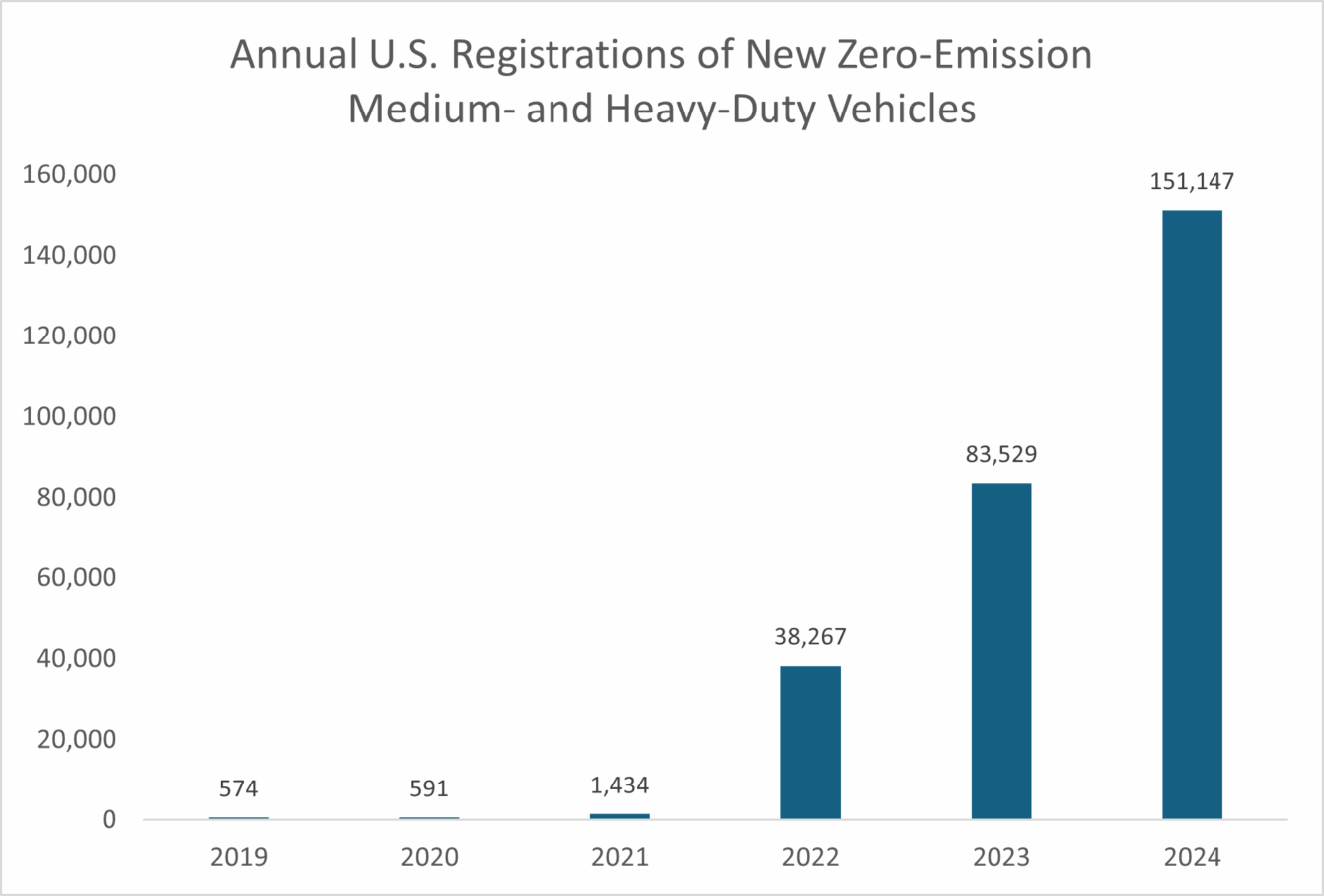

Thanks in large part to state and federal regulations and programs spurring record deployments of electric trucks and billions of dollars in truck charging station investemtns nationwide, the past few years have delivered much progress toward a cleaner, modern, and more energy-efficient freight system. Between 2020 and 2024, the share of zero-emission models among new registrations of medium- and heavy-duty trucks, vans, and buses grew from around 0.04 percent to nearly 10 percent. In California, zero-emission models made up over one-quarter of all medium- and heavy-duty vehicle deployments in 2024.

