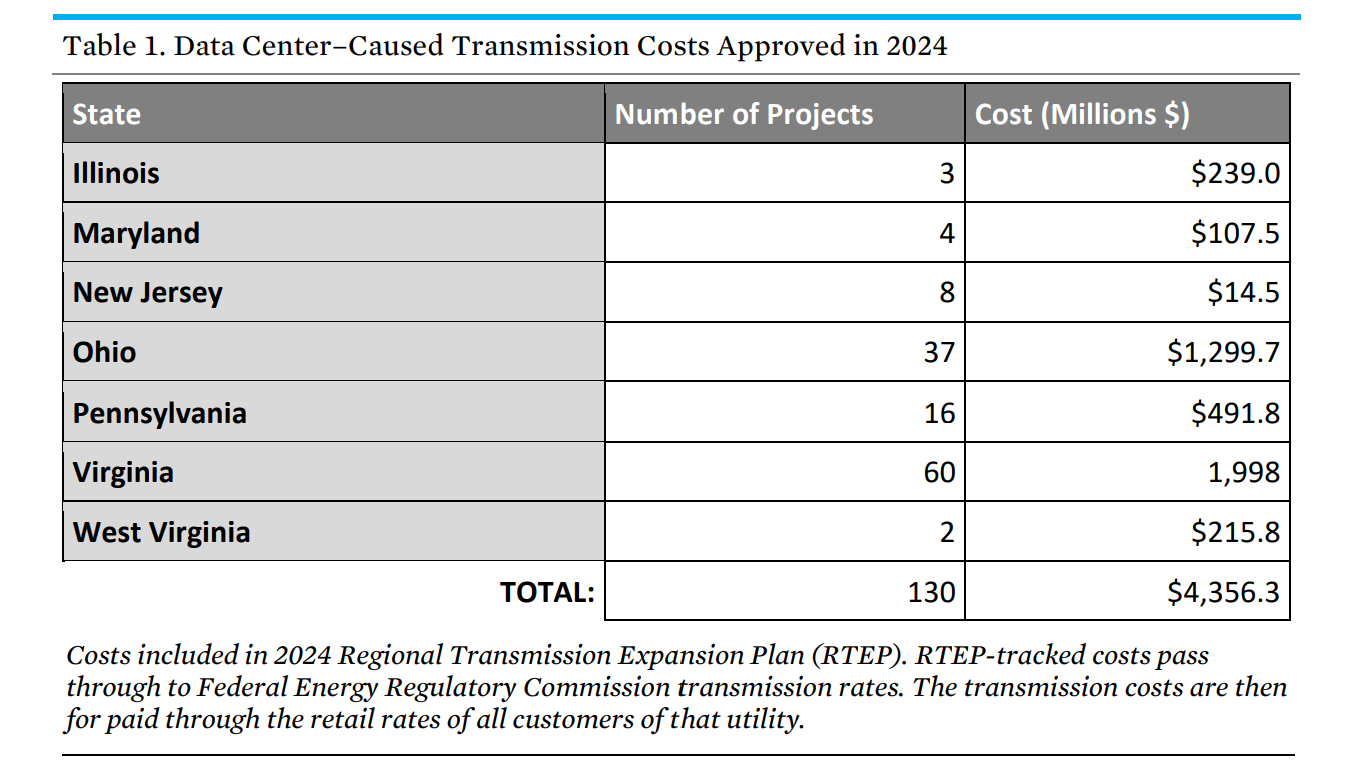

Electric bills are going up around the country and some of those increases are due to an outdated practice that requires consumers to pay billions for tech giants’ grid connections. Our new analysis tallies up $4.3 billion in costs in 2024 for just seven states: Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia.

This problem stems from the jaw-dropping, unprecedented size of the electric demands of new data centers. Many data centers built recently have the electricity demand of small cities. New proposals for data center campuses have power demands comparable to the total power plants in small states.

Through a review of planning documents across states within the grid operator PJM’s jurisdiction, I found 130 examples of electric utilities connecting data centers to the grid with very expensive new lines while passing costs to consumers under old rules. From most perspectives, this is morally wrong and bad policy. However, from the perspective of the rules for electric companies making routine expansions of their transmission and distribution wires, this is standard practice.

I have a lot of respect for what the utility industry does to keep the lights on, but this is a case where the old proverb “With great power comes great responsibility” must be applied. The regulation of utility monopolies should provide affordable and reliable service for consumers and predictable terms and conditions for the utility business. The data center boom is a historic business opportunity for the electric sector, and utility companies are aware consumers are already facing risks as a result.

