About half of our goods (as measured in ton-miles of freight) travels by truck before reaching its destination, whether that’s in last-mile shipping from a warehouse, offloading freight from a railyard, direct ground shipping, etc. This makes the trucking industry a critical piece of our freight infrastructure and, because of the role goods play in our daily lives, a vital piece of the economy.

However, the value of the trucking industry in our daily lives does not give the industry a free pass from all of its negative impacts, whether that is the pollution exacting its toll on frontline communities, the heat-trapping emissions from this fossil-fuel-centric sector, or the disproportionate damage done to roads and bridges.

Unsurprisingly, representatives of the industry were on Capitol Hill earlier this year to ask for the federal government to weaken safety and emissions regulations, but incredibly they also asked for Congress to bolster highway funding while simultaneously requesting the elimination of the federal excise tax on new heavy-duty trucks that represents nearly 40 percent of the industry’s contribution to the Highway Trust Fund.

The trucking industry claims it wants to “pay its fair share,” but as I show below, today the industry falls well short of such funding, and if Congress were to listen to them, this gap would be even wider in the future. A close look at roadway costs attributable to trucks suggests a fair contribution from the trucking industry to roads and bridges would be about $150 billion annually, just over half of all highway expenditures, a substantial increase from the $60 billion they currently contribute to surface transportation each year.

What impact do trucks have on our infrastructure?

The trucking industry pretends that because they pay more taxes per mile traveled than passenger vehicles that this means they are already overburdened when it comes to funding our highways, but that ignores the obvious: heavy trucks weighing generally up to 80,000 pounds (and, in some states, as much as twice that!) clearly do more damage to our roads per mile traveled than your average passenger car or truck weighing around 4,000 pounds.

If we want to define “fair share” as the trucking industry claims, we need to think about the relationship between the damage caused by different types of vehicles and their relative contributions to funding.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) conducted a detailed study looking at the relationship between road damage and weight and found that the damage to roads are proportional to axle weight raised to the 4th power. For simple comparison, this means that a 5-axle tractor-trailer at its maximum federal weight of 80,000 pounds does roughly 10,000 times more damage per mile traveled than a 4,000-pound passenger vehicle (5 axle passes x (80,000/5)4 for a truck vs 2 axle passes x (4,000/2)4 for a car)

This study was largely affirmed in the 1980s, and this 4th-power law continues to undergird general practices around road design today in the United States. At the same time, there are nuances in the relationship related to things like the condition of the road (e.g., is it already damaged?), tire type and pressure, materials and design of the pavement, etc.

One study, funded by the trucking industry, found a much lower exponent (~2.31, as compared to 4) for flexible pavements (asphalt), which are today generally preferred to the rigid pavements (concrete) originally studied in the AASHO analysis 65 years ago. In that case, a comparison between an 80,000-pound truck and 4,000-pound car would yield a difference of around 300 times more damage per mile. Since this analysis was paid for by an industry seeking to limit its responsibility, this likely represents a lower-bound on the impacts of heavy-duty vehicles on roads relative to passenger cars and trucks.