Unfortunately, this meaningful progress has faced momentous setbacks this year, with the upcoming repeal of California’s Advanced Clean Fleets Rule in response to threats from the Trump administration, the demise of federal incentives for zero-emission trucks in the budget bill, a nationwide disinformation campaign by truck manufacturers to undo electrification progress, and Congressional attempts to undo California’s half-century-old prerogative to set vehicle pollution standards (like the Advanced Clean Trucks Rule) by revoking waivers previously approved by EPA.

These seemingly never-ending backsteps have jeopardized our nation’s progress toward a modern freight system that’s less harmful to public health and the planet. Thankfully, California and other states leading the push have many opportunities to continue this important work without the approval from the federal government. In June, California Governor Gavin Newsom did just this through an executive order, directing state agencies to find new ways to meet the state’s zero-emission transportation goals. Additionally, ten other states have joined California to create the Affordable Clean Cars Coalition to maintain momentum toward a clean transportation system.

Amid lapsed federal leadership, it is more crucial than ever for states to drive our nation toward a sustainable freight system that is more globally competitive and less susceptible to fluctuations in oil prices from geopolitical conflicts. Now is the time for states to step up – here are a few ways they can.

Developing zero-emission ecosystems around freight hubs

Focusing electrification efforts and investments at freight hubs – like seaports, railyards, and warehouses – is key to both reducing pollution in the communities struggling the most with poor air quality and fostering widescale truck electrification. Over two-thirds of the total freight tonnage shipped within the United States occurs on the back of trucks (more than all other transportation methods combined) and the journey for much of the goods shipped begins and ends at freight hubs. In the absence of concerted and strategic federal leadership toward a sustainable freight system, focusing electrification efforts at freight hubs creates a durable foundation for wider progress.

