Just half of road funding is paid for by road users through funding mechanisms like fuel taxes or vehicle registration fees, and the largest share of that (the federal gas tax) has not been raised in over 30 years. However, some in Congress have tried to blame the rise of electric vehicles and fuel-efficient gasoline-powered vehicles for the federal government’s struggles to fund decades of road-building.

Below I walk through why the federal government’s ability to pay for highways has nothing to do with electric vehicles and everything to do with Congress’s insatiable desire for road-building.

A lot has changed since Congress last adjusted transportation funding

The Highway Trust Fund is responsible for nearly all of the federal government’s spending on transportation, with revenue sourced predominantly from fuel and excise taxes and, increasingly, injections of capital from the General Treasury. Apart from these intermittent transfers, Congress has not meaningfully changed the source of revenue for the Highway Trust Fund since the last increase in fuel taxes, which went into effect on October 1, 1993.

How long ago was that? Well, just ¼ of US adults had access to a computer, and just 2 percent of the country used the Internet in 1993. And forget “smart phones”—the first cell phone capable of text messaging debuted in 1993, along with the first battery-operated cell phone.

Fittingly, The X-Files debuted just two weeks before the last change in federal fuel taxes went into effect—this iconic TV show dealt with government bureaucracy and the unexplainable, topics which both sadly resonate in trying to understand the government’s approach to the transportation system.