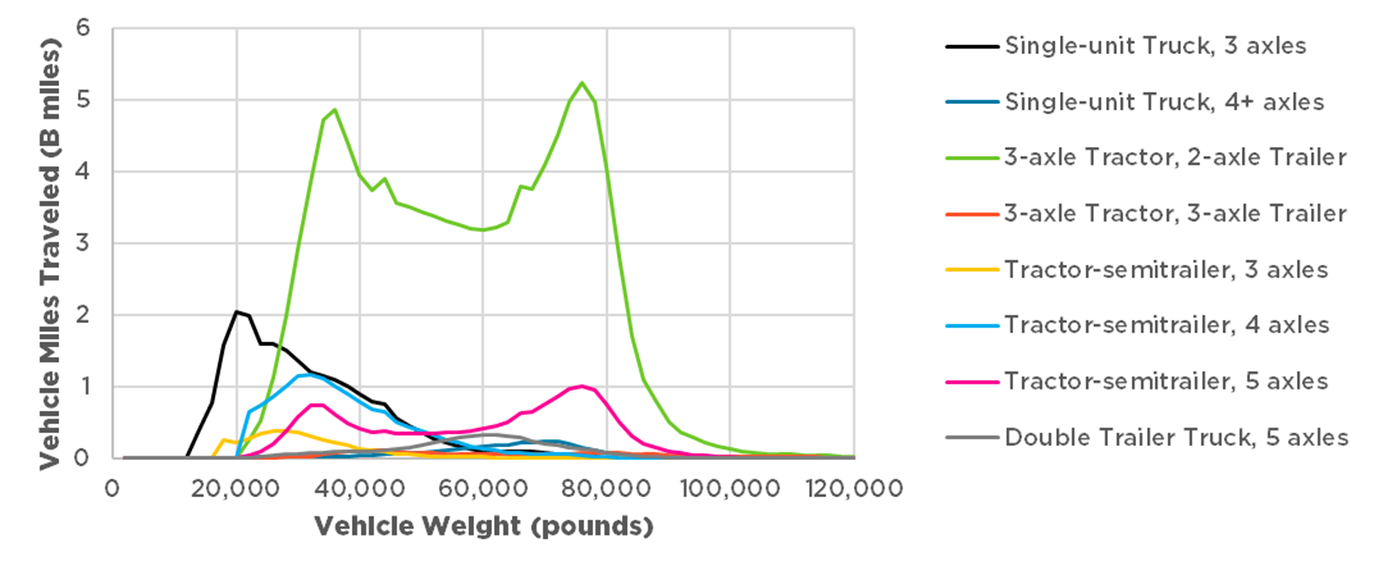

Given the power laws above, we can estimate the relative damage of personal versus commercial vehicles in the United States. The Federal Highway Administration regularly collects detailed data on truck travel in the United States, allowing not just looking at mileage by weight but also by the number of axles on the truck. In this data we see clearly peaks at weights associated with an empty truck (and its trailer), another larger peak in mileage at the maximum federal weight a truck can maintain (for the share of trucking mileage that “weighs out”), and a broad distribution of mileage between (for the larger share of trucking mileage that “cubes out”, or fills its trailer before packing goods to the maximum weight). Supplementing this with data from the Vehicle Inventory and Use Survey for single-unit trucks not captured in this data set as well as curb weight data from EPA for passenger vehicles, we can compare the relative damages. (Further detail is provided in our methodology.)

Despite accounting for just 11 percent of the more than 3 trillion miles of travel on US roads annually, we estimate heavy-duty trucks are responsible for at least 91 percent of the wear and tear on those roads (and as much as 99 percent if the fourth power law holds!). Most of this damage comes from over-the-road freight: tractor-trailers are responsible for nearly 80 percent of the annual deterioration of highway infrastructure despite representing just 6 percent of all miles traveled.

