EDITORIAL UPDATE (11/13/25): A more recent version of the analysis in this blog is available here.

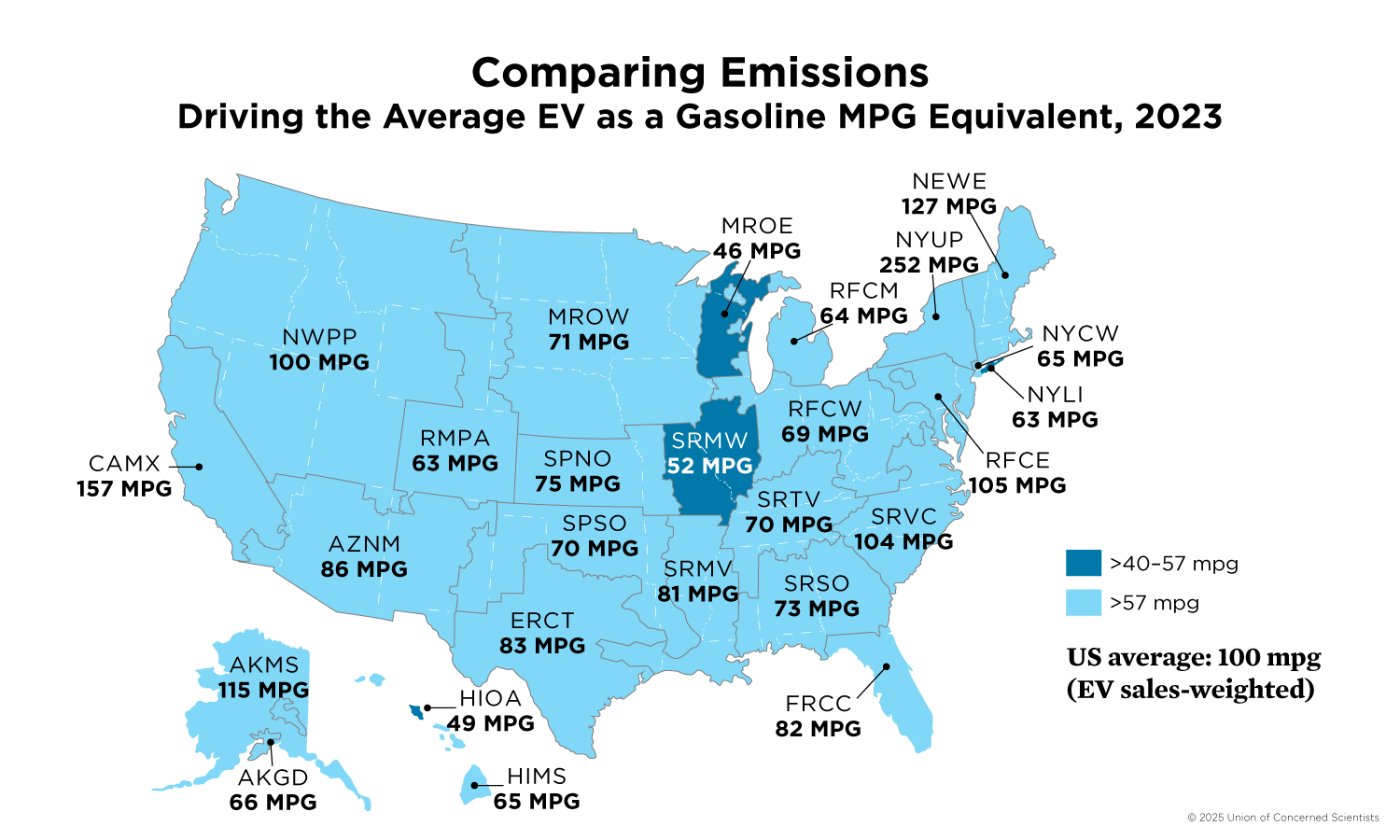

There is tremendous uncertainty about what policies the federal government will change that will affect electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing and sales in the US. But there is no question about the impact that EVs will have on reducing climate-changing emissions. Replacing gasoline with electricity greatly reduces the carbon emissions from driving, even when emissions from mining, manufacturing, and generating electricity are included. Based on where EVs have been sold, driving the average electric vehicle in the US produces global warming emissions equal to a hypothetical 100 mile per gallon gasoline car, or one fourth the emissions from driving the average new gasoline vehicle.