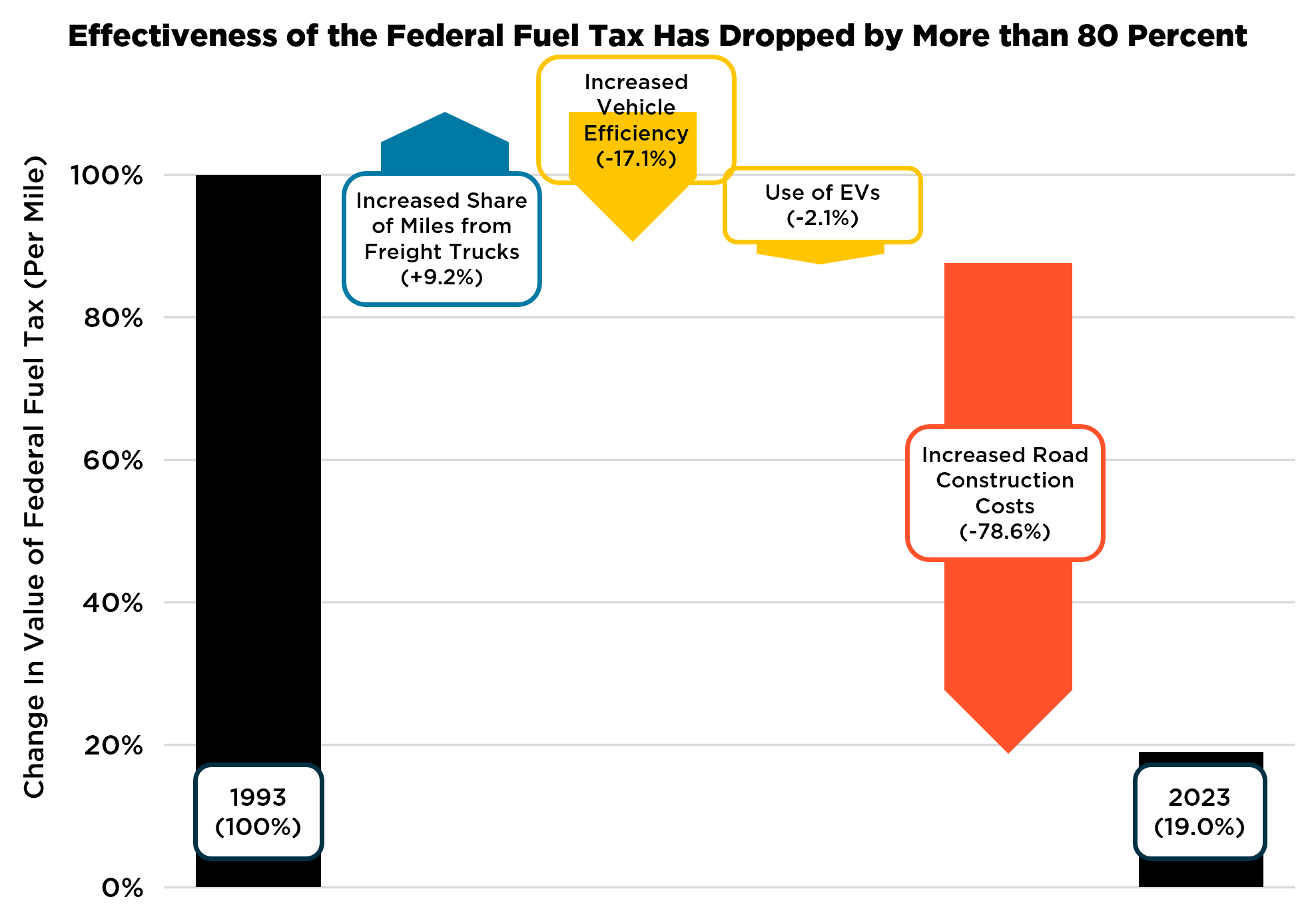

As one can imagine, the passage of time has had a large impact on the value of the federal fuel tax. The current tax rate on a gallon of gasoline is just 18.4 cents—and that 18.4 cents doesn’t mean the same today that it did when the tax went into effect in 1993. Inflation, the general measure of the cost of consumer goods, has more than doubled since then, which means that the value of the tax to the households paying it is less than half what it once was. It also hasn’t kept pace with the cost of gasoline, which has increased by nearly a factor of three—thus, the federal government’s share of the cost of a gallon of gas is about 1/3 what it used to be. And when it comes to what you can buy for that share, costs of road construction have far outpaced general inflation—that revenue buys today less than 1/4 of what it used to back in 1993.

Factoring in both the amount of tax generated and what that tax is financing, the effectiveness of the federal fuel tax has dropped by more than 80 percent since it was last changed in 1993. And the main reason for that is our ever-more-expensive highway system.

Roads are expensive, and highway expansion even more so

Construction costs have skyrocketed for a number of reasons, but two stick out: a reduction in competition resulting from consolidation in the construction industry and a reduction in capacity at the state departments of transportation to facilitate competitive bidding. But it isn’t just that construction costs have exploded—it’s that the highway system itself is a positive feedback loop of costs begetting even more costs.