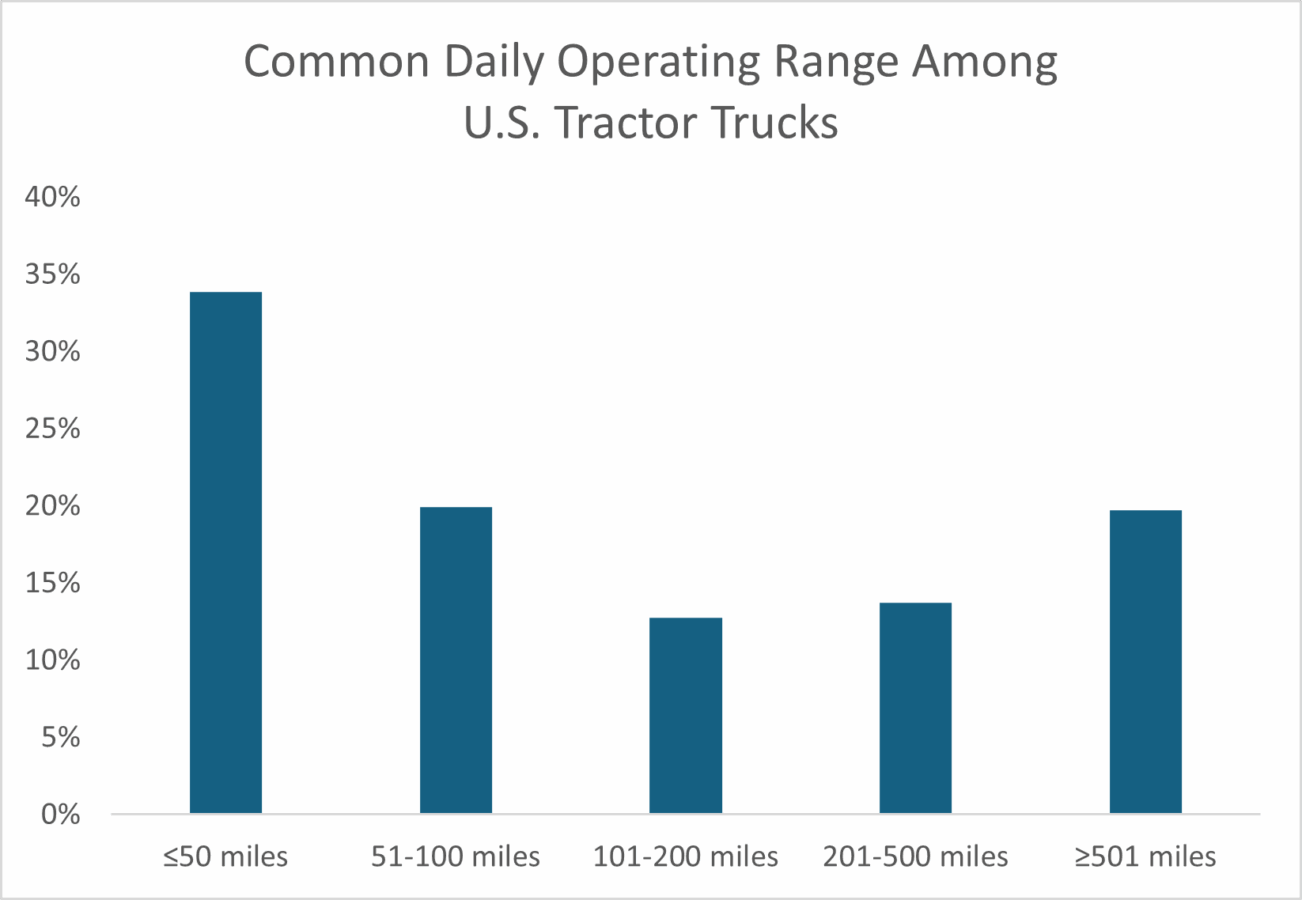

Ports are not only hubs for commerce and goods movement but are also hot spots for diesel pollution. Around 40 million shipping containers passed through US ports in 2024 alone, most of which made their way to and from the ports on the back of a diesel-powered semi-truck. Many of these first and last trips between ports and warehouses, known as drayage runs, occur over short or regional distances. In fact, over two-thirds of semi-trucks nationally travel less than 200 miles daily – well within the range of electric tractor truck models available today.

Deploying electric trucks at freight hubs will help to address air pollution in adjacent communities while also creating strong market signals for wider investments in truck charging infrastructure. Today, truck charging stations are both operational and under development in and around California’s major ports from Oakland to San Diego. The growing number of truck charging stations supporting container movement to and from ports is an excellent foundation on which to develop a wider, hub-based network of charging stations.

States, local governments, and port authorities have a suite of impactful policy tools at their disposal to help accelerate electrified drayage, reducing harmful air pollution while delivering meaningful economic benefits to fleet operators and businesses. A number of these policies, such as Indirect Source Rules, de minimis fees on container movement and last-mile deliveries, and queuing preferences for zero-emission trucks, are in place today. More novel policies and programs, such as low and zero-emission zones and app-based software for truck drivers that integrate scheduling for drayage and truck charging could also help to expand zero-emission truck deployments.

Indirect Source Rules

Indirect Source Rules (ISRs) are an emerging strategy to reduce high concentrations of air pollution in and around freight hubs. Rather than regulating pollution from smokestacks or vehicle tailpipes, ISRs take a systems-based approach to addressing pollution from the operations associated with warehouses, seaports, railyards, and other freight hubs. Importantly, state and local ISRs do not require approval from the federal government.

Freight facilities covered under ISRs are required to reduce pollution associated with the activities that they facilitate or attract—such as truck trips, ship and locomotive visits, container handling equipment or other associated sources of pollution. Facilities can choose from a menu of flexible actions and strategies to meet their specific requirements under an ISR. These could include installing truck charging stations at loading docks or elsewhere on-site, installing solar panels, and purchasing zero-emission trucks and cargo handling equipment. In lieu of these actions, facilities may be able to pay a mitigation fee, but fees are often the least-used compliance pathway in existing ISRs, which is further evidence of the program’s flexible compliance design.