Transportation is the largest sector for emissions and passenger cars, trucks, and SUVs are the majority of emissions from this sector, so there is no way to slow down climate change without a fundamental shift from petroleum to clean electricity to power our vehicles.

Driving the average EV in the US produces carbon dioxide emissions equivalent to a hypothetical 100 mpg gasoline car.

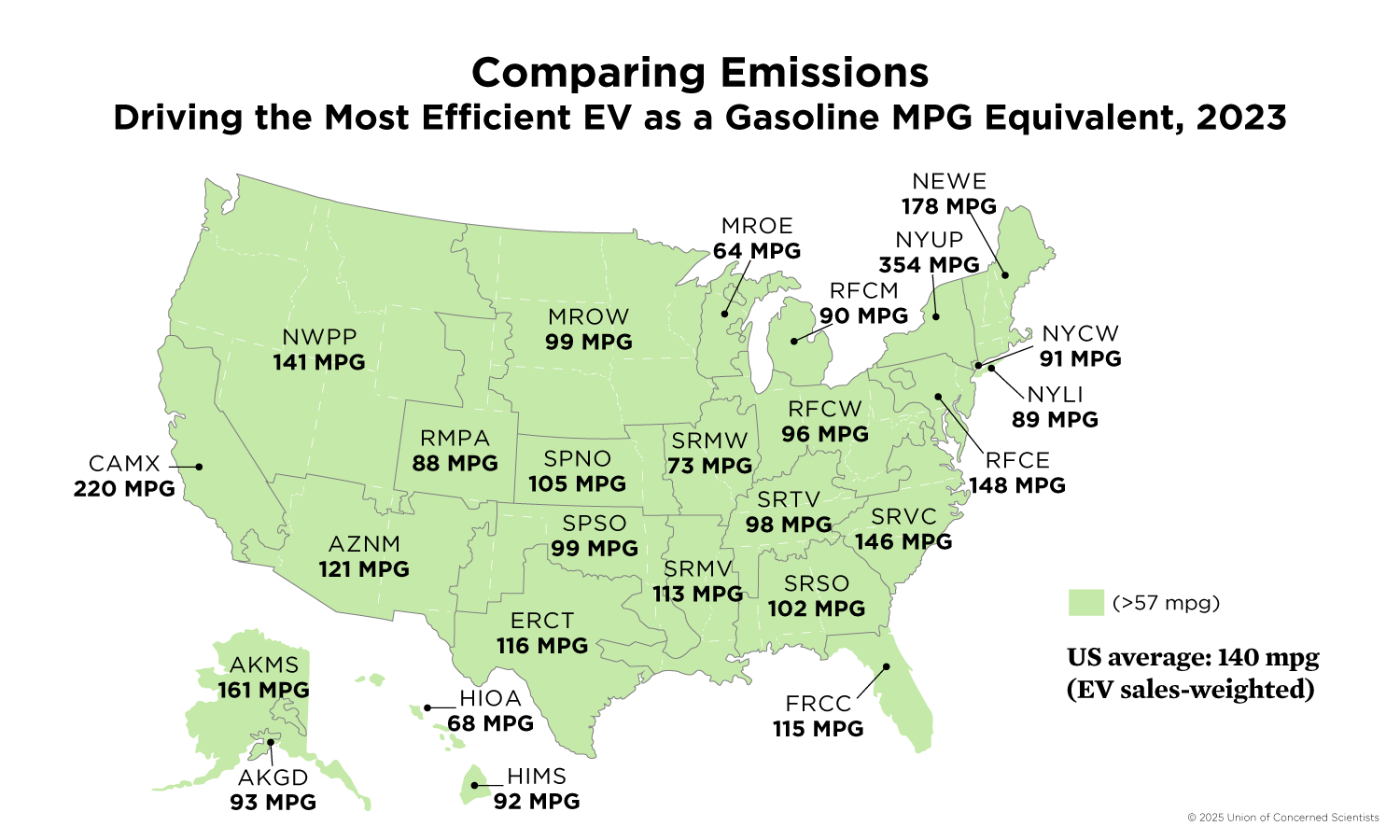

When UCS first compared driving an EV to a gasoline car, only 45 percent of the country lived where driving an EV had lower climate-changing emissions than a 50 MPG gasoline car. Now, 97 percent of the country lives where the average EV is better than the most efficient gasoline vehicle (57 mpg). And for everyone in the US, driving the most efficient EV produces less global warming emissions than any gasoline-only vehicle available (including non-plug-in hybrids).

