bigelow credited the women’s lack of animosity toward Americans as influential in his feelings about America’s use of the atomic bomb. He resigned his naval commission one month before becoming eligible for his pension.

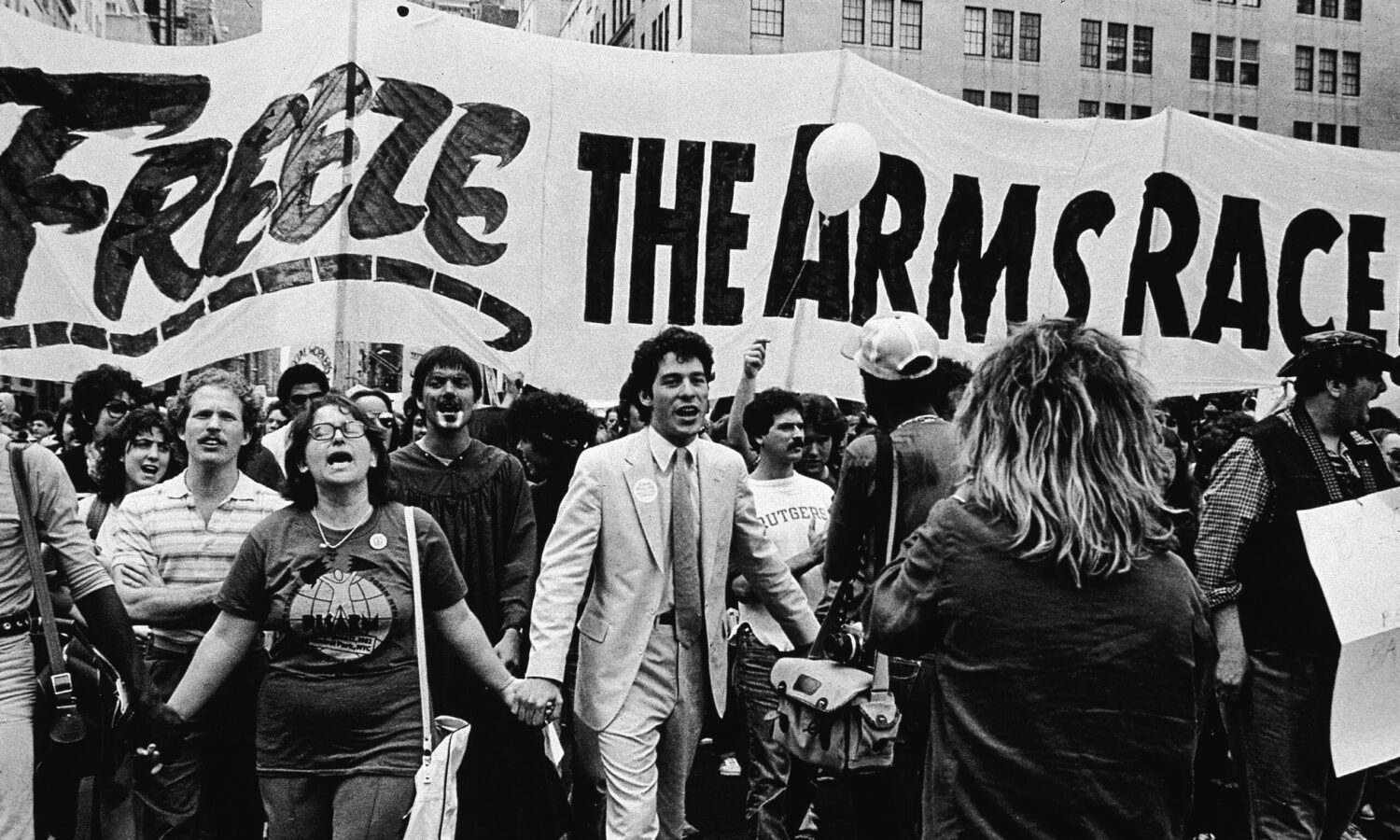

Bigelow was known to lament that the original voyage of the Golden Rule fell short of its intent because it did not reach the testing grounds (although another boat, the Phoenix of Hiroshima, did carry on its voyage). Historians might beg to differ. The Golden Rule became a symbol of anti-nuclear resistance and helped spur what eventually led to a broader anti-nuclear movement. The Golden Rule and its crew are directly credited with inspiring the first Greenpeace voyage aboard the Phyllis Cormack to protest nuclear testing in the Aleutian Islands and many cite the Golden Rule in helping sow the seeds of what would later grow into the nuclear freeze movement of the early 1980s.