Southern California’s Warehouse ISR, initially implemented in 2022, has shown significant results in accelerating zero-emission and less-polluting operations. During the first several years of the program, zero-emission truck visits to facilities covered by the ISR nearly tripled, usage of electric truck chargers increased by over 20-fold, and on-site solar power generation at warehouses increased from under three gigawatt hours to over 85 gigawatt hours.

Container and cargo fees

Small fees levied for shipping containers and cargo carried to and from freight hubs by fossil-fueled trucks can help accelerate electric truck adoption by generating steady and significant revenue streams for programs that provide electric truck incentives and investments in charging infrastructure.

In 2022, the Port of Los Angeles and Port of Long Beach implemented a $10 per container fee specific to the two ports that funds projects and programs supporting electrification efforts, including an electric trucks incentive of up to $100,000 in addition to what is offered under state incentives. To date, the Port of Long Beach has raised over $110 million, supporting the construction of over 100 truck chargers currently in operation (with nearly 120 additional under construction) in the Long Beach harbor district and over $30 million toward electric truck incentives. The Port of Los Angeles has collected over $120 million from the program to support purchase incentives for over 450 electric drayage trucks and funding for eight truck charging stations with over 200 chargers.

A 2020 study estimated container fees to have negligible impacts on freight throughput and drayage trips while generating hundreds of millions of dollars for the Port of Los Angeles and Port of Long Beach. Even at a rate of $70 per container, decreases in drayage truck trips were estimated at 0.5 percent while a $20 per container rate was estimated to decrease truck trips by 0.01 percent. Because container fee programs may exempt zero-emission trucks from the fee, already miniscule impacts to throughput are likely to decline as adoption of zero-emission drayage increases.

While the container fees at the Port of LA and Long Beach were estimated to have limited impacts on throughput, it’s important to consider that fee mechanisms may have varying impacts on ports of different sizes or those that mainly deal with automobile imports and exports, bulk goods, or other non-containerized freight. Because of this, a statewide approach could have more equitable economic benefits and impacts on smaller ports and reduce new sources of intrastate port competition.

Zero-emission fast lanes and software solutions

Several smaller scale programs could also help to increase deployments of zero-emission vehicles at ports, such as zero-emission express lanes and drayage operator software tailored to zero-emission vehicles. These programs may come with lower political or economic hurdles and provide additional upsides to drivers and fleets operating clean trucks.

Lengthy queue times are a common occurrence for drayage trucks entering some ports. At the Port of Tacoma for example, drivers can spend over an hour just waiting to enter the port during peak hours – and this is in addition to the hour or so spent loading freight after they enter the port. Recognizing that time is money, some ports have adopted express lanes for zero-emission trucks to further incentivize their adoption. Especially at ports with lengthy average queue times, express lanes could provide drayage operators with additional flexibility to visit during peak hours and reduce the overall turn time.

Major ports are also turning to software solutions to help reduce queue and turn times for drayage operators. In 2024, the Port of Oakland released a mobile app for drayage operators that provides operators with valuable information related to queue and turn times, vessel schedules, and other resources. Software solutions like Oakland’s could help to promote zero-emission drayage adoption by integrating scheduling for electric truck charging at port terminals with drayage queues. Such functionality would allow an electric drayage truck operator to schedule a charge during periods of long queuing and turn times while keeping their place in the queue – essentially a win-win for the drayage operator to reduce time and staff expenditures.

Low- and zero-emission zones

Although quite uncommon in the United States, low- and zero-emission zones are becoming increasingly common across the globe. These policies can take a variety of shapes, but the central idea is the designation of an area that limits or restricts the operation of fossil-fueled vehicles. Zero-emission zones are a powerful tool for reducing air pollution from transportation in targeted areas.

By focusing specifically on freight vehicles, some political barriers and economic equity concerns may be avoided. Rotterdam, Netherlands, which is home to the largest seaport in Europe, recently implemented a zero-emission freight zone for logistics vehicles that requires commercial delivery vans and tractor trucks operating in the core of the city to be zero-emission vehicles by 2028 and 2030, respectively.

