Nuclear war is commonly understood as a threat to the very survival of humanity. But even the task of maintaining a national nuclear weapons arsenal can have serious negative consequences for people, communities, and public health. As an environmental toxicologist and epidemiologist, I’m always looking for ways to further engage public health professionals and frontline communities with nuclear disarmament expertise in our work.

Through my work with the UCS Global Security Program, I’ve been able to connect with, and learn from, members of nuclear frontline communities still paying the human costs of the US nuclear weapons program, as well as experts like Dr. Tommy Rock at Northern Arizona University and Chris Shuey at the Southwest Research and Information Center. Dr. Rock and Mr. Shuey have been working for years with members of the Navajo Nation—where, for decades, people have lived with the health consequences of uranium mining for nuclear weapons production.

How nuclear colonialism has disproportionately harmed the Navajo people

Nuclear colonialism refers to the systematic exploitation of Indigenous lands and the Diné (what the Navajo people call themselves) by the US nuclear weapons program for the purposes of nuclear testing, uranium mining, waste disposal, and dosing humans with radiation without their consent.

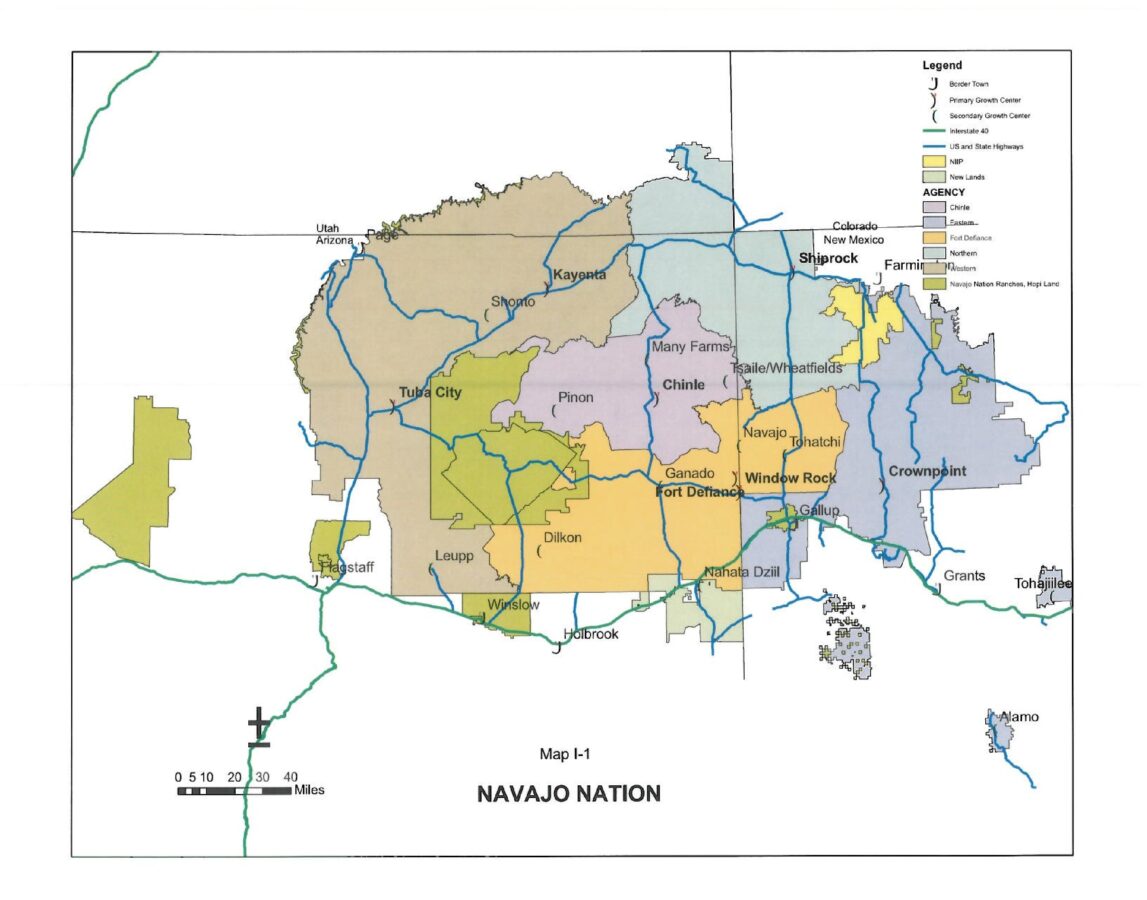

The Navajo Nation has historically been disproportionately burdened by the US nuclear weapons program, especially uranium mining. During more than four decades of domestic uranium production, nearly 30 million tons of uranium ore were mined on the Navajo Nation. Although the US government knew the risks of radiation to humans, many Navajo miners were still sent into mines with poor ventilation and safety regulations skirted.

