When I lived in College Station, Texas, I kept dreaming about a Gulf Coast beach weekend escape from inland Texas. Even though this was early in the pandemic and the need for outdoor escapes was high, ultimately, I never made the trip. Honestly, I was kind of nervous about water quality. What’s the point of a beach adventure if you can’t even go into the ocean? In 2022, ninety of Texas’ beaches tested positive for unsafe levels of fecal bacteria (poop!), local advocates in Houston kept regular Poo Reports, and eventually, after having too many sewer overflows, Houston was ordered make $2 billion in wastewater infrastructure improvements. Upgrading infrastructure is expensive! This is why the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s historic investments provided a long overdue federal commitment to improving and protecting water quality (and why current threats to it and the agencies like EPA administering funds are so misguided).

Remember when swimmers were getting sick during the Paris Olympics from the Seine River? Fecal matter and other forms of harmful pollution enter our waterways from urban runoff, farmland runoff, and sewage overflows. Paris, like many coastal cities in the US such as San Francisco, has a combined sewer system where after heavy rain events, pipes get overwhelmed and raw sewage can flow into nearby waters. Challenges like this are about to get worse with the recent San Francisco v. EPA Supreme Court decision undermining the Clean Water Act and eroding the EPA’s ability to enforce it.

How does raw sewage end up in our oceans and rivers?

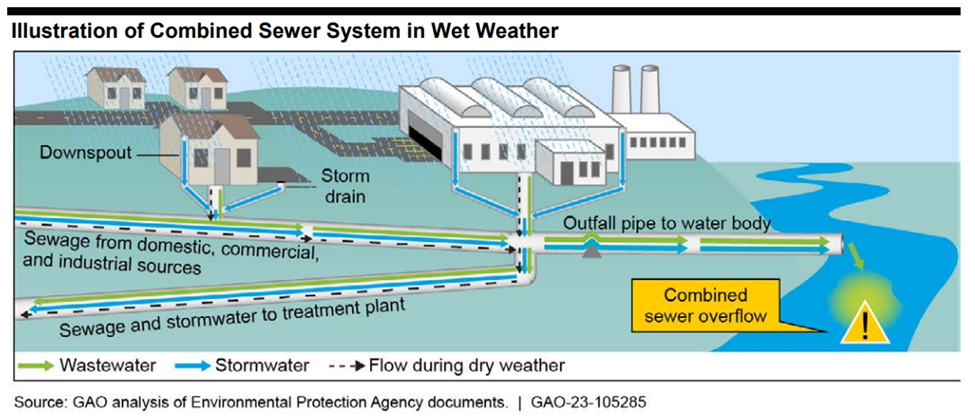

Across the country, more than 700 cities and communities have a combined sewer overflow (CSO) system, mostly in the northeast and around the Great Lakes—but also San Francisco. These older infrastructure systems combine wastewater and stormwater through the same pipes. In some cities, a combined sewer system means that usually both wastewater and stormwater get treated to the same high standards before releasing into the ocean. But when there are really heavy rain events, like atmospheric rivers, these systems often overflow untreated wastewater (raw sewage) mixed with stormwater into surrounding waterways, streets, sidewalks, businesses and even homes. Strategically, most wastewater treatment plants are located on coastlines to facilitate releasing treated wastewater back into the environment. For example, Chicago has wastewater discharge outfalls along the the Chicago River and Lake Michigan.

Now that I live in the Bay Area, I learned that San Francisco has several CSO outfalls that discharge into the Pacific Ocean and the Bay. Wastewater treatment facilities have outfalls near popular beaches for recreation where brave folks that swim and surf in the frigid water and chickens like me wade in ankle deep.

San Francisco City and County v. the Environmental Protection Agency

In the recent Supreme Court case, San Francisco was disputing permit language for its Oceanside wastewater treatment facility, which has an outfall pipe that discharges 4.5 miles into the Pacific Ocean near Ocean Beach. Under the Clean Water Act, all discharges of pollutants are unlawful and thus require permits – including (un)treated wastewater. EPA issues National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits that specify the amount of pollutants allowed to be discharged in a way that complies with federal and state water quality standards. Combined sewer overflows (CSOs), as a discharge of pollutants, are thus subject to NPDES permitting and must comply with the EPA’s CSO Control Policy and relevant water quality standards.

