After Israel’s attacks on Iranian nuclear sites, nuclear scientists, and military leaders on June 13, the world briefly inched even closer to the precipice of another disastrous war in the Middle East. Despite the announcement of a ceasefire on June 23, questions remain about its durability, as well as about the fate of Iran’s nuclear sites, its highly enriched uranium, and whether it will seek nuclear weapons or remain a party to the Non-Proliferation Treaty. For now, the world holds its breath and hopes that this de-escalation will hold.

How does China fit into all this? Beijing’s response is representative of its foreign policy overall: seeking to leverage ties with both sides of the conflict in order to play a mediating role. The United States and its allies should consider that China’s role presents more of an opportunity than a threat.

In that regard, the trend in the United States of casting China as the head of an anti-western “axis” including Iran, North Korea, and Russia is an oversimplification. China certainly makes political and strategic choices when it comes to foreign policy; it has chosen to align itself more with Russia against Ukraine and with Iran against Israel. However, these ties have limits, and it tries to maintain diplomatic relations with all sides. It does not enter conflicts directly or provide military support.

The common thread through China’s approach to current conflicts, from Korea to Iran to Ukraine, is its opposition to third-party intervention: China is critical of US and NATO military support for Ukraine, of the US bombing of Iran, and of the US role in, as China sees it, complicating relations between North and South Korea. The limits it places on its own security ties and its criticism of US alliances show a strong aversion to security obligations.

Stability as Foreign Policy

China has increasingly pushed for a role as an international mediator and has continually stressed the importance of international institutions like the United Nations, while also working to build its own organizations with a greater focus on Global South nations. Despite political ties to anti-NATO/US countries, it is clearly striving to occupy a role in the middle. Though some might criticize this as naked opportunism, the United States and its allies should see it as an opportunity. China’s goal of maximizing connections to both sides of conflicts allows it to play a role as a go-between. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s calls for China to prevent Iran from closing the Strait of Hormuz and President Trump’s comment that seemingly accepted China’s continued buying of Iranian oil both suggest a recognition and acceptance of this role from Washington’s side.

This approach, prioritizing stability, is also evident in China’s strained bilateral relationship with the United States. Through multiple rounds of trade wars and tariffs initiated by Washington, China has always displayed a willingness to return to the table and play ball.

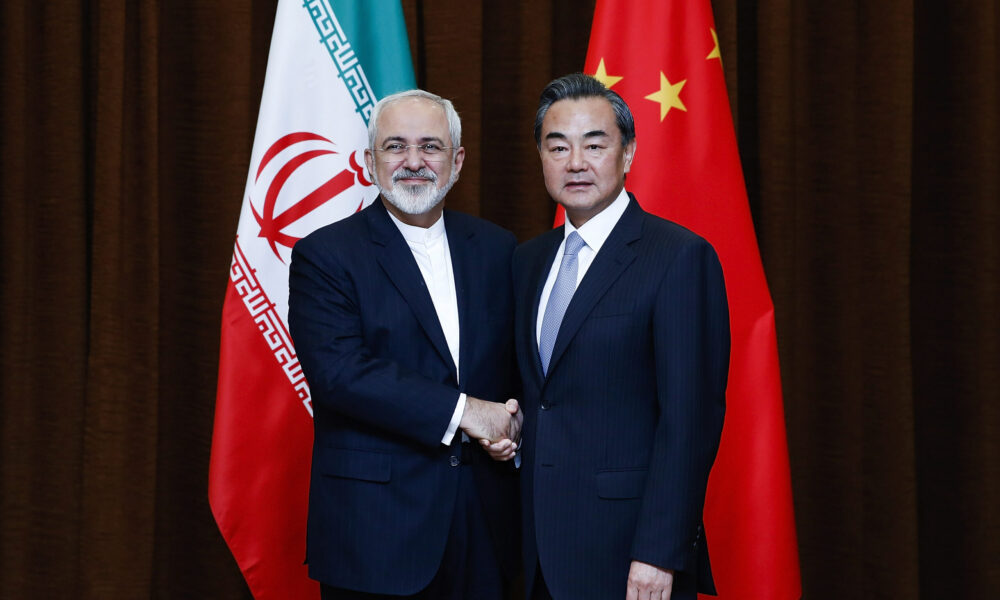

And while its relations with Israel have generally been positive, Beijing’s approach has been dynamic since the war in Gaza began. Before Israel’s strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities, China was seeking to thaw a bilateral relationship with Israel that had become frosty since the destruction in Gaza intensified. Now, its harsh condemnations of Israeli and US actions in Iran suggest that thaw might be reversed, or at least paused, though China is also unlikely to provide direct support to Iran beyond advocating for a sustained ceasefire.