Utilities’ feeble reforms

Around the country, consumers are alarmed by rising utility bills while utilities are responding with insufficient changes to ensure that the large new data center customers are held responsible for simply paying their own bills. While the explosion in electric demand from data centers is leading to new spending for power supplies (covered widely by the media ) and costs for the wires to connect the data centers (subject of my new analysis), the flurry of reforms aim to set minimum commitments from the data centers to put up deposits and ensure that they will pay their bills for 10-15 years.

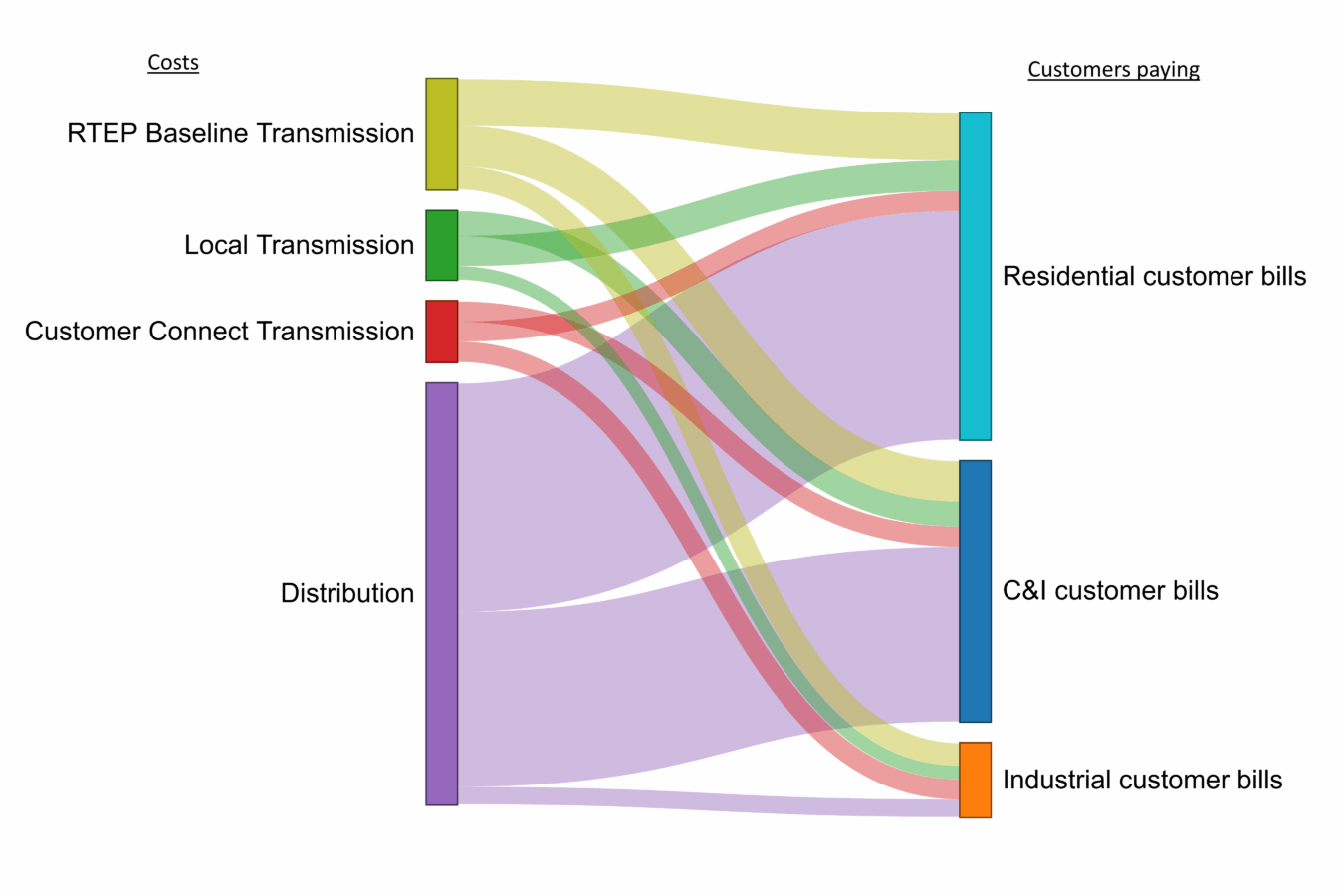

These reforms do not change who pays for the new costs. The costs for both the new power plants and the transmission—even the wires to the data centers’ buildings—are paid for collectively by all the customers of the respective host utilities. Rates set by state and federal regulators have not adapted to costs caused solely by very large customers. The current practice assigns costs with outdated assumptions, illustrated in the graph below, with wires costs on the left side and customers paying on the right. The new costs from large customers’ transmission-level connections is shown in red.

What are we paying for?