A not-so-fair share

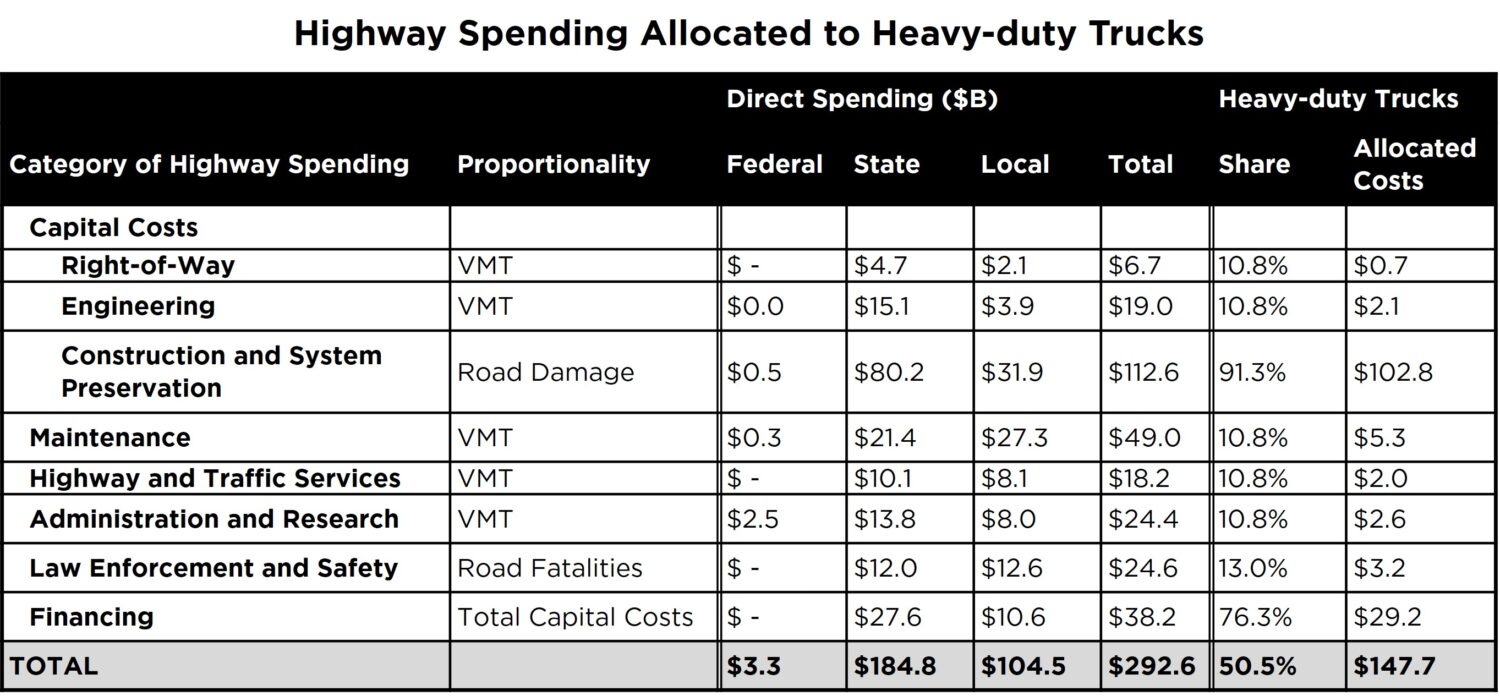

While construction costs are directly related to wear and tear from traffic, some additional highway expenditures are more closely related to traffic flow. For example, it could be argued that research and administrative costs or maintenance of the shoulder could be allocated based on the relative share of vehicle miles traveled. In the case of safety and law enforcement, it would be appropriate to consider the crash risks of the relative vehicles and their safety impacts. But by far the biggest share of highway costs is for construction, which should be proportional to the upkeep of that infrastructure—even when built as new, a project’s costs and amortization all reflect the load-bearing capacity of the traffic it’s being designed to carry.