The Oil Must Flow

China will, however, continue to play its most important role in economic support of Iran. Estimates vary, but the most widely cited estimate suggests that China buys nearly 90% of Iran’s oil exports, making up about 14% of China’s total oil imports. This economic support is key for Iran, similar to how Chinese imports from and exports to Russia have been crucial since its economic ties to most of Europe and the United States were dramatically reduced after the war in Ukraine began.

This dynamic is a central indicator of how China approaches these situations. While it maintains close ties with both parties, it avoids direct alignment with either side through, for example, weapons sales. Despite multiple US accusations of such, China does not sell weapons to Russia, though it does sell components that Russia needs to manufacture its own.

China’s focus on mediation aligns with this approach. It brokered a surprising normalization of relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia in 2023, has consistently tried to present a framework for peace in Ukraine, and recently founded the Hong Kong-based International Organization for Mediation, a body intended to help countries resolve disputes outside the adjudication-based international courts. This focus on compromise makes sense because China wants to maximize its relations on all sides; it has close ties with the Saudis and the Iranians, and significant economic ties to Ukraine while being politically close to Russia. The greater the bilateral stability between these parties, the more China stands to gain.

While Beijing likely wants to position itself similarly between Israel and Iran, the United States emboldened Israel to use illegal force and supported Israel through direct military involvement, which tips the scales and makes it hard for China to maintain its balancing act.

Taking on a More Vocal Role?

With that in mind, Chinese comments on the US bombings of Iranian nuclear sites show an adherence to noninvolvement, while also suggesting a slight shift in its approach once the United States became directly involved. On June 23, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) condemned the US bombings of sites under international supervision, saying that the UN Security Council “cannot avoid getting involved.” On June 14, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi had already said that the targeting of nuclear sites sets a “dangerous precedent.”

Also, on June 13, an MFA spokesperson was asked whether China would support Iran’s closing of the Strait of Hormuz, which Iran had threatened to do if it were attacked. At the time, the spokesperson said he “would not comment on hypothetical situations.” However, after the US attacks on June 23, the spokesperson was willing to at least acknowledge the strait’s importance to international trade, calling on all regional parties to de-escalate the situation in order to avoid spillover effects to the global community. Beyond condemnations, China’s Ambassador to the UN Fu Cong commented that the United States had not only harmed international law and nuclear nonproliferation efforts, but had also torpedoed its credibility as an international negotiator.

These responses suggest three things. First, China still wants to take a strong stand against nuclear risks globally. After Russia made nuclear threats against Ukraine, Beijing issued a strong rebuke, recognizing the unique risks of attacks targeting nuclear sites, as well as the harm they cause to global nonproliferation. Also, Beijing has become increasingly concerned about pre-emptive conventional strikes on its own nuclear arsenal, with many experts citing growing US capabilities in that area as a potential driver of China’s own nuclear expansion. This is probably at least part of the “dangerous precedent” Wang Yi mentioned.

Second, direct US involvement in striking Iran has probably pushed China to pivot toward Iran’s side. While China gets approximately half its oil through the Strait of Hormuz, the Chinese response did not call on Iran to refrain from closing the strait but rather called for all actors to de-escalate. This suggests that China at least understands Iran’s rationale should it decide to close the strait. This is especially noteworthy considering Secretary of State Rubio’s explicit call on China to help prevent a closure. China is probably worried about the potential economic impacts, but some sources have suggested that it might be better able to weather that storm than other countries. The language from the MFA suggests that a public call for Iran to refrain from closing the strait is unlikely, though work behind the scenes is more likely.

Finally, Fu Cong’s comment on US credibility touches on China’s desire to present itself as a more balanced, responsible superpower when it comes to negotiation and mediation. To be clear, China does not prefer a United States that is unreliable as a negotiator and cavalier about using military force abroad. However, it will be happy to play a greater role if US influence atrophies.

Ready to Fill a US Vacuum

Influence is really the name of the game. What Washington sees as an anti-US bloc is really Chinese willingness to play ball with states on the outside or periphery of the international community. The “axis of evil” rhetoric has more to do with a US desire for other countries—allies and beyond—to minimize Chinese influence. However, even Israel, the US ally with perhaps the most influence in Washington, maintains economic ties to China and does not go along with US requests to cut them out.

Also, Rubio’s calls for Chinese help with the Strait of Hormuz show the strategic benefit to the world of China positioning itself in a pragmatic middleman role. Was Rubio trying to shift blame onto China in case a closure did happen? Possibly, but either way this is still a concession of Chinese diplomatic clout. That clout will only grow if the United States continues to prioritize tariffs and bombs over diplomacy.