These results are based on the most recent electricity emissions data available from the US EPA. Released earlier this year, the data reflects actual powerplant emissions for 2023. As our electricity grid switches to more renewable sources of electricity, the climate benefits of switching from gasoline to electricity will continue to grow.

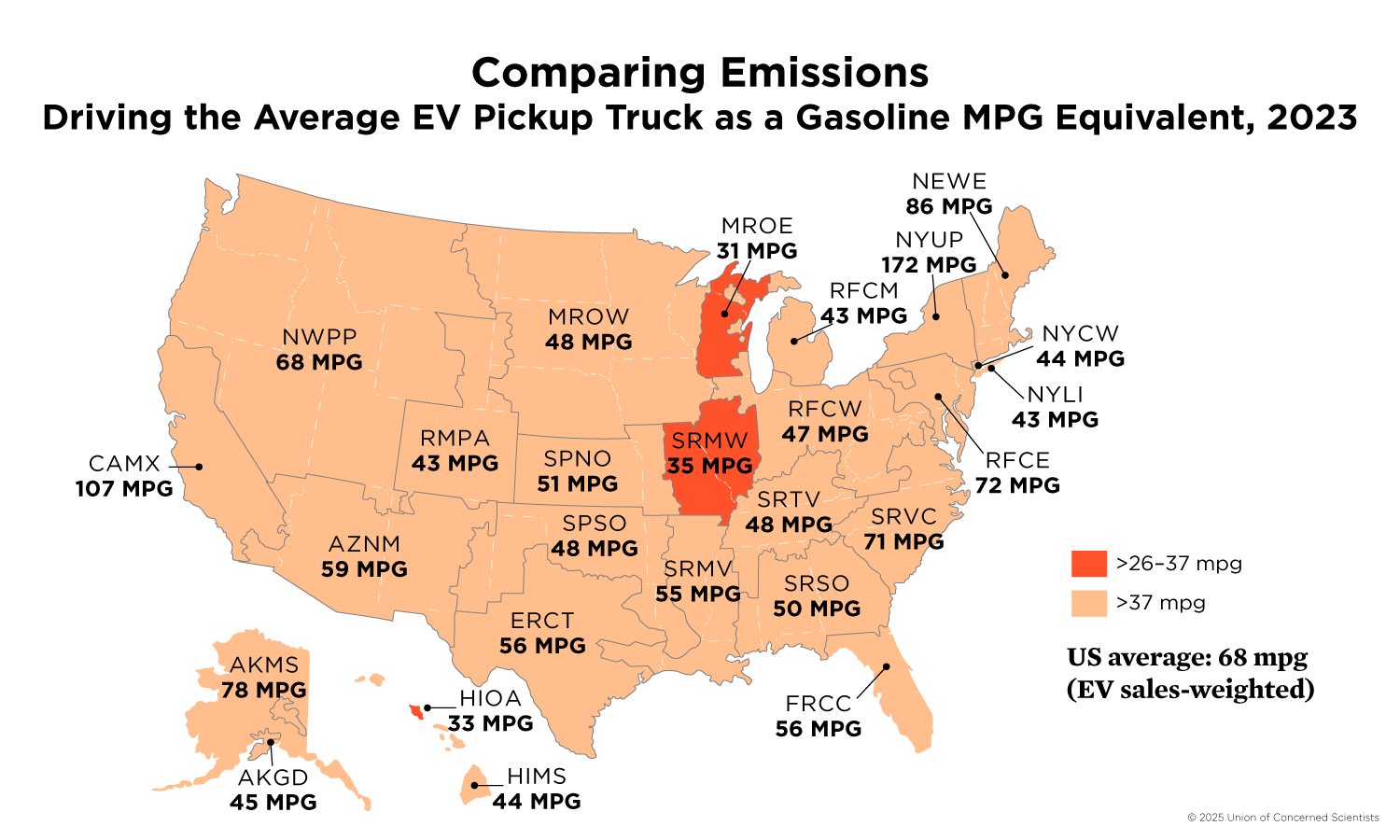

EV emissions depend on source of electricity

The emissions from driving an EV depends on where the electricity comes from to recharge it, and that depends on where in the country you’re recharging. In places with a relatively clean grid, emissions from driving an EV are very low. For example, driving an EV in upstate NY is equal to a 354 mpg gasoline car, or less than 7 percent of the average new gasoline vehicle emissions.