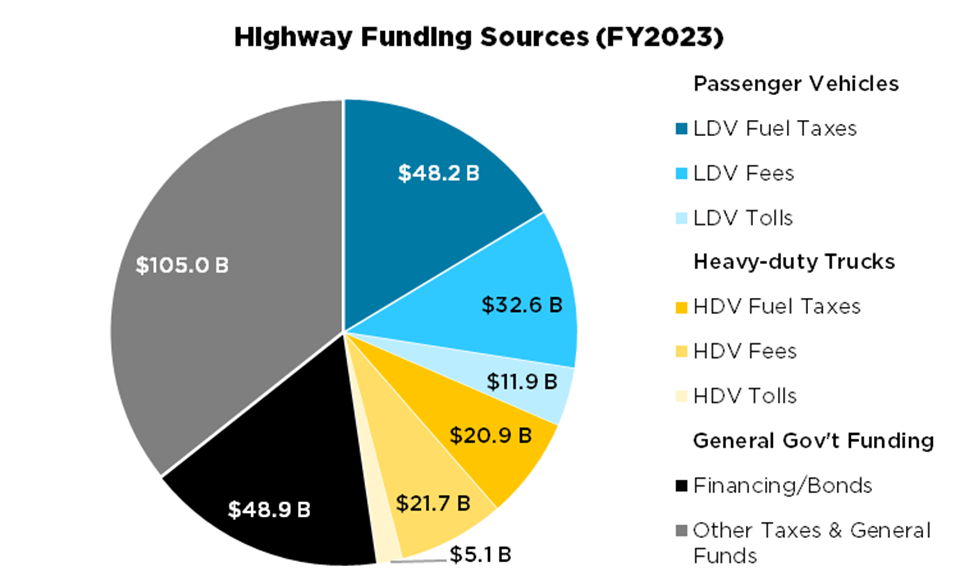

Because trucks are heavier and less fuel-efficient (per mile) than passenger vehicles, trucks do pay more per-mile than passenger vehicles in local, state, and federal taxes and tolls for highways (roughly 16 cents per mile traveled for heavy-duty trucks compared to 4 cents per mile for passenger vehicles). However, you know who pays even more for highways? Everyone else. The general public, which includes non-drivers, pay the most towards our highway system because our highway spending is so out of control we have to pay for it through general government funds over and over again.

If we allocate highway costs to the vehicles traveling on the roads, including non-construction costs, we see that heavy-duty trucks should pay for just over half of all highway expenditures. Today, they currently contribute approximately just $60.1 billion in federal, state, and local taxes and fees, with a share of that contributing to non-highway expenditures (transit, government operation, collection fees, etc.), varying by jurisdiction. But, if we ignore transfer payments and just consider the gross inputs and outputs, taxpayers at all levels of government are subsidizing the trucking industry by $87.6 billion every year just in highway costs. By contrast, the direct subsidy for highway spending for personal vehicles is just $22.6 billion annually.

