“The pompous villager thinks his hometown is the whole world. As long as he can stay on as mayor, humiliate the rival who stole his sweetheart, and watch his nest egg grow in its strongbox, he believes the universe is in good order.…”

“Cree el aldeano vanidoso que el mundo entero es su aldea, y con tal que él quede de alcalde, o le mortifique al rival que le quitó la novia, o le crezcan en la alcancía los ahorros, ya da por bueno el orden universal….”

–José Martí, Nuestra América, 1891

In the first few weeks of 2026, President Trump’s actions have thrown the Western Hemisphere into turmoil and dangerous uncertainty on a scale not seen for a long time. The abduction of both President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores in Venezuela violated domestic and international laws: The military incursion was carried out without Congress’ knowledge or approval as required by the War Powers Resolution, and in violation of the United Nations’ charter and the core principles of the Organization of American States.

The Trump administration claimed that President Maduro is the leader of an international drug trafficking ring with the colorful name Cartel de los Soles, a made-up organization. Its name was inspired by the sun-shaped medals that Venezuelan generals wear in their uniforms. The pretense was recently dropped during the initial indictment of Maduro on drug trafficking charges, as the US Department of Justice backed off from what was long thought to be a dubious claim—turns out the Cartel de los Soles is not an actual organization, but a slang term for what the United States says are corrupt military leaders in the South American country. In fact, an analysis of drug trade data from the UN’s Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) found that Venezuela is not a prominent supplier of cocaine or fentanyl to the United States.

The goal in Venezuela was never democracy or stopping the narcotics trade

With the pretense gone of removing President Maduro for leading a drug trafficking organization, and Venezuela’s role proven very small in exporting narcotics to the United States, the real motivation behind the Trump administration’s illegal and destabilizing incursion and abduction quickly became clear. Seizing the vast fossil fuel and mineral resources of Venezuela is the naked and unabashed goal of President Trump and the fossil fuel industry that supports him.

And perhaps in a nod to MAGA nostalgia, the administration has harkened to a relic from the 19th century: the Monroe Doctrine, a claim making a useful comeback for the Trump administration’s re-energized imperial ambitions. Many observers have begun calling the new US approach “the Donroe Doctrine”—a term that appeared on a January cover of The New York Post—a Trumpian twist on a 19th-century idea.

Quick history lesson: The Monroe Doctrine posits the Western Hemisphere as the natural area of the globe where the United States is entitled (by divine right according to the long-standing influential ideology of Manifest Destiny) to exert complete control and influence, other nations be damned.

Said another way: The Monroe Doctrine is the white supremacy of Manifest Destiny turned into hemispherical foreign policy. And in our current global context, that doctrine is now being used to justify an incursion, a kidnapping, and the theft of oil resources that do not belong to the United States. What the administration isn’t saying is that control over Venezuela’s government and oil also seeks to reduce the rising influence of China and Russia in Latin America, and to curb Latin American administrations that do not bow down to the president’s designs.

America and Nuestra América are not the same thing

The hemispherical arrogance of American exceptionalism is embedded even in that colloquial and geographically inaccurate euphemism for the United States: America. This exercise in naming is profoundly political and encapsulates the role of civilizer that the United States has historically reserved for itself in the continent.

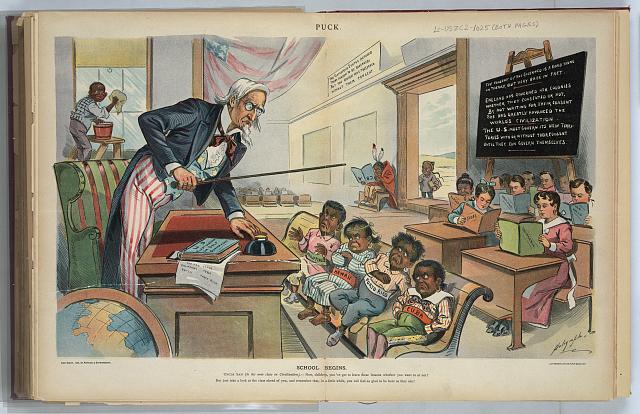

An 1899 cartoon in the political commentary magazine Puck visually summarizes this view in very offensive and racist ways. The then newly acquired territories of the Philippines and Puerto Rico, plus Cuba and Hawaiʻi are depicted as unkempt and grotesque adult-faced children under the tutelage of a menacing and imposing teacher—Uncle Sam. The recently-acquired states or territories (Arizona, Alaska, California, New Mexico, and Texas) are depicted as white schoolchildren diligently reading their lessons in civilization. The scene is completed with offensive representations of African Americans as the janitorial help, a confused Native American student sitting in the back trying and failing to learn his ABCs, and an Asian student in the “Chinaman” racist trope, outside the classroom, completely excluded from learning.

