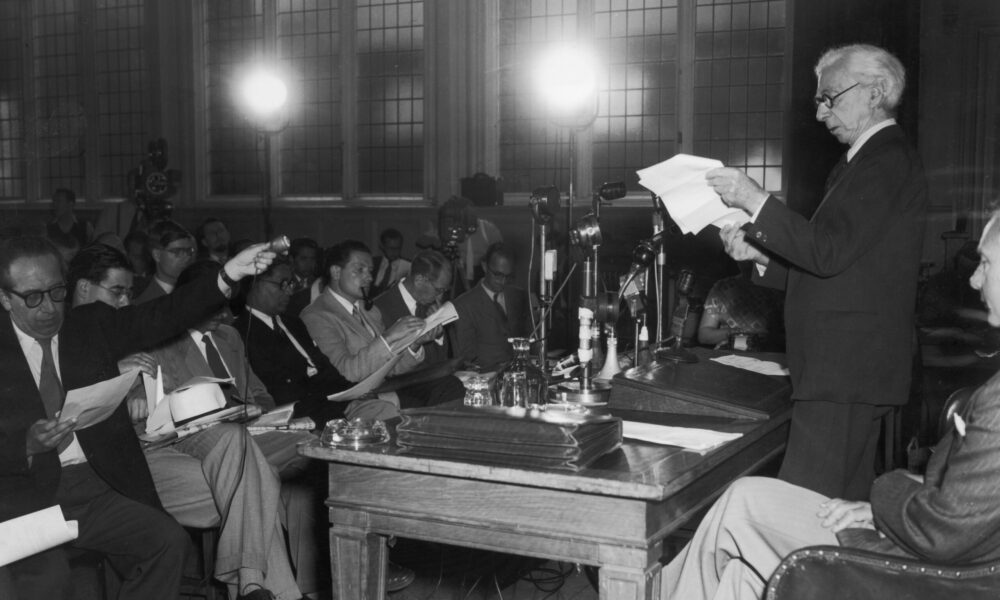

On July 9, 1955, philosopher Bertrand Russell stood before an audience at Caxton Hall in Westminster, London, and delivered a brief but stark ultimatum: humanity must renounce war or face the risk of “universal death.”

This declaration, now known as the Russell-Einstein manifesto, was co-signed by 10 of the world’s most prominent scientists and Nobel laureates, including Albert Einstein—whose signature was his final public act before his death.

The impetus for their statement was a world that Russell feared was in grave peril. The manifesto was a warning to a world at a tipping point.

By 1955, there were three nuclear-armed nations: the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The United States and the Soviet Union had demonstrated the first thermonuclear weapons (or “hydrogen bombs”)—weapons whose destructive potential vastly eclipsed the type that had devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki 10 years earlier. The emerging nuclear arms race was entering a dangerous new chapter and the global polarization between Communist and anti-Communist alliances, Russell intoned, left the world perched at a precarious decision point. The manifesto was a plea—not to any individual head of state or organization, but to humankind, to “remember your humanity, and forget the rest,” lest the future of civilization end in ruinous conflict.

“Here, then, is the problem which we present to you, stark and dreadful and inescapable: Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war? There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge, and wisdom. Shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels? We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.”