Rebalancing the books

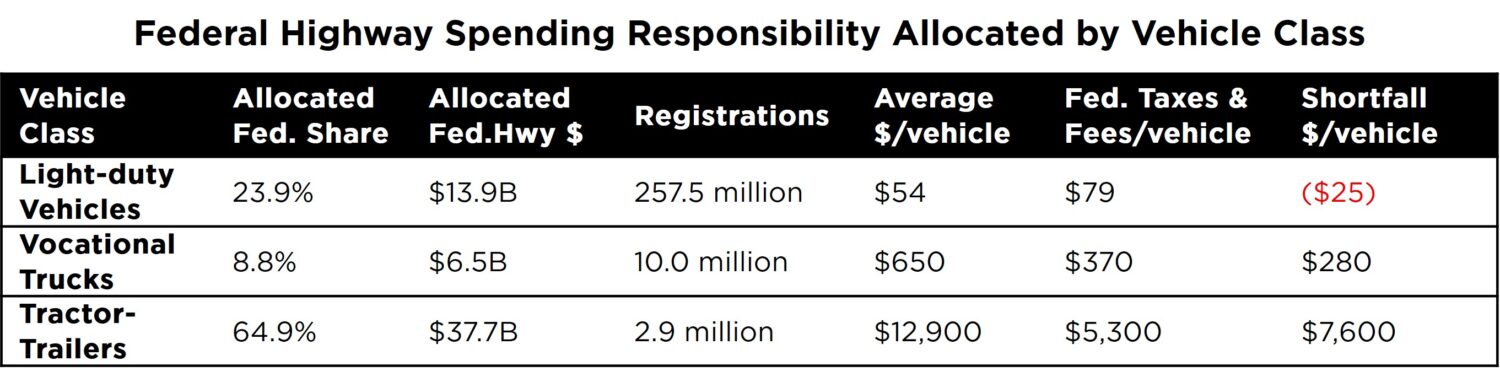

The costs above are focused on total spending at all government levels, but focusing solely on federal spending, which includes transfers to states from the Highway Trust Fund, makes an even stronger case because federal dollars go almost entirely towards capital spending. We estimate that the trucking industry is responsible for $44.2 billion of federal highway spending, or nearly three-quarters of federal highway expenditures. Currently, trucking only contributes $19.2 billion annually to the Highway Trust Fund highway account, which means that the trucking industry receives a federal highway subsidy of about $25.0 billion every year.

And yet, despite this subsidy, the trucking industry is advocating to cut their own share of taxes by eliminating the federal excise tax (FET), which is a 12 percent tax on the purchase of new heavy-duty trucks. This tax represents 37 percent of the industry’s federal contribution to paying for the transportation system.

Just to stay even with today’s contributions, the proposed elimination of the FET would require an 18.0-cent increase in the federal diesel tax, shifting the tax from 24.4 cents to 42.4 cents per gallon. But that does nothing to pay back the American taxpayer—paying for the trucking industry’s highway subsidy through an increase in the diesel tax would require more than tripling the federal tax on diesel, with an increase of 62.9 cents per gallon, irrespective of what happens to the FET. But because fuel economy and global warming emissions standards still on the books are ensuring trucks get more efficient, and because a fuel tax is only indirectly connected to usage via efficiency, which can change over time, even this increase may not solve the long-term imbalance.

A better solution would be something that directly considers the long-term impacts of trucks, such as a weight-based mileage fee, also known as a weight-distance tax. Unlike a private vehicle mileage fee, there are no privacy concerns for these commercial vehicles, and implementation would be relatively straightforward because of recordkeeping already in place: much of the trucking industry has to maintain electronic logs for the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration that include location data, and interstate trucks already participate in programs like the International Registration Plan (IRP) and the International Fuel Tax Association (IFTA) which track mileage in different jurisdictions. And some type of these fees are already implemented in states, including New Mexico, New York, and Oregon.

The public also pays for trucking’s health and environmental costs

It’s worth noting of course that an increased user fee on trucking will fall far short of paying the full costs of trucking. While the public subsidizes the trucking industry’s impacts on freeways by $87.6 billion a year, we also force communities near roadways to pay for between $71 billion and $98 billion per year in health costs resulting from the unmitigated pollution from those trucks, according to EPA models. And based on the latest estimates of the social costs of global warming emissions, the U.S. trucking industry is causing $99 billion in global warming-related public harm annually as the result of its petroleum dominated inputs.

As we look to improve the transportation system overall, we need to use all policy tools at our disposal to drive these impacts downward and ensure the trucking industry is paying for its harms in the meantime.

The trucking industry can afford to pay its fair share

There is no reason for the American taxpayer to foot the bill for a trillion-dollar per year industry. And we don’t need to.

For the heaviest trucks, the tractor-trailers that travel the largest miles per year and are responsible for the lions’ share of road damage, fuel costs have averaged just 23 percent of the hourly costs of doing business over the past decade. Increasing the federal diesel tax by 62.9 cents per gallon to balance the costs of highway upkeep would be less than the price of diesel has dropped over the past two years and would represent just a 17 percent increase. That is an impact on freight profit margins of just 3.5 percent, which is similar to the year-to-year variation due to the cyclic nature of the freight industry.

A weight-based mileage fee and/or increased diesel taxes to better account for the costs of trucking may not be the only permanent solution for federal transportation funding—we should be thinking about transportation as a public good, and that requires public investment in mobility writ large, not just more roads. But if the trucking industry wants to push for “fair pay” as part of its push for bolstering spending on roads, it needs to quit scapegoating electric vehicles and start looking in the mirror because trucks would be paying a whole lot more for road use than they do today.

The methodology and dataset for this analysis can be found at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/M6FOFP.