Whether in a city or a small town, we all want to get to where we need to go. We want more transportation options that reduce household and public costs, we want economically thriving communities, and we want our families and loved ones to be healthy. The Massachusetts Freedom to Move Act (S.2246/H.3726) would support all those things and more—filling a necessary gap between the state’s climate goals and the transportation decisions it makes regularly. Specifically, this state bill:

- Ensures state and regional transportation plans reduce pollution and provide more options like transit, walking, and biking.

- Sets goals to reduce the need to drive, aligned with statewide climate targets.

- Establishes an intergovernmental coordinating council to oversee progress.

From Pittsfield to Provincetown, people are struggling with high transportation costs

People across Massachusetts are feeling the squeeze – two recent MassINC polls showed that 19% of people in the state reported transportation costs as a “very big” burden and over one-in-three people (36%) in Massachusetts experience some level of transportation insecurity, where people cannot leave the house or they miss appointments due to transportation issues. This is apparent in the data – the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s Housing + Transportation Index shows that around 57% of people in Massachusetts are living with unaffordable housing and transportation costs, and vehicles cost the state over $64 billion every year in consumer and public costs.

Often underrecognized are Massachusetts’ rural areas, where a scarcity of public transit and the need to traverse larger distances between places can leave folks without any other options besides needing to own a car. Indeed, 30% of people living in Massachusetts’ rural communities report that transportation costs are a “very big” burden, far higher than their suburban or urban counterparts. In addition, 38% of rural Bay Staters reported not being able to leave the house due to transportation problems more than sometimes, also higher than their suburban or urban counterparts.

This situation is especially acute when considering Massachusetts’ rural areas’ demographics. Massachusetts’ rural areas have 13% more people over the age of 65 than the rest of the state, of which nationally 18% do not drive. Compared to urban areas, rural areas also have more people with disabilities, who give up driving at rates up to 25%. Research has shown that this lack of mobility results in social isolation and poor health outcomes. So while over 30% of people across the state do not drive—whether that is due to age, disability, unaffordability, or something else—not being able to drive in a rural area has particularly severe impacts.

The Freedom to Move Act will help ensure that the transportation system works for everyone in the state. It ensures that harmful projects like highway expansions are balanced out by a variety of potential mitigation measures, such as investment in rural transit services that are lifelines for those who need it, or smarter small town planning so people in rural areas do not have to travel as far to get to the doctor or grocery store. The lack of affordable options affects rural communities the most, and this bill would help alleviate those burdens. Investing in more transportation options is also crucial for the climate.