Tensions with the Soviet Union were growing in the early 1980s and the Reagan administration’s pursuit of space-based defense systems (coined “Star Wars“) became a new target for public opposition. In 1981, the Union of Concerned Scientists held teach-ins at 150 schools while other organizations circulated petitions and rallied public support. In 1982, the UN’s Second Special Session on Disarmament was held in New York and was greeted by a million protesters in Central Park—believed to be the largest peace rally in US history. Professional organizations, worker unions, and religious groups united in support of a nuclear “freeze,” and nine states, 275 city governments, and 446 town hall meetings passed pro-freeze resolutions in 1982 with roughly 60% popular support nationwide. International movements, including the Appeal for European Nuclear Disarmament (END), added momentum abroad.

As I sat on my first night watch, the sky was completely clear and the new moon had set, leaving an amazing view of the stars and Milky Way, which was luminous all the way down to the horizon. Bioluminescent algae were twinkling in the Golden Rule’s wake, seemingly connecting with the stars above. Across the dark skies, satellites were visible to the naked eye, streaking overhead against the background of stars. I couldn’t help but think of the parallels between Reagan’s Star Wars and the current administration’s proposals to weaponize space.

The contrast between the stark beauty of the night and the concept of militarizing it was jarring. While some of those satellites were guiding our GPS navigation, others were relaying terabytes of disinformation designed to polarize and divide those back on land. Steering the boat into the handle of the Big Dipper as it set in front of us, I relished the fact that my phone was far beyond reception, placing me literally and figuratively miles away from the quotidian noise as the Golden Rule glided over the dark water.

Left to my thoughts, I wondered how a modern anti-nuclear movement may take hold. What will be required to motivate the public when the modern cacophony of threats seems to overshadow nuclear weapons, despite the fact that they could become an existential priority within minutes under the current US nuclear posture? Bigelow wrote, “How do you reach men when all the horror is in the fact that they feel no horror? It requires, we believe, the kind of effort and sacrifice that we now undertake.” Who will be the next Albert Bigelow, or what can succeed the Golden Rule in the public consciousness?

It is clear that although the original crew of the Golden Rule succeeded in motivating awareness of nuclear testing and the threat those weapons posed, that awareness waned along with global nuclear arsenals in the wake of the Cold War. Today’s nuclear landscape shares many worrying parallels with the Cold War surge in arms and rhetoric. This comes against a backdrop that includes additional nuclear-armed states and added risks from emerging technology.

Paradoxically, the resurgence of threat may be the catalyst for renewed recognition and resistance. The 2024 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Japanese organization Nihon Hidankyo in recognition of its efforts to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons. In 2017 Pope Francis declared the possession of nuclear weapons to be immoral, establishing the position of the Catholic Church. In 2021, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons entered into force, which upholds a blanket ban on “developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons.” There is hope, perhaps, that a new anti-nuclear movement can borrow from climate action and nonviolent social justice movements that are gaining traction with younger activists. The Golden Rule and the Union of Concerned Scientists both have a role to play in providing the education required to bring that about.

As we carried on past dawn, dolphins swam alongside the Golden Rule, seemingly encouraging it onwards. Perhaps they also know that the boat needs to carry on. What the Golden Rule symbolizes is as relevant today as in 1958 when Bigelow and his crew set out from California for the first time. Despite the contrast of this trip from my usual work, I stepped off the boat in Eureka with a new sense of urgency—a deep reminder that we cannot give up and that there is work yet to do.

“When you see something horrible happening, your instinct is to do something about it. You can freeze in fearful apathy or you can even talk yourself into saying that it isn’t horrible. I can’t do that. I have to act. This is too horrible. We know it. Let’s all act.”

—Albert Bigelow, The Voyage of the Golden Rule: An Experiment with the Truth, 1959