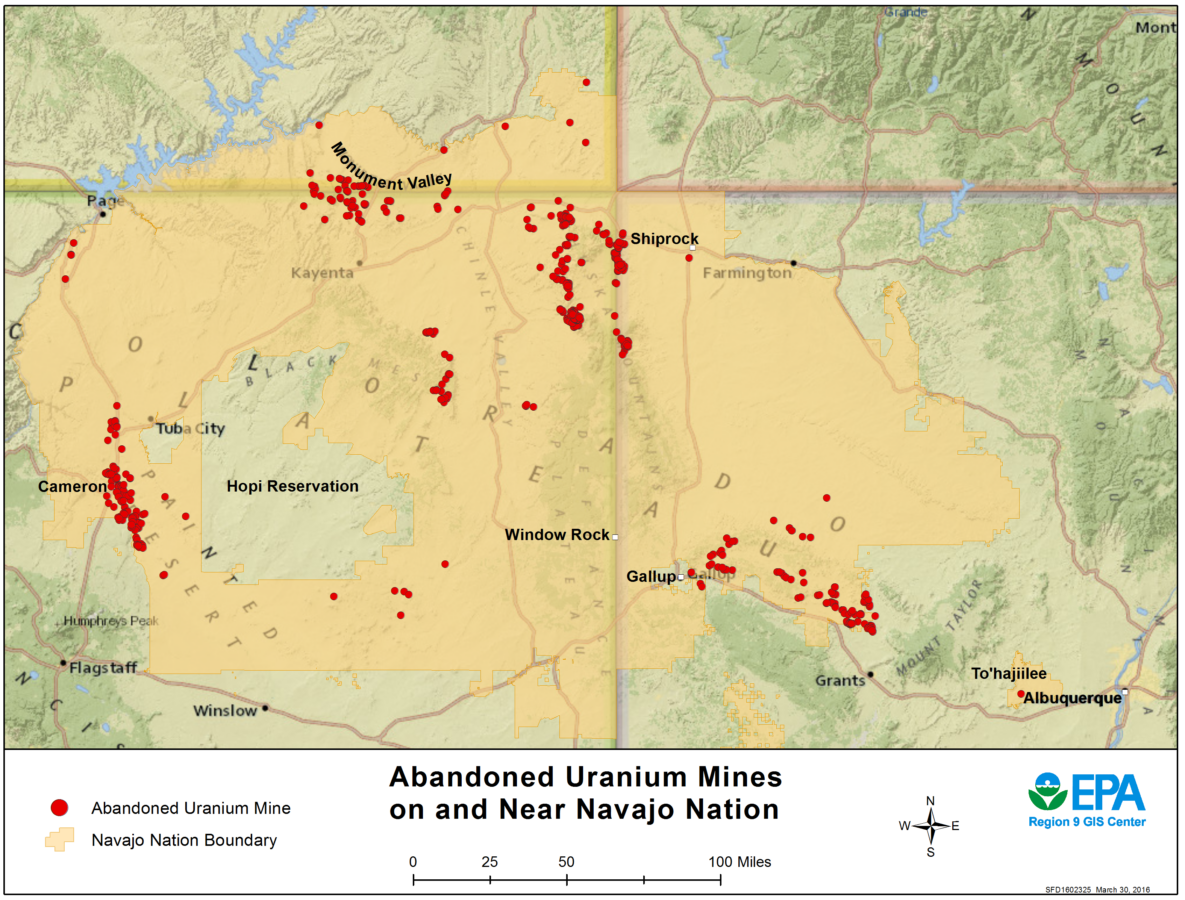

Dust from the mining and milling process was spread by workers into their communities, carried on their shoes and clothing into their homes. Moreover, the tons and tons of rock brought up from the earth were piled up in heaps before they were taken to the mill. These piles were exposed to the wind and rain, and contaminants from these piles leached into the groundwater and the nearby soil.

These disproportionate harms are not limited to the Navajo Nation; Indigenous land in general is disproportionately the target of nuclear waste. It is imperative to understand that nuclear material exposures, though they began decades ago in the region, are still having an impact today. Further mining—as outlined in a recent Executive Order—will only increase exposures in the environment and harm the same, already overburdened communities. Specifically, although the alpha particles released by uranium bounce off skin, they deliver high levels of energy to surrounding tissue. And with the fossil fuel-related pollution that comes with mining, climate change and air quality will be worsened as well for multiple communities in the region.

Cumulative impacts further burden an overburdened nation

Accidents compounded the harm and dangers of uranium mining to the Navajo Nation. The 1979 Church Rock, NM, uranium mill tailings spill released 1,000 tons of tailings and 93 million gallons of acidic wastewater into the Rio Puerco, traveling about 80 miles downstream to eastern Arizona. People who waded unknowingly into the river immediately after the spill suffered acid burns on their feet and legs, and an unknown number of livestock (cattle, sheep, horses) were also lost in the river. Before the Fukushima, Japan, accident in 2011, the Church Rock spill ranked second in the amount of radiation released behind only the Chernobyl meltdown in 1986 and above the Three Mile Island partial meltdown in 1979. Furthermore, about six times more radiation than was released in the spill was released into the Rio Puerco from 20 years of mine dewatering.