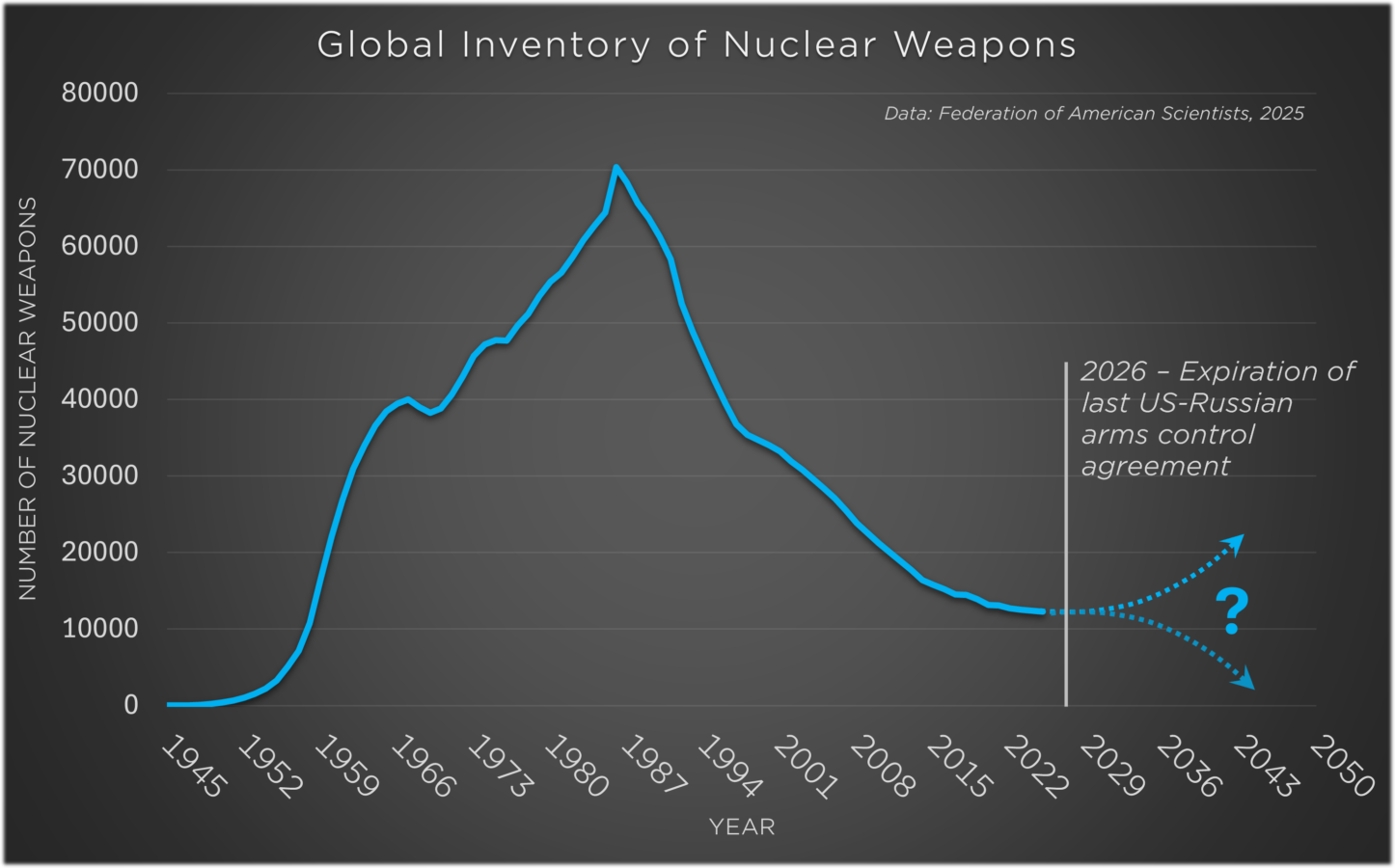

Seventy years on, the world today is drastically different than the tense, postwar landscape of 1955. Even so, the Russell-Einstein manifesto remains alarmingly relevant, perhaps even more so than when it was first delivered. The world has not retreated from making war; although landmark arms control treaties have constrained biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons, nations have continued to marshal their economic and intellectual resources toward building more and new types of weapons.

As nations, including the United States, retreat from democracy and as authoritarian governments take hold, isolationist policies threaten the fabric of longstanding international alliances. Today, there are nine nuclear-armed states, all of which have engaged in military conflict in the past 12 months, either directly or by providing support for ongoing conflicts. This has included direct military engagement between India and Pakistan in Kashmir, the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, and Israel’s war in Gaza and subsequent attacks on Iran with involvement by the United States.

Today’s nuclear arsenals are undergoing modernization to improve their precision, performance, and range. Autonomous weapons, drone warfare, and cyber-risks are evolving in parallel, creating what the US government euphemistically refers to as an “evolving threat environment.”

The dangers identified by Russell and his colleagues have not disappeared; instead, they have multiplied and become more complex. Despite this, the central messages contained in the Russell-Einstein manifesto continue to resonate and offer lessons for re-thinking our path forward to overcome today’s global turmoil.

Going Beyond Arms Control

The manifesto made clear that a truly secure future required complete renunciation of war. While arms control agreements that stipulated quantities or conditions of use for thermonuclear weapons might be useful, the authors warned that agreements written in ink during peacetime can easily dissolve in the fog of war and could easily be ignored. Such agreements, they argued, were bound to be insufficient. Instead, they identified the purpose of the manifesto as calling for a “new way of thinking” that would render future wars impossible.