Even where the grid still has significant fossil fuel-powered generation, EVs are a cleaner choice. In the grid region that serves most of Texas, driving the average EV produces emissions equal to an 83 mpg gasoline car, despite over 60% of electricity generation coming from fossil fuels.

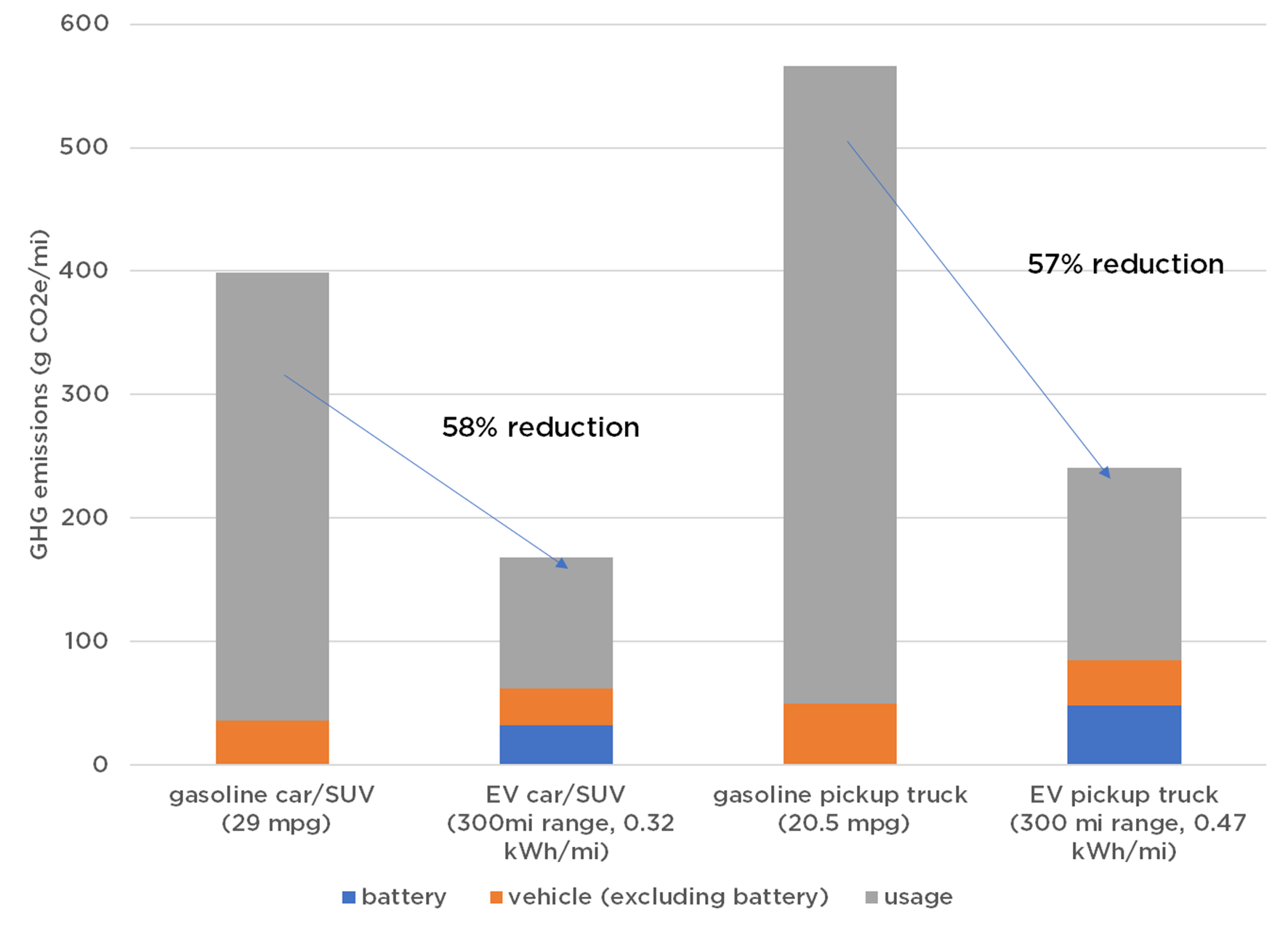

EVs are responsible for less than half the global warming pollution of gasoline cars, even when including emissions from manufacturing

