Transportation is the largest source of US global warming emissions, accounting for 28% of total emissions in 2022. Electrification remains the fastest way to cut emissions from vehicles and is critical to reduce climate damage in the coming decades. Even when considering electricity emissions, the average battery electric vehicle (BEV) is responsible for one quarter of the average emissions for new gasoline vehicles in 2024, equal to the emissions of a 100 mpg gasoline car.

Sales of EVs have been strong, with over 1.2 million annual EV sales in the US since 2023. However, fully electric vehicles are facing significant headwinds in 2026, as the federal administration and Congress have gutted vital vehicle regulations and cut funding that was accelerating the transition of passenger vehicles from gasoline to electricity. Even with these changes in federal policy, the global situation is largely unchanged, with increasing production of EVs to meet the demand of drivers and emissions regulations. Globally, EV sales hit new highs with EVs making up over 20% of new car sales in the second half of 2025.

Some automakers have responded to these changes in the US by signaling a pullback on EVs broadly and for some a switch from fully electric vehicles to plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), vehicles that can be refueled by both charging on electricity from the grid and by using gasoline (or diesel). PHEVs sound like an attractive option: electric drive without the concerns of where to charge as they can also use existing gasoline refueling infrastructure. But there could be significant downsides, for drivers, automakers, and the environment.

A quick primer: Hybrids, PHEVs, and EREVs

First, there are hybrids that are basically just more efficient gasoline-only vehicles. These “conventional” hybrids like the original version of the Toyota Prius do have electric motors that can drive the wheels, but the energy to recharge the battery comes either from regenerative braking or from the gasoline engine. There’s no way to plug in these hybrids and therefore 100% of the energy to move the vehicle ultimately comes from gasoline. The electric motors, batteries, and regenerative braking systems do increase the efficiency of these vehicles, but ultimately they are still gasoline-only vehicles.

Second, there are plug-in hybrids or PHEVs. All PHEVs for sale in the US at the start of 2026 are parallel or power‑split hybrids. What this means is that the gasoline engine can mechanically drive the wheels alongside an electric motor. Most current PHEVs can operate solely on electric motors if the battery is charged, but some do require the gasoline engine to help when high power is needed, like during a rapid acceleration to merge onto a freeway. These PHEVs can replace some gasoline use with grid electricity, but their effectiveness depends on how often they are plugged in and the design choices made, such as the electric motor power and battery capacity. They can show high efficiency (especially in regulatory testing), but real‑world emissions hinge on drivers’ charging behavior and the number of long trips that exceed the battery range. PHEVs with this design often have relatively short electric ranges before switching to gasoline-powered operation. For example, the 2025 Toyota RAV4 PHEV has an estimated electric range of 42 miles.

Finally, there are extended‑range electric vehicles (EREVs). EREVs are a type of PHEV that are electric‑first by design: the electric motor drives the wheels 100% of the time and the gasoline engine runs only as a generator when the battery charge is low. This type of PHEV where there is no mechanical linkage between the gasoline engine and the wheels is also known as a serial hybrid. In general, EREVs have a larger battery capacity (and therefore higher electric range) than PHEVs with a parallel hybrid design. While there have been few examples of EREVs sold to date (for example the BMW i3 REx), more automakers are planning on releasing EREVs in the coming years. Ford announced that it will produce an EREV version of its F-150 pickup truck to replace the now discontinued all electric F-150 Lightning. Newer electric vehicle brands are also promising EREVs. For example, Scout Motors (a new VW Group brand) is planning on offering an EREV version of their upcoming electric SUV.

What the data say about real‑world PHEV emissions

While PHEVs have been helpful in the transition to fully electric vehicles, multiple studies have found that current (parallel) PHEVs drive far more on gasoline than is assumed in certification testing, leading to higher fuel use and global warming emissions than predicted. For example, the International Council on Clean Transportation found that PHEVs in the US may have real-world fuel consumption 42%–67% higher than the EPA fuel economy labeling states. This gap is likely driven by infrequent charging and powertrains that engage the engine for additional power while the battery is still charged. While some PHEV drivers do attempt to maximize miles driven on electricity, others may not charge their vehicle at all, driving their PHEV as a conventional, non-plug-in hybrid. A recent study of US Toyota RAV4 PHEV drivers showed that less than 80% recharge their PHEV consistently and 9% are essentially not charging their vehicles at all (less than 1 charge per 10 driving days).

