This winter has been hitting hard across the United States, as many can attest firsthand. In New England, where I live, temperatures in the single-digits—and at times dipping below zero—caused energy demand to soar. And that, in turn, has led to some serious air pollution from local oil-fired power plants.

Given New England’s abundant clean energy resources, it doesn’t have to be that way. New analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) underscores the potential of offshore wind to bolster winter reliability. And the numbers are just the latest strong vote in favor of standing up that offshore wind power in a serious way, and soon.

Winter Storm Fern comes

When Winter Storm Fern swept across the country around the weekend of January 24-25, 2026, it brought with it arctic temperatures. In New England, temperatures dropped below freezing (and, as of this writing, more than a week later, haven’t made it back up in the Boston area).

Under conditions like that, the energy scene in New England follows a familiar pattern, and it stayed true to form during the recent storm:

- The low temperatures drove up demand for heating in homes and businesses. In New England, pipeline gas for furnaces and boilers accounts for the largest share of home heating (40% of households).

- The storm also drove up demand for electricity, including to drive the pumps and fans associated with those furnaces and boilers, as well as to power electric heat (electric baseboards and, increasingly, heat pumps). New England is a heavy user of gas for electricity too, with that fuel accounting for more than half of in-region electricity generation.

- That overreliance on gas put the power sector’s fuel appetite on a collision course with demand from the gas distribution companies that serve New England’s homes and businesses. Because gas companies contract for that gas far ahead of time, while gas power plants look to buy gas only as they need it, when push comes to shove, the power plants lose out.

- The lack of gas pushed grid operator ISO New England (ISO-NE) to “Plan B.” Many of the gas power plants in the region have dual-fuel capabilities, the ability to burn oil instead of gas. Gas is not a clean option for electricity generation, but oil is even dirtier, in terms of both carbon pollution and emissions of pollutants such as particulate matter (i.e. soot) and sulfur dioxide (SO2). The fuel is dirty enough that, a generation ago, communities fought protracted—but ultimately successful—battles to rein in pollution when oil is burned. To meet the critical need for power during this cold snap, however, ISO-NE sought, and received, waivers on pollution limits from the Trump administration during Winter Storm Fern.

The result of the fallback to an even dirtier fuel, running with no pollution control equipment, was, to quote my colleague Susan Muller, “like an oil spill in the sky”. The lights stayed on, but at a high potential cost to public health.

That chain of events could easily have been much worse this time around. As UCS has detailed elsewhere, a similar winter storm eight years ago led to an emergency declaration by then-Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker because of the danger of oil not showing up in sufficient measure. The “Plan B” for reliability was in danger of failing. And “Plan C” in a case like that might feature rolling blackouts, which no one should have to face in such weather.

A much better plan for reliability

A familiar pattern, with familiar—and untenable—consequences. So how do we break free of that pattern?

Experience and data show that more pipelines are not the answer. Even gas-producing regions had trouble keeping gas power plants operating during Fern, as has happened in other winter storms, because of the many ways that electricity generation with gas fails in the cold. New England’s energy portfolio is also already way too concentrated on that one fuel, one that the region doesn’t produce and for which it is at the far, far end of the pipeline.

A better plan is to draw much more on the resources that are already in the region, and that often get more abundant when we need them, not—like gas and oil—less abundant.

That’s where offshore wind comes in. Twenty years of data from ISO-NE show that, in most cold snaps, the same cold-weather systems that strain our grid have delivered large amounts of offshore wind energy to the region at the same time.

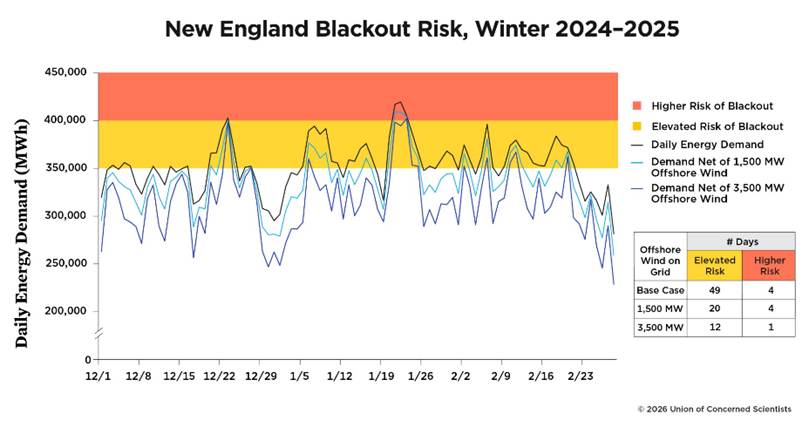

That’s also where the new UCS analysis comes in. It focuses on last winter (2024-25) in analyzing offshore wind power’s potential contribution to electricity reliability. It starts with ISO-NE’s own framework for assessing the risk of an “energy shortfall,” when energy supply falls short of energy demand. On a weekly basis in the winter, ISO-NE considers a large set of factors, on both the supply and the demand side, in order to determine when a shortfall is likely. One important risk factor is “daily energy demand,” which the ISO summarizes with a gauge graphic to illustrate increasing levels of risk. As shown in the graph below, last winter had plenty of days when electricity demand (the black line) was in the yellow elevated-risk zone, and some even in the orange higher-risk levels.

The analysis then uses hourly wind speed data offshore throughout the winter to calculate what wind turbines could have produced.

So how much could offshore wind have helped? The analysis assesses two levels of offshore wind capacity: 1,500 megawatts (MW), which is the total of the two projects under construction/almost completed that will feed power into the New England electric grid under contracts with utilities in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island; and 3,500 MW, which adds in the two other projects selected by Massachusetts and Rhode Island for the next round of contracts.

Even those levels of offshore wind would have made a real difference. The analysis found that 1,500 MW would have cut elevated demand-related risk by 55%, and 3,500 would have reduced it by 75%. That higher level would have kept demand out of the higher-risk zone on all but one day.

That would have meant many fewer days when the old pattern would have been followed, and a lot more days with greater reliability and lower pollution.

Keeping your lights on—without hurting your wallet

Keeping oil burners from firing up matters for more than just for avoiding oil-spill-in-the-sky phenomena, and the reliability challenges that lead to using oil-fired power plants more. Because oil is a really expensive way to generate electricity—even if gas becomes even more expensive at times like those—it also matters for our wallets. A study last year for RENEW Northeast showed that having 3,500 MW of offshore wind online could have saved New England ratepayers $400 million just in Winter 2024-25.

But reliability alone should be a powerful incentive to tear up the dogeared script that has, at times like these, tossed us from one fossil fuel to another. In the lead-up to this past weekend—days after Fern had swept through the region—ISO-NE was again warning of “tight operating conditions,” with peak daily energy demand solidly (and worryingly) in the orange “higher risk” zone, fuel supplies closer to red than green, and gas demand all the way on the red end.

There are all kinds of reasons why the move toward offshore wind makes sense, for New England and far beyond. And why poor policy decisions and still more delays—and the fossil-fueled disinformation that helps fuel those—are a disservice to all electricity users, airbreathers, billpayers, job-doers, and people-lovers.

This won’t be the last winter with extreme cold in New England. If the folks building offshore wind farms off our coast—the pile drivers, electricians, millwrights, pipefitters, ship crews, and so many others—are allowed to do their work, though, this may be the last one that we have to weather without a solid amount of offshore wind at our back.

We can’t change the weather, but we can change how we plan our power system to run smoothly through it all. In New England and beyond, offshore wind can be a central pillar of that plan.