Manufacturing an EV results in more global warming emissions than manufacturing a comparable gasoline vehicle. This is chiefly due to the energy and materials required to produce an EV’s battery. However, most of the global warming emissions over the lifespan of today’s vehicles occur during use, so the reductions from driving an EV more than offset the higher manufacturing emissions. When comparing the average gasoline car and 2-wheel drive SUV (29 mpg) to the average-efficiency EV with a 300-mile-range battery, the EV reduces total lifetime emissions 58 percent, and an EV pickup truck reduces lifetime emissions 57 percent compared with the average gasoline pickup.

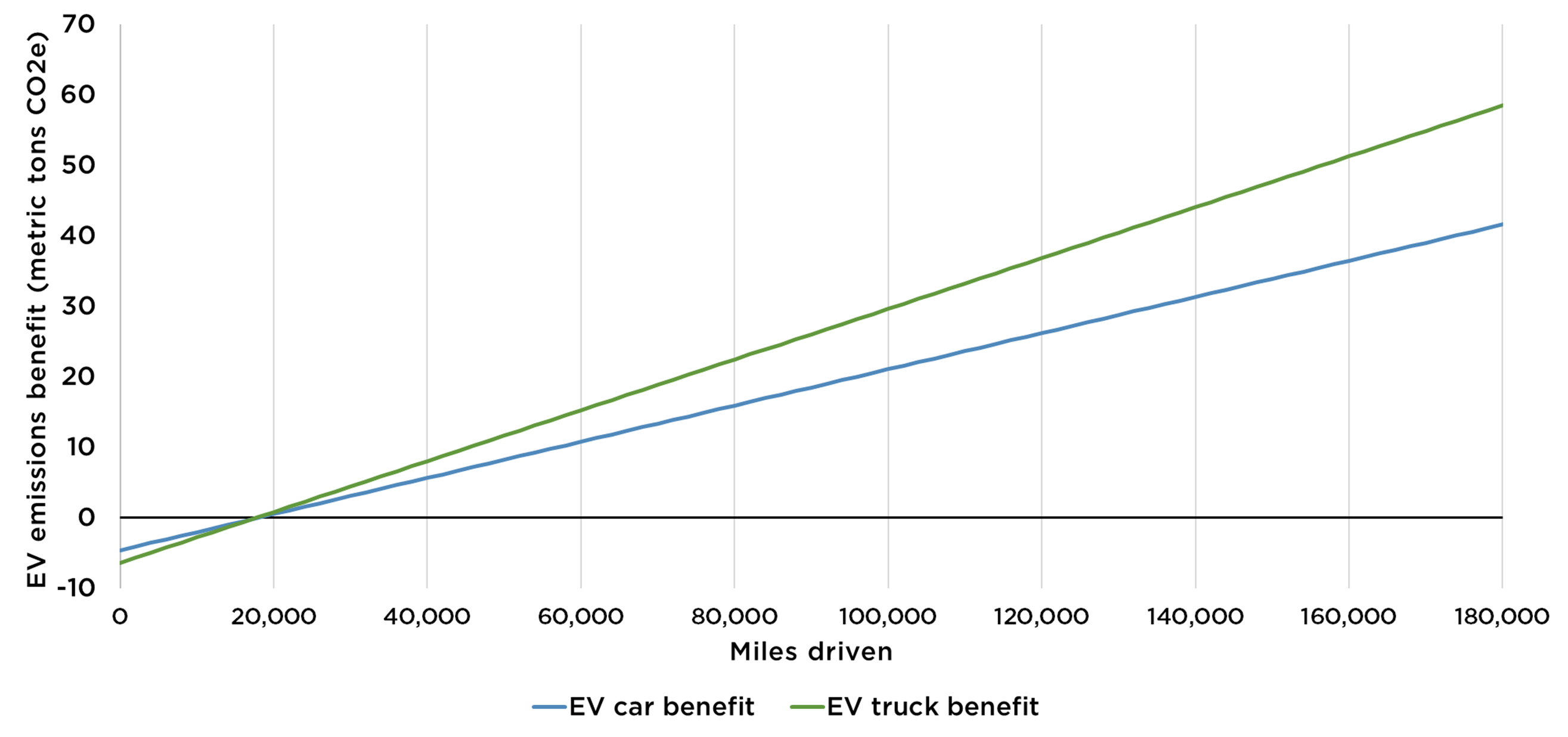

Another way to understand how emissions savings from driving an EV offset additional manufacturing emissions is to consider the breakeven point: how far or how long an EV needs to drive for the savings to match the initial emissions “debt.” Based on the average electricity emissions for recharging EVs sold in the US, the breakeven point for an electric car with a 300-mile range compared with the average new gasoline car is about 18,000 miles of driving or less than 2 years, based on average annual driving. Breakeven occurs more quickly, after about 17,700 miles, when comparing an electric truck with a 300-mile range with the average new gasoline pickup truck.

For both cars and pickups, net savings come early in an EV’s lifetime, and most EVs would yield significant net emissions savings. After 150,000 miles of driving, the average EV car would result in 34 metric tons of avoided carbon dioxide emissions and the average EV pickup truck in 48 metric tons, compared to manufacturing and driving a comparable gasoline vehicle.

Choosing a more efficient EV can offset charging on dirtier power

EVs vary in efficiency, with the most efficient EVs going more than 4 miles on one kilowatt-hour of electricity while some electric pickup trucks get less than 2 miles of driving on the same amount of energy. Choosing a more efficient EV that meets your driving needs will reduce the emissions from driving. For example, charging the average EV on Florida’s grid means effective emissions equal to 82 mpg in a gasoline car, while choosing an EV like the Lucid Air can reduce emissions to that of a 115 mpg conventional vehicle. And of course, a more efficient EV will also cost less to recharge.

Electrifying larger vehicles like pickups can also reduce emissions

Using an electric pickup truck in the place of a gasoline truck can have clear emissions benefits; on the grid that covers most of Texas, using an average electric pickup truck can have emissions lower than a 2025 Toyota Prius XLE (52 mpg). However, switching from an efficient gasoline car to an electric truck means reducing or eliminating the climate benefit of electrification. Drivers that are looking to lower their emissions and fuel bill should choose electric vehicles over gasoline vehicles but also choose the most efficient vehicle that meets their transportation needs.