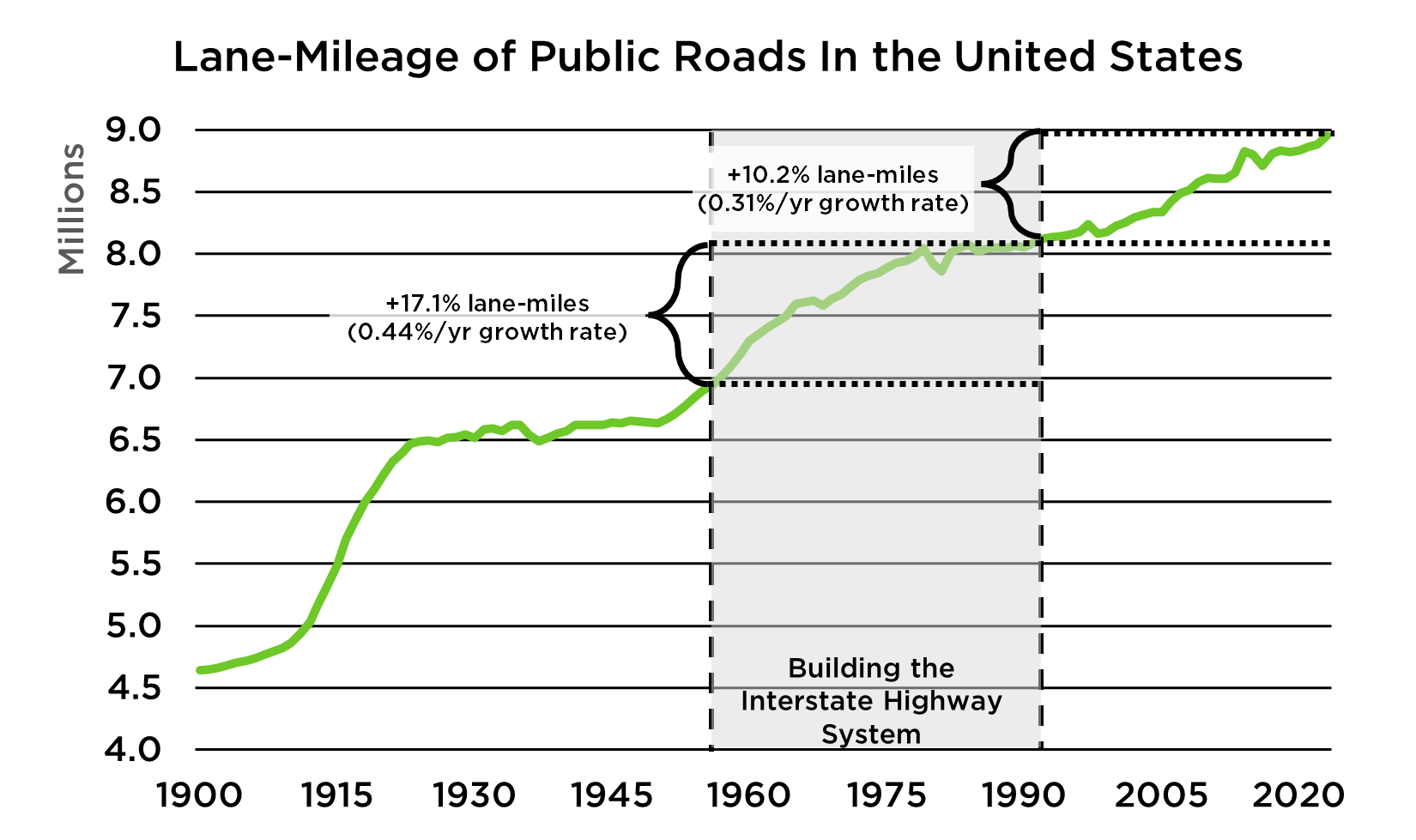

The original interstate system conceived under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 was completed in 1992, but rather than stop then and there, highway expansion has marched onward. Public roads nationwide have increased in lane-mileage by over 10 percent since the “completion” of the Interstate Highway System. This rate of expansion represents 70 percent of what it was during the construction of the Interstate Highway System—despite a theoretical completion of the system, we’ve barely curtailed expansion.

Highway expansion is not a one-time construction cost—new roads have to be repaired indefinitely, simply adding to repair costs for infrastructure already built. Moreover, expanding highways results in an increase in usage not just of the new lanes of road but also for the built system, too, through a phenomenon known as induced demand, whereby you reduce barriers to driving and, in turn, increase the amount of driving that occurs. Commercial trucks, for example, will increase traffic on an interstate by between 19 and 29 percent for every 10 percent increase in capacity, resulting in a net negative impact on traffic flow.

As the country has continued to build out the freeway system, the infrastructure built creates an ever-increasing cost spiral—even after adjusting for the increased cost of construction, the amount spent on repair has more than doubled since 1993, thanks in large part to a doubling of miles traveled by the largest and heaviest vehicles on the road (commercial trucks) and an overall increase in travel by over 40 percent. Perhaps this is why the country has a backlog of over $1 trillion in maintenance.

It is the unsustainable costs of our highway system that is bankrupting the Highway Trust Fund, and this leads to an ever-increasing share of general public funding to bail it out if nothing changes. Highways are a costly use of land, with one study finding that the costs of highway expansion outweigh the benefits by 3 to 1, even without factoring in external social harms like health impacts from added traffic pollution. It’s clear we should be rethinking the status quo of never-ending road expansion.

Cars are more efficient now…and that’s a good thing!

Because the politics of dealing with the actual problem of funding our highway system is hard, there’s a desire to find a scapegoat. In this case, politicians have turned their attention to how much more efficient our vehicles are.

Both passenger cars and trucks and heavy-duty vehicles have gotten more efficient over time. That means that drivers can go farther on a gallon of gas or diesel. This is an unabashed good thing—improving efficiency is a critical part of reducing global warming emissions, and it saves drivers money, something that is especially important with prices for households on the rise. And when a growing share of those efficiency gains are about eliminating oil use and the volatility of gas prices entirely from the equation for families thanks to electrification, improvements in efficiency are a very good thing.

However, since the funding for the Highway Trust Fund is largely based on revenues from fuel use, using less fuel per mile means that part of the reduced costs of fuel to consumers come with reduced contributions to the Highway Trust Fund. But is this actually a big deal? Compared with other factors, this is a drop in the bucket.

Since 1993, the passenger cars and trucks on the road have improved their fuel efficiency by almost 19 percent. Commercial vehicles have improved by 18 percent. The disproportionate increase in travel by diesel-powered trucks means that the loss in revenue per mile traveled is only just over 11 percent as a result of efficiency improvements. Compared with an erosion of buying power for the HTF of over 78 percent as the result of skyrocketing construction costs since 1993, or even just the erosion of value of 54 percent related to general inflation, it’s clear that the story of HTF insolvency is not related to efficiency.