“We have to learn to think in a new way. We have to learn to ask ourselves, not what steps can be taken to give military victory to whatever group we prefer, for there no longer are such steps; the question we have to ask ourselves is: what steps can be taken to prevent a military contest of which the issue must be disastrous to all parties?”

Understanding the Consequences of Nuclear War

The manifesto also raised profound concerns about the potential environmental and humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons use.

“The general public, and even many men in positions of authority, have not realized what would be involved in a war with nuclear bombs. . . . We have found that the men who know most are the most gloomy.”

Images from the aftermath of Hiroshima were initially suppressed by the US government but a 1946 New Yorker article by John Hersey described the graphic aftermath of the bombings to a wide audience. As horrific images from Japan trickled into the public psyche, awareness of the potential for devastation grew. The health and environmental consequences of nuclear fallout became clearer in the wake of the Castle Bravo test at Bikini Atoll in 1954. Castle Bravo exploded with more than 1,000 times the yield of the bombs used in Japan, spreading fallout over a population of more than 10,000 people in the the Marshall islands and poisoning the crew of a Japanese fishing vessel, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (“Lucky Dragon No. 5”).

Today, we know much more about potential outcomes of nuclear use. Studies have predicted that even a “limited” nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan could disrupt the climate enough to reduce agricultural output in China by up to 21% over the ensuing four years. Modeling has shown that an attack on US ballistic missile silos could spread fallout over most of the continental United States. Nuclear use would almost undoubtedly cripple global supply chains, reduce or eliminate regional agricultural output, and lead to mass starvation and economic collapse far beyond the immediate blast zones. In such a scenario, Nikita Khrushchev once warned, “the living would envy the dead.”

The manifesto expresses the concern that neither governments nor the public fully understood the true consequences of nuclear use. Either through genuine or willful ignorance, this remains largely true today. As Russell said, “What perhaps impedes understanding of the situation more than anything else is that the term ‘mankind’ feels vague and abstract. People scarcely realize in imagination that the danger is to themselves and their children and their grandchildren, and not only to a dimly apprehended humanity.”

Appealing to Universal Humanity

Perhaps most notable, both in its time as well as in its relevance to today, was the Russell-Einstein manifesto’s appeal to all people, not to heads of state or international organizations, but to humanity as a species:

“We shall try to say no single word which should appeal to one group rather than to another. All, equally, are in peril, and, if the peril is understood, there is hope that they may collectively avert it.”

In a world hurtling towards polarization over Communism, the authors implored that our survival as a species was incumbent on our ability to overcome our perceived differences, despite our natural tendencies towards preservation of identity, whether national, racial, or ethnic.

“Most of us are not neutral in feeling, but, as human beings, we have to remember that, if the issues between East and West are to be decided in any manner that can give any possible satisfaction to anybody, whether Communist or anti-Communist, whether Asian or European or American, whether White or Black, then these issues must not be decided by war.”

In a 1959 interview with the BBC, when asked what wisdom he wished to pass along to future generations, Russell distilled this to its very essence, stating, “Love is wise, hatred is foolish”—a moral that can hardly be simplified but which seems increasingly disconnected from today’s social divisions and hyper-nationalist tendencies.

The Legacy of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto

Despite its brevity and apparent simplicity, the immediate impact of the Russell-Einstein manifesto was significant. The document is widely credited with inspiring one of the most consequential Cold War conferences of scientists, the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs. The first meeting was convened in 1957 in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, by Joseph Rotblat, one of the manifesto’s co-signers and the only physicist to have withdrawn from the Manhattan Project on moral grounds. A series of conferences followed, bringing together scientists from both sides of the Iron Curtain to work towards reducing the risk of armed conflict and finding solutions to global security threats. Rotblat was awarded the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize for starting the Pugwash movement to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons.

Decades later, the manifesto’s call for “new thinking” strongly influenced Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), which helped to end the Cold War and paved the way for landmark arms control agreements that reduced global nuclear arsenals significantly.

The question posed by the Russell-Einstein manifesto remains as urgent as ever: Will we choose the path of “continual progress in happiness, knowledge, and wisdom,” or “shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels?” The answer may come from Russell’s philosophical predecessor and sometimes intellectual opponent George Santayana, who said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Whether through fear or wisdom, the world learned hard lessons from the Cold War and was able to achieve sweeping arms control agreements and dramatically pull back from the competition of the US-Soviet arms race. Today, we stand at another perilous crossroads. The choice, as in 1955, is ours to make.