The NPDES permit for the Oceanside facility, expired in 2014 but had been “administratively reissued” ever since. Notably, San Francisco’s separate Bayside facility has also been operating under an expired NDPES permit, incurring Clean Water Act violations, and reason clean water advocates threatened to sue in 2024. In 2019, the EPA issued an NPDES permit renewal that included two end-result requirements or “generic prohibitions” at the heart of this case:

- “prohibits the facility from making any discharge that ‘contribute[s] to a violation of any applicable water quality standard’ for receiving waters;

- cannot perform any treatment or make any discharge that ‘create[s] pollution, contamination, or nuisance as defined by California Water Code section 13050.’”

San Francisco disputed the above additions. According to the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), which manages the city’s wastewater treatment plants, the new language: “inject significant uncertainty into all of our City’s permits and could force the City into at least $10 billion worth of capital expenditures [… ] The City is challenging the two unlawful, generic prohibitions.” Generic prohibitions here generally refer to the water quality of the receiving water—in this case, the Pacific Ocean. San Francisco is concerned that to be compliant with the “generic” permit language as approved by the EPA, they and their ratepayers would be saddled with unaffordable rates for years to come.

In 2023, the Ninth Circuit Court denied the City’s petition for permit review holding that the EPA is authorized to impose “any” limitations to ensure safe water quality standards are met. Elected leaders in San Francisco even lobbied against taking this to the Supreme Court. Ultimately, SCOTUS engaged “to decide whether the EPA can impose requirements like those at issue.”

If you couldn’t guess by now, SCOTUS ruled 5-4 for San Francisco effectively limiting the EPA’s authority to use certain permit provisions to prohibit water quality violations. While the ruling was relatively narrow, according to one expert, the dissenting justices (Barrett, Sotomayer, Kagan, and Jackson) found the Majority’s conclusion puzzling and “wrong as a matter of ordinary English” and go on to cite the several different dictionaries. In their dissent, they argue that the Generic Prohibitions referenced above are not categorically inconsistent with Clean Water Act.

With this SCOTUS ruling, things keep getting excrementally worse for public health

Upgrading combined sewer systems is costly which is partly why the City and County of San Francisco have been fighting this through the courts—to avoid making, what they argue, unnecessary upgrades. However their arguments found strange bedfellows with industry lobbies like the National Mining Association and American Petroleum Institute, who weighed in on San Francisco’s behalf in addition to expected support from groups like the National Association of Clean Water Agencies. In contrast, these entities all stand at odds with California and 12 other states who warn that the SCOTUS finding for San Francisco, would have “profound and drastic impacts on NPDES permits throughout the country.”

The recent SCOTUS ruling in favor of San Francisco compounds the 2023 Sackett decision eroding the Clean Water Act by stripping federal protections from critical wetland ecosystems as my colleague Dr. Woods has written about. It also shows the same lack of deference to federal and state scientists and agencies as last summer’s Chevron case, which another colleague, Dr. Merner, explains has critical ramifications for environmental regulations.

I am sympathetic to SFPUC and other utilities’ concerns about affordable rates and the ongoing need for massive federal infrastructure investments to ensure safe and clean water. At the end of the day, ratepayers foot the bill for massive infrastructure investments that are only barely subsidized by public funding. Household water affordability is critical especially because the water sector lacks “lifeline rates” that provide utility bill assistance for low-income households—which stands in contrast to the federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which is available for energy bills (and it’s still not enough). At the same time, the result of this legal battle and the SCOTUS ruling is the continued erosion of the EPA’s ability to enforce the Clean Water Act.

A. Fencl

Looming Deadlines analysis shows sh*t coming to your shores soon

All of the above is further complicated by climate change. UCS research found that wastewater treatment plants were among the critical coastal infrastructure at risk of chronic inundation at least twice a year by 2030 due to sea-level rise. When these plants are forced offline by rapid-onset inundation or by slower-moving hazards like sea-level rise, untreated sewage and other wastewater could pour into our rivers, bays, and coastal waters even in cities without CSO systems.

Californian ratepayers are also increasingly concerned about climate risks to our water resources. And fortunately, San Francisco and the SFPUC proactively consider and plan for climate adaptation. For example, the Oceanside Water Pollution Control Plant may be protected by a future $175 million sea wall approved last year by California’s Coastal Commission. If that Plant were to fail, “we could be spilling sewage onto the beach and hundreds of thousands of residents would not be able to flush their toilet” according to the SFPUC.

Now that I live in proximity to Ocean Beach, issues with the Oceanside facility permit and the potential for raw sewage to wash up along Ocean Beach during heavy rains are front of mind. Avoiding contamination and protecting public health needs massive infrastructure investment, like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and needs the EPA to be able to do its job—NOT rolling back key permitting provisions of the Clean Water Act. Yet, combined with this recent SCOTUS ruling, this administration’s EPA is determined to undermine public health and safety making America sick again, in every facet of our lives.