Electric vehicles are a small share of potential revenue

Even though EV drivers, like all of us, already pay for roads through general tax revenue, some still claim that it’s unfair that EV drivers don’t pay a fuel tax. But this both ignores the way roads are funded and the taxes that EV drivers already pay for electricity usage.

The notion that EV drivers are getting a free ride is just plain wrong, thanks in part to taxes and fees levied at the state and local level, where more than 80 percent of road funding comes from. In 36 states, there is even already a net tax penalty for driving an EV compared to a gasoline vehicle thanks to the combination of taxes and fees already in place. But even at the federal level, the lack of a federal fee on EV drivers is a negligible contribution to any shortfall in the Highway Trust Fund.

Today, we estimate that EVs are responsible for just over 2 percent of miles traveled in the U.S. Last year alone, highway construction costs increased by 6 percent. Even as EVs become a growing share of the vehicle fleet, we estimate that they will make up just 3 to 8 percent of road travel between now and 2030, depending on the degree of to which the current administration succeeds in eliminating EV incentives and protective vehicle regulations.

At just 3 to 8 percent of mileage traveled, charging EV drivers a mileage fee comparable to that of gasoline-powered vehicles would have little impact on the solvency of the Highway Trust Fund, which spends about 60 percent more than it takes in. However, it could act to dissuade EV buyers, particularly if accompanied by the elimination of policies designed to grow a still nascent market. Given the health and climate benefits of switching to electric vehicles, we should be focused on enabling that transition, not thwarting it with unnecessary fees.