Though this cartoon contains only two Caribbean nations, it conveys the thinking that shaped US foreign policy in Latin America in the name of US national security and geopolitical interests over three centuries. And that thinking has returned under the Trump administration, but without the civilizing nor spreading democracy pretenses of past interventions in Cuba, El Salvador, Chile, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, to name a few. The Trump administration’s self-serving, aggressive, and individualistic vision for Latin America—as expressed directly by Secretary of State Marco Rubio, “This is OUR hemisphere,” immediately after the Venezuela incursion—could not be further from the pan-Americanist vision that emerged in the 19th century among Latin American leaders and thinkers of a liberated continent, in the words of the great Cuban national hero José Martí: Nuestra América.

In Martí’s vision of Nuestra América, nuestra or “our” does not mean the United States, but rather refers to all the nations of the Western Hemisphere that would co-exist in peace, prioritizing the social, economic, political prosperity, and well-being of all, without hegemonic powers (at that time he meant neither European colonizers nor the United States) ruling over other nations.

Sounds utopian, unattainable, pie-in-the-sky? Maybe. But he, along with millions of Latin Americans for centuries, have not been wrong to push back on the inherent paternalism of the Monroe Doctrine.

Latin American leaders are not background characters

A more equitable Nuestra América based on collaboration, cooperation, and dialogue is possible. This is what the leaders of the two largest Latin American economies—Claudia Sheinbaum in México and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brasil, are advocating for. Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro has rejected both the Venezuela incursion and President Trump’s threats against Colombia and Petro himself. While most US media frames issues by repeating the latest quote-worthy braggadocio to come from the president’s mouth, Sheinbaum and Lula have been the adults in the room, urging a return to non-interventionist collaboration and dialogue in a context of respect for the national sovereignty and territorial integrity of Latin American nations. This is in line with both countries’ longstanding principles of non-intervention in other countries’ domestic affairs.

In response to the tacit or explicit threats that Trump has issued against México, Sheinbaum recently declared: “It is necessary to reaffirm that in México the people rule, and that we are a free and sovereign country—cooperation, yes; subordination and intervention, no.” And Lula said of the raid in Venezuela: “These acts represent a grave affront to Venezuela’s sovereignty and yet another extremely dangerous precedent for the entire international community.”

Oil wars and interventionism are bad for regional stability and the global climate

What’s different today compared to Martí’s time is that the United States’ current interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine and other expressions of US global power are driven by its unrelenting desire for fossil fuel capitalism and control of fossil fuel deposits, rare earth minerals, and other resources.

But as my colleague Kathy Mulvey just wrote, betting on Big Oil is a losing proposition, as adding more oil to an oversupplied global market will not be profitable in the short term, will worsen the lives of Venezuelans, hurt the bottom line of US taxpayers, and be detrimental to an already unstable global climate. Venezuela’s “extra heavy” oil requires a lot of energy to heat it up and bring it to the surface, increasing the potential for high emissions just from extraction and processing. In addition, millions of Venezuelans already have been displaced by the social, economic, and climate crises in their country. If conditions there worsen due to a climate disaster or a full-blown military incursion by the United States it could result in an increase in displacement to neighboring countries such as Perú, México and Colombia which have already absorbed millions of displaced Venezuelans.

The intervention in Venezuela and the abduction of Maduro also must be seen as a dangerously desperate attempt by an unsustainable administration to deflect attention from its internal crises (e.g., dismantlement of the federal government, Epstein, healthcare, cost-of-living, federal immigration crackdowns, and political repression at home).

The United States is not above international or domestic laws

Regardless of the United States’ brazenly renewed imperial ambitions—now with the added threat of annexation to Greenland in addition to the Venezuela incursion—we live in a world of international and domestic laws. In the United States, Congress and all sectors of society need to demand a return to the domestic and international rule of law regarding the territorial integrity of all countries in the Western Hemisphere. A narrowly-defined hemisphere in the service of the geopolitical interests of the Trump administration and its fossil fuel allies leaves out nearly one billion people who live outside of the United States. And the choices made by the United States have put the planet on a path dependent on accelerating global warming and the global and regional wars for control of those resources.

A different world, not based on the Trump administration’s repulsive notion that might is right, is possible.