Totaling $4.3 billion in 2024 alone, the costs for the electric connections that extend from the existing transmission lines to the data center customers are immense. These are costs for directly connecting the data centers, often including new transformers and gear on the property of the data center. Many of these individual connections cost between $25 million and $100 million. The one-year totals for seven states are shown in Table 1 below.

I’ll show you what I found.

Utilities in the PJM regional transmission organization provide a brief look at the transmission they are planning for local needs, which includes improvements for customer service as well as replacing old equipment. For example, one transmission upgrade in Maryland, just north of the Virginia border, is shown in the two utility company slides below. (Other utilities plans can be found here.)

This slide shows the need identified by the utility, which has a tracking number, marked with arrow at top. The lower arrow points to the description of a single customer that wants to use 300 MW (a city’s worth of demand), and they want it available as soon as possible.

Source: First Energy

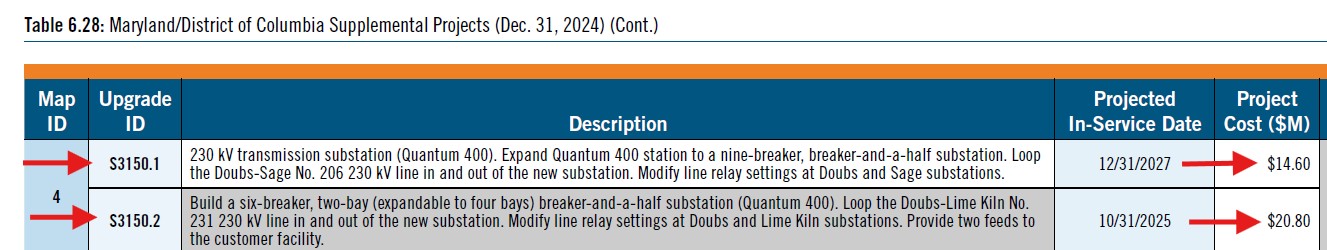

In the second slide, the utility describes how it will meet this need. The tracking number at the top is the same, and I have circled in yellow the drawing of the single new customer. Lower on the slide are descriptions of the investment the utility will make for this customer, with costs of $20.8 million plus an additional $14.6 million, and new tracking numbers for the construction of these facilities. Those tracking numbers, s3150.1 and s3150.2, will show up in the PJM Regional Transmission Expansion Plan as “Supplemental Projects.”

The notoriety of the local plan

When these data center direct connections are included in the utility’s locally planned transmission plans, they become part of the regional transmission expansion plan without regulatory review. In addition, this step also allows the utility to include the costs in transmission rates. This sequence of essentially automatic approvals has caused controversy and calls for reform, even before the rise of data center costs.

While the PJM process described here is more transparent than in many states and regions, every utility has the means to develop new transmission to connect new customers. This is a central function for electric companies. What is new here is the enormous size of these new customers and the eye-popping costs that their connections require. The size of these customers requires connection of these individual customers to the transmission system, a scenario not routinely anticipated by the rules for assigning costs to customers that cause those costs.

A $4 billion loophole that gets bigger each year

Because of a gap in regulatory jurisdictions, the transmission costs are bundled together, filed at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), and then sent to the states as one amalgamated cost. The information describing the cause of certain costs as due to a single customer is lost. The rules for customers are generally set by the states, while the rules at FERC are only applied to wholesale customers and not meant to apply to retail customers.

When these enormous new customers arrived in recent years, their costs were allocated without respect for the principle of cost causation. Usually, regulatory decisions aim to assign costs to the entities that cause those costs. This problem needs to be fixed. Early indications for the coming year reveal $2.5 billion for more data center connections in these seven states so far, and dozens more in progress.

Follow the money

The utility process for putting transmission costs onto customers’ bills follows from the regional expansion plan, as shown below. The two projects shown with red arrows are the same projects as shown above, with the tracking numbers on the left and the costs on the right. This is an excerpt from PJM’s 2024 Regional Transmission Expansion Plan reflecting the utility’s local plans.

When the annual costs for this utility’s transmission system are calculated, any costs in the Regional Transmission Expansion Plan are included, even these customer connection costs. That amalgamated cost number is carried over to the rates presented for customers bills at the state utility commission. The costs for transmission are spread to all of the utility’s customers, as illustrated by the graph of money flows above.

This spreading of costs isn’t illegal. It is simply out of date. Unfortunately the impact is very real. The wealthiest companies are building extraordinarily expensive data centers that you and I are subsidizing. Our policy brief walks through this problem and provides recommendations for several ways to assign the new costs to the customers that cause those costs. That is a responsibility of the rate-setting utility commissions. Our policy brief shows where to find the evidence needed to make this change. We are taking this argument to the regulators and telling everyone: data centers can pay for their own needs.

The brief can be found here. The accompanying appendix can be found here.