There is evidence of lung cancer and respiratory disease among uranium miners with no history of smoking. Among Navajo uranium miners compared to Navajo men with no mining history, those with a uranium mining history have 28.6 times more risk of new lung cancers between 1969 and 1993 (relative risk: 28.6, 95% confidence interval: 13.2-61.7%, n = 94). Additionally, research by the Navajo Nation Department of Health identified uranium mine workers who had elevated stomach, kidney, and biliary cancers, all of which are elevated in the Navajo Nation. This research often comes after decades of advocacy by the Diné, who were exposed to, and living with, the direct health consequences of decisions the US government made.

Nearly 40 years after the end of domestic uranium mining, there are still more than 500 federally recognized abandoned uranium mines left in the Navajo Nation alone, and more than 10,000 in the western United States. The legacy of the exploitation of the Navajo Nation has resulted in severe health disparities, environmental degradation, and the erosion of cultural heritage. Indigenous communities continue to fight for recognition, justice, and remediation in the face of ongoing nuclear colonialism in the modern era. Today, members of the Navajo Nation are still fighting for compensation for their communities’ exposure to radiation from nuclear testing and uranium mining.

All of these harms are in addition to natural gas and oil industry waste on the Navajo Nation, increased invasive bacterial cases, drought and heat waves associated with climate change that directly threaten Navajo ties to ancestral land, and a lack of local cancer care specialists. As of the end of 2024, life expectancy on the Navajo Nation is 58.8 years for males and 71.8 years for females—both of which are much lower than the US average of 78.6 years.

Research highlights the need for a more holistic approach

As a member of the Navajo Nation, Dr. Rock believes that addressing uranium contamination must reflect Navajo culture. He recommends using Navajo Fundamental Laws to guide policy development, making it more effective. Furthermore, Traditional Ecological Knowledge can assist the tribe in improving their quality of life, particularly around uranium contamination, which is a subject of particular interest in Rock’s research. His work takes an interdisciplinary approach to understanding and remediating the harms of uranium and arsenic in the Navajo Nation.

Dr. Rock and Mr. Shuey have collaborated on the Diné Network for Environmental Health (DiNEH), a community-based participatory research project focused on the health impacts of uranium exposure among the Navajo people. It has produced critical findings that exposures to environmental uranium and other metals have increased risks of kidney disease during the active mining era (1950-1986), and cardiovascular disease, autoimmunity, and a combination of metabolic diseases including diabetes during the period after the mines closed in 1986.

Moreover, Mr. Shuey and his collaborator Dr. Esther Erdrei, at the University of New Mexico, have worked on the Navajo Birth Cohort Study, which is now part of the National Institutes of Health ECHO+ (Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes) program. This long-term study examines the effects of uranium exposure on pregnancy outcomes and child development in the Navajo Nation. Preliminary findings indicate a troubling rise in developmental delays and pre-term births, and a correlation of women’s urine-uranium levels with uranium levels in their babies, suggesting uranium may cross the placenta.

The Navajo population assessed in the study has elevated exposures to many environmental metals at concentrations surpassing national all-races levels. This is so even though only about 14% of the cohort (n = ~1,800) live within five kilometers of an abandoned uranium mine, suggesting that environmental exposure is more widespread in the community than is currently understood and not confined to those living closest to mines.

Shuey and his colleagues at the University of New Mexico and the Southwest Research and Information Center are also involved in community-centered efforts to mitigate harm to communities from environmental exposures. The Thinking Zinc Clinical Trial explores whether zinc supplementation can mitigate the toxic effects of uranium exposure in Navajo communities. The study is part of broader efforts to find practical, community-based solutions for those affected by decades of environmental contamination.

It is long past time to redress some of the harms done

It is important to understand that much of the harms of nuclear weapons have been hidden from the public and today many people don’t know they are exposed.

And those who have learned they are exposed, like the Navajo Nation, are forced to carry the burden of proof—to prove their lives have been shortened by the decisions and actions the US government took without their knowledge or informed consent. At this time, it is more important than ever that the National Institutes of Health continue to fund research focused on environmental radiation exposures (especially long-term low-dose radiation) and associated health outcomes to better protect human health and community well-being. You can educate yourself about Indigenous health and find organizations to support financially that are operated by Indigenous experts and focused on improving Indigenous lives.

Additionally, despite the risks and harms related to nuclear materials exposure in the environment, not a single radiation health or emergency center has been built in or near the Navajo Nation by the US government to alleviate these harms. Certainly, the United States should at least provide access to quality health care and specialists for a sovereign nation with which it has entered into longstanding treaties.

A concerted and well-funded effort is needed to mediate the harms caused by the nuclear weapons life cycle. By better protecting the most vulnerable populations, such as those who live off the land and spend more time in the environment—like many Diné—federal regulatory scientists can better serve everyone. As the second Trump administration turns to increasing the mining of essential minerals in the United States, the Diné are still waiting for compensation, local access to medical care specialists, and more action by US officials to ensure their way of life can be maintained for generations to come.

NOTE: The original version of this article erroneously stated that autopsies had been performed without permission on Indigenous people. The person in the case cited was not Indigenous.