Congressional EV fees are both counterproductive and unfair

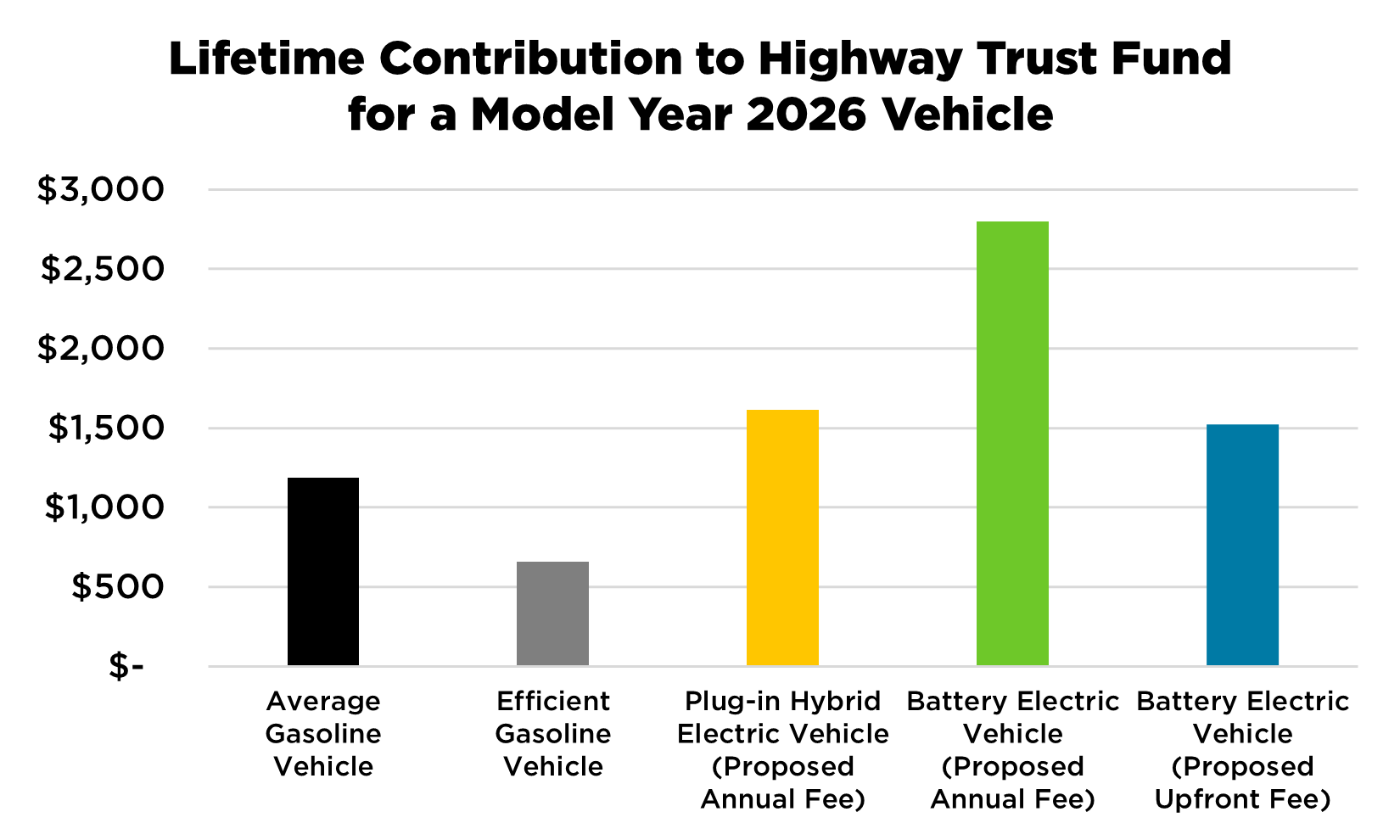

It’s bad enough that the highway lobby is pitching Congress that EV fees are a meaningful way of addressing transportation revenue (as noted above, they’re too small to make a dent). It’s worse still when that approach not only runs directly counter to our need to move away from a petroleum-focused transportation but is punitively designed to overburden those who are making the choice to get off gasoline.

One proposal from Congress from U.S. Representative Dusty Johnson (R-SD) and Sen. Deb Fischer (R-NE) is designed to disincentivize EV ownership by forcing an upfront surcharge on EVs. New gasoline car buyers pay fuel taxes when they fuel, gradually over the lifetime of the vehicle. If a vehicle is sold, the next owner will pay for the continued fuel consumed, along with any associated fuel taxes. The Johnson and Fischer bills, however, impose two fees upfront on EVs, targeting prospective EV owners—the first is a flat $1000 fee, no matter any characteristics of the battery-electric vehicle regarding weight or efficiency. The second is an additional fee of $550 on the manufacturer (which will be passed on to the vehicle purchaser) for every battery module weighing more than 1000 pounds—while according to the bill authors this provision is targeted at heavy-duty electric trucks, the ambiguity in language could ensnare the over 90 percent of light-duty EV packs that meet that weight threshold as well.

An upfront surcharge on an electric vehicle, particularly one that doesn’t exist on a gasoline vehicle, would disproportionately burden EV drivers with the costs of roads compared to other drivers. Under current policy, about 8 percent of vehicle miles from now through 2030 would be driven on electricity—with the proposed fees, and assuming Congress does not let the current fuel taxes expire in 2028 as they are set to do, EV drivers would pay about 20 percent of all federal taxes collected from passenger cars and trucks in that same timeframe, hardly a “fair share.”

Another recently reported proposal would put an annual fee of $200 for battery-electric vehicles and $100 for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, but it’s again designed to force EV drivers to pay a significantly higher share than gasoline drivers. If Congress is going to enact a fee on EVs, it should be compatible with how we assess fees on the rest of the fleet. The current fuel tax acts as a market signal to drivers and rewards efficiency—punishing drivers for using vehicles that are three times as energy efficient as average while rewarding drivers using vehicles less than twice as efficient as average is an inequitable mess.