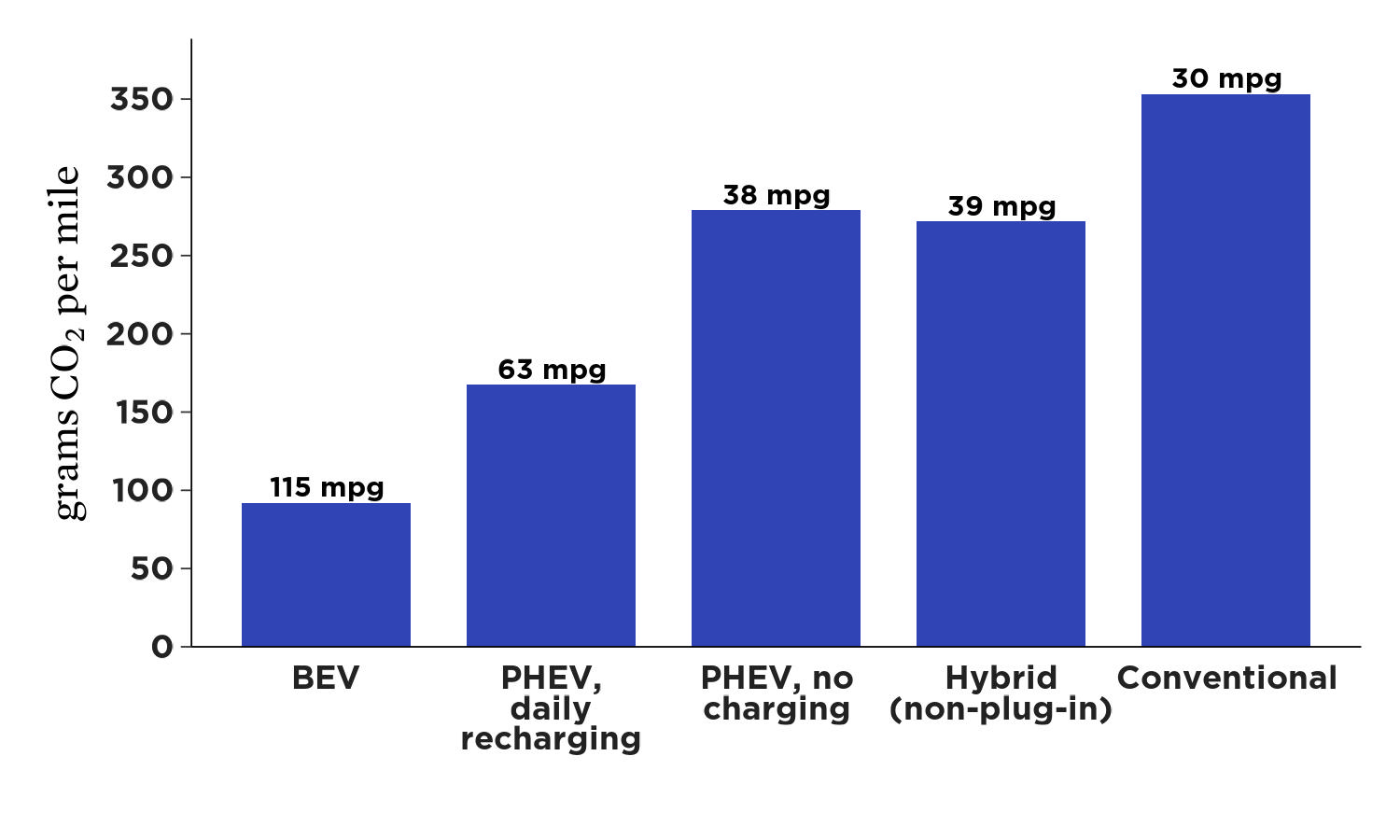

Even when parallel drive PHEVs are plugged in, their emissions are significantly higher than fully electric BEVs, both due to the use of gasoline and the lower efficiency of most PHEVs compared to BEVs. Using US average data, a Toyota RAV4 PHEV when recharged daily would have almost double the global warming emissions per mile than a Toyota bZ BEV. And if the PHEV is not plugged in, the emissions from the PHEV will be triple the BEV emissions.

Current PHEVs don’t prepare drivers or automakers for an electric future

All PHEVs currently for sale are parallel PHEVs. Most have an electric drive range between 20 and 45 miles and lack the ability to use fast-charging stations. This short electric range means that a large fraction of driving will be powered by gasoline. The short electric range and lack of fast-charging capability also means that drivers on longer trips will search for gasoline stations and not charging stations so today’s PHEVs don’t actually help drivers transition to fully-electric vehicles.

Parallel PHEVs can also be a dead end for vehicle manufacturers. The technology used to integrate gasoline engine power with electric motors isn’t needed for fully electric vehicles and so research and development spending on parallel PHEVs will likely not help automakers design the next generation of battery electric vehicles.

EREVs as more promising bridge to fully electric vehicles

EREVs are series hybrids with larger batteries than a parallel PHEV. The wheels are always driven by the electric motor, and the gasoline engine is just a generator. This design will produce a similar driving experience to a fully electric vehicle, and it’s expected that EREVs will have battery capacity and fast charging capabilities much more similar to a battery-electric vehicle than current PHEVs. This means that drivers will become more familiar with charging both at home and on trips. It also means that manufacturers will be designing EREVs that share many components with a battery electric vehicle, making the transition to fully electric vehicles simpler and more cost effective. For some models, it is likely that automakers will be able to offer both EREV and BEVs with minimal design changes. This similarity between EREVs and BEVs is also important given the potential for improvements in battery performance and production costs. If batteries costs continue to fall and carmakers can offer higher-range BEVs at a competitive price, buyers may be more likely to choose a BEV over a PHEV. An automaker that offers EREV models will likely be able to make the switch to BEVs much easier than a manufacturer producing only parallel PHEVs.

Policies need to account for real-world performance

Regulators and government incentive programs need to be focused on the real-world performance of PHEVs, regardless of the technology or design. Policymakers should assume that parallel PHEVs will largely operate as a gasoline vehicle when considering the climate changing emissions and tailpipe air pollution production, unless there is clear data to refute this assumption from real-world usage. And when EREVs come to market, governments should consider prioritizing EREVs over parallel PHEVs in both regulations and incentive programs. Battery electric vehicles have the most value in reducing emissions, but long-range EREVs could be helpful in the short run to help move drivers from gasoline to electricity.

Bottom line

All-electric BEVs are by far the cleanest option. Nearly 6 million BEVs have been sold in the US through the end of 2025, and a growing charging network and new models should help keep interest in these vehicles. These all-electric vehicles are already a good choice for many drivers and households today. But options like PHEVs, or the EREVs on the horizon, might be attractive options for some households, especially for single car households and those unsure of their charging options.

But it’s important to know that today’s parallel PHEVs are much more similar to a gasoline vehicle than a battery electric vehicle, both in their performance and emissions, while future EREVs have some promise in being a transition to the fully electric future that is needed to reduce air pollution and slow climate change.