Driving away from state climate targets

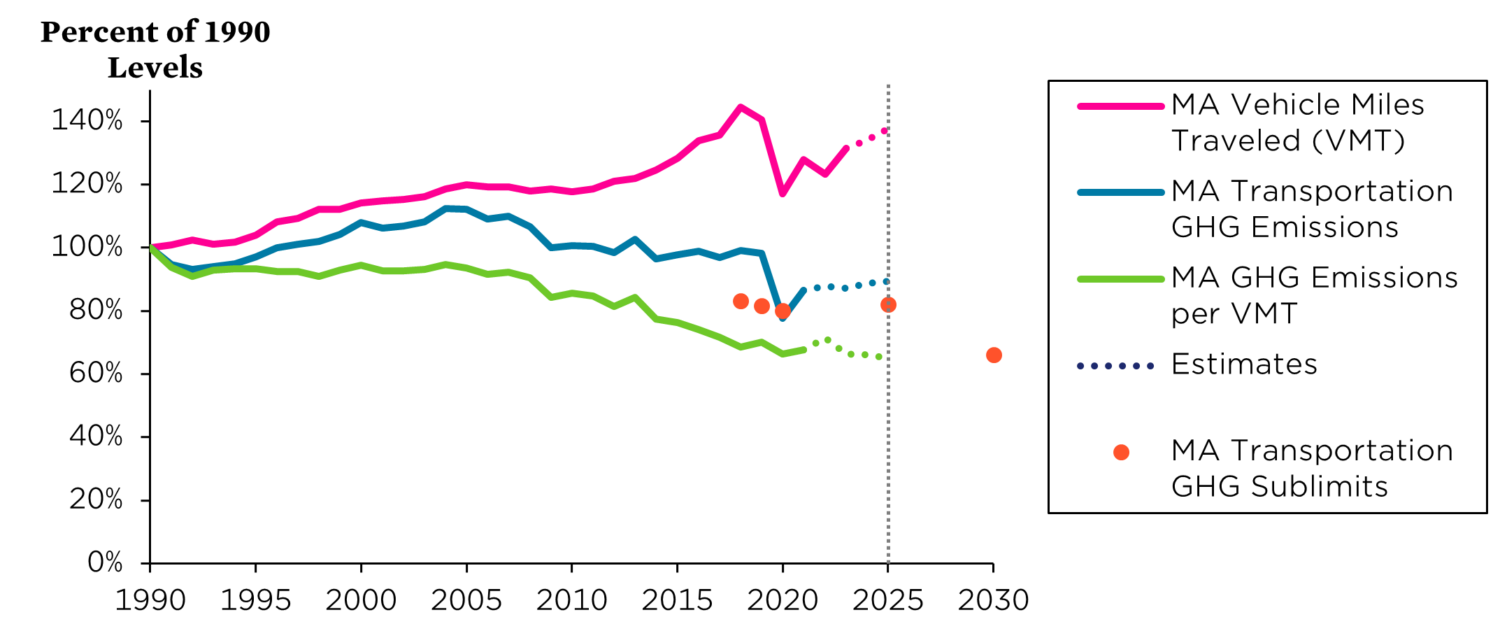

Transportation has been the biggest sector contributing to climate change in Massachusetts practically every year since the earliest emissions inventory for 1990 and most recently has contributed 38% of state greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2021. So, it makes sense that the state set specific sublimits and specific strategies for transportation emissions in trying to meet its overall target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Shortly after the state set its climate targets, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) stepped up—with the “GreenDOT Policy Directive” in 2010 affirming MassDOT’s role in reducing global warming emissions. Initial climate plans included ambitious goals to increase transportation options and reduce the need to drive via transportation investments and smart growth. Through subsequent regulation adopted in 2015, the state took the lead in the country by requiring metropolitan planning organizations and MassDOT to evaluate the emissions impacts of transportation projects, which you can now see in state transportation plans. Yet, while MassDOT’s State Transportation Improvement Plans since then have all predicted slight statewide GHG reductions, driving per capita grew around 4 times faster after 2015 than it did in the 25 years prior.

In 2016, the landmark decision in Kain v. Department of Environmental Protection found that the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) was not doing enough to attain the “actual, measurable, and permanent emissions reductions” of the state climate law. And so, in response, MassDEP introduced six regulations to show they mean business, one of which set ambitious transportation sector emissions limits for 2018, 2019, and 2020 in line with top-line climate goals. The catch – these limits were not enforceable, and the state quietly blew past them in 2018 and 2019.

Fast forward to 2021. The widely-celebrated climate law required new sector-level limits that were much closer to being legally enforceable. The next year, the state’s climate homework was due, and turns out, it passed—the state met its 2020 emissions limit. But progress in transportation was on shaky ground. The state was only able to meet its overall goals because of the drastic reduction in driving during the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic. If transportation sector emissions remained constant from 2019, the state would likely have exceeded the legally binding limit, triggering legal enforcement.

Now, the most recent 2021 data exceeds the 2025 transportation sublimit by 6%, and is on track for further increases in the following years. While data is not complete yet for the years since, estimates using state gas tax receipts show that the state is on track to exceed the Clean Energy and Climate Plan (CECP) 2025 sublimit by 9% in 2025. While electric vehicle adoption has taken off and is a key part of the state’s long-term climate strategy, the state’s increases in driving since 2020 put it on track to not meet future CECP sublimits.

VMT, aka a Voracious Money Trap

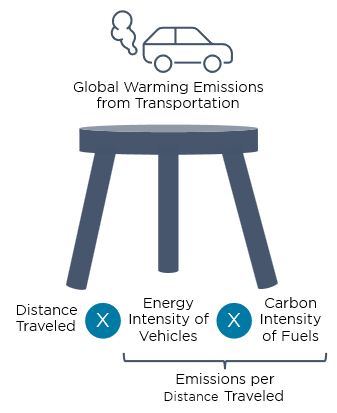

Transportation’s climate emissions rest on a three-legged stool: how much we drive, how much energy our vehicles use to drive, and the emissions associated with that energy. While the country and Massachusetts have made significant improvements over the last few decades in making every mile we drive cleaner, these are in constant tension with the ever-increasing amount that we drive. As the CECP recognizes, the state requires both electrification and providing alternatives to personal vehicles to comprehensively tackle the problem of transportation emissions. Our recent report Freedom to Move goes further—and shows how providing more transportation options actually can make transportation electrification more feasible, reducing necessary energy infrastructure buildout and battery mineral demand.

The measure of how much we drive to get where we need to go is called vehicle miles traveled (VMT). More VMT generally means more emissions, paying more for fuel and transportation costs, and spending more time on the road. The measure is decreasingly linked to economic growth, as more sectors of the economy do not depend on travel, and communities expand, causing sprawling infrastructure to become an expensive liability to public budgets. Higher VMT is also a poor indicator of people meeting their needs—i.e. driving more to reach the same places can be a waste of time and money. In the end, people in the US drive significantly more than in other countries, largely due to sprawl and car-oriented infrastructure, and making different decisions about what we built can help change our trajectory.

The missing piece: the Freedom to Move Act

Massachusetts is currently off track for its transportation emission targets, and the Freedom to Move Act can help get the state back on rails. Despite the clear call from advocates across the state, currently there is nothing requiring MassDOT and MPOs to make decisions that set the state up for success, only soft asks to consider emissions in decision-making. Setting statewide vehicle miles traveled reduction goals, linking those goals to transportation sector sublimits, and establishing an intergovernmental coordinating council to create a plan and report on progress is the way to show the state means business.

The Freedom to Move Act fills these gaps—and that’s why your state legislators need to hear from you to support this crucial piece of legislation to get the state back on track.