Emissions from electricity generation (and for using EVs) have dropped dramatically

The first UCS analysis of the emissions from EV driving in 2012 showed promise for EVs, but the emissions for some parts of the country were equal to the efficient non-hybrid gasoline cars of the time. In the 2012 analysis, only 45% of the country lived where driving an EV was better than a 50 MPG gasoline car. In this most recent analysis, that number has skyrocketed to 97% of the country living where the average EV is better than the most efficient gasoline vehicle (57 mpg). And for everyone in the US, driving the most efficient EV produces less global warming emissions than any gasoline-only vehicle available (including non-plug-in hybrids).

Driving on electricity is better, for trips that require a car

Switching from gasoline to electricity means significant reductions in climate-changing emissions and this transition is a necessary step to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. But the emissions savings from not driving altogether are even higher. Replacing driving with public transit or e-bikes can greatly reduce emissions. And walking or using a traditional bike means avoiding air pollution and climate-changing emissions altogether. With our current transportation system, it’s difficult for many people to switch all their trips to transit, walking, or biking, but using these modes even part of the time can make a positive difference in the pollution from personal transportation.

Notes on calculations

The analysis presented in this blog uses the methods detailed in the 2022 report “Driving Cleaner”, with the following modifications:

- The data source for electricity generation was updated to EPA’s eGRID2023 data (released in January 2025).

- Upstream emissions factors now use the GREET2024 database from Argonne National Laboratory.

- Small-scale solar (residential and commercial) that is not included in eGRID has been estimated using the state-level data from the Energy Information Agency’s Electric Power Monthly (table 1.17B) report and allocated to grid subregions using population-weighted averages based on EPA’s ZIP code subregion assignments.

- The average EV efficiency and location of EV sales (for the sales-weighted national emissions estimate) has been updated to reflect EV sales from 2015 through 2024 based on data from Atlas Public Policy.

- The manufacturing emissions now use GREET2024 and reflect a 95kWh battery for car/SUV EVs and 140kWh battery for EV pickup trucks. The emissions assume that batteries for EVs have the following battery types (as defined in GREET2024): 9% NMC111, 7% NMC532, 4% NMC622, 8% NMC811, 63% NCA, and 9% LFP.