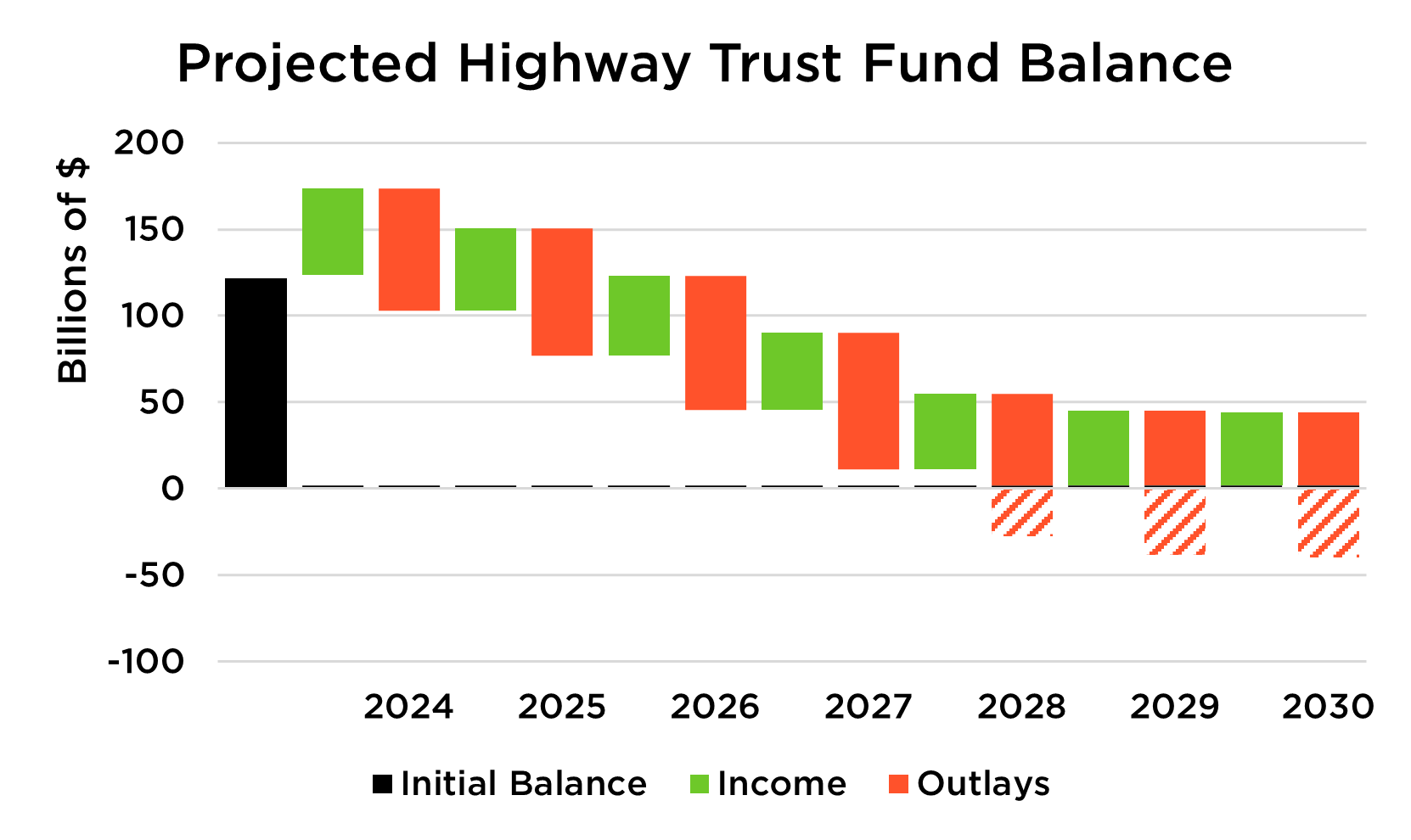

The highway trust fund is broken—EV fees aren’t going to fix that

The Congressional Budget Office showed in their latest analysis of the Highway Trust Fund that the Highway Trust Fund is expected to spend $213 billion more than it takes in ($261 billion) for fiscal years 2025 through 2030. We estimate even the unfair proposal put forth by Congress would raise between just $7-33 billion over that same time frame, putting hardly a dent in the deficit even as it penalizes families for reducing global warming emissions and public health harms from their vehicles.

The biggest problem with the Highway Trust Fund isn’t what families are contributing—it’s the poor outcomes from that investment. Adjusted for inflation, the federal government may be spending half what it used to on brand-new highways, but that still means hundreds of miles of new highways every year, at a cost of over $10 million per mile. On top of that, major construction projects on existing highways frequently result in increased lane-miles—just last year we increased lane-miles on over 10,000 miles worth of roads, at a cost of just about $700,000 per mile.

The result of this expansion is a highway system that is not just expensive but unsustainable. The federal government has more than doubled its spending on road repair since 1993, even after adjusting for inflation, and yet the federal share of spending on repair has actually gone down because the National Highway System is a giant money pit, emptying federal, state, and local coffers alike, with total maintenance costs 3.5 times higher in 2023 than in 1993, even after adjusting for inflation.

Funding more roads won’t get us where we need to go

Until our infrastructure reflects a system that works for everyone, we should not be asking families to invest more of their hard-earned money in it. While prioritizing repair over expansion through “fix it first” or even reducing road lanes via “road diets” may be smarter ways of investing in our roads, that’s hardly typical of where our federal dollars go.

If Congress is going to evaluate the effectiveness of federal transportation funding, it must look at both sides of the ledger, not just where the money is coming from but where it is going. Otherwise, the costs will continue to balloon unsustainably, as we see with the Highway Trust Fund.