Zero-emission freight zones around key ports, warehouses, and railyards could enhance the feasibility of California meeting its 2035 goal to transition to zero-emission drayage operations statewide, especially in the absence of regulations like the Advanced Clean Fleet Rule. Similar to container and cargo fees, a statewide approach to a zero-emission freigth zone policy would likely achieve the highest environmental and public health benefits while reducing economic barriers and competition among in-state ports. This would allow the program to focus on the areas most impacted by freight pollution while accounting for differences in operations, cargo throughput, and electrification readiness.

Accelerating zero-emission truck sales and infrastructure Deployments

With the repeal of market-driving clean truck incentive programs under the Inflation Reduction Act and the fate of foundational rules like Advanced Clean Trucks left to the courts, expanded state incentive and investment programs are crucial to maintaining the market signals driving freight electrification. Although battery-electric drayage trucks are expected to have the lowest lifetime costs among all fuel types before the end of the decade, upfront costs for most battery-electric truck models remain significantly higher today than their diesel counterparts. Incentives for clean trucks can help to bridge this gap as the market grows and upfront prices for trucks decline. Additionally, targeted state investments in charging infrastructure for electric MHDVs can help to accelerate the much-needed transition to cleaner on-road freight.

Innovative and expanded funding incentives for clean truck purchases and infrastructure investments

Today, California and several other states offer purchase incentives for zero-emission trucks and grants and rebates for zero-emission truck charging infrastructure. California’s program, known as HVIP, is structured to cover the incremental cost of zero-emission truck models compared to analogous models of combustion trucks, offering between $7,500 and $200,000 per truck. California also offers up to $100 million annually for zero-emission truck charging infrastructure.

Given the importance of vehicle incentives and infrastructure deployment to accelerate the early stages of MHDV electrification, the state should explore options to secure sustainable and expanded funding structures for both new and existing programs. One method discussed often today is a revenue-neutral fee program for new combustion MHDVs sold or registered in the state that would fund expanded rebates for clean trucks and infrastructure investments. This approach would provide a significant and sustainable source of revenue – in 2024 alone, nearly 90,000 new Class 2b-8 vehicles were registered in California.

The structure of a fee-based program could take a wide range of approaches, including by applying either to new sales or annual registrations, and by setting the fee amount in relation to vehicle size or weight or by considering the comparative cost of analogous combustion and zero-emission models. Policymakers would also need to consider the scope of vehicles to which the fee applies, and which entities and vehicles are eligible for incentives. There is a strong argument for fees to apply to all MHDVs, including smaller Class 2b-3 vehicles purchased for both private and commercial use. Considering that these vehicles account for around two-thirds of all MHDV sales, including these vehicles in a fee structure could significantly increase programmatic revenues, even at de minimis amounts. Furthermore, because zero-emission Class 2b-3 vehicles have nearly reached upfront cost parity in many cases, significant purchase incentives may not be necessary to advance adoption of these vehicles. This would allow for additional incentive funding for more expensive vehicles like tractor trucks.

Whatever approach policymakers take, the program should be designed to encourage manufacturers to lower upfront costs over time, rather than essentially pocketing the incentive. Previous research has suggested that methods such as including eligibility caps, price ceilings, or “reverse auctions,” which reward manufacturers who employ competitive pricing, could help to achieve this.

Clean delivery fees could raise billions for clean freight initiatives

Another way to generate revenue for zero-emission freight incentive programs is through small fees on last-mile deliveries of products to consumers, including e-commerce and on-demand delivery services. This approach could capitalize on the significant growth in these delivery types while influencing continued growth among delivery and cargo vans. The market for both e-commerce and on-demand delivery services, such as grocery and restaurant deliveries, has increased dramatically over the past decade and surged during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to research by Capital One, Amazon alone processed nearly 675,000 packages each hour nationally in 2023, many of which were same- or next-day deliveries. Nationwide, the number of same-day e-commerce deliveries among all retailers is anticipated to grow from around 230 million in 2018 to over 5.8 billion in 2026 – a near 26-fold increase.

Even at de minimis rates, clean delivery fees could raise hundreds of millions of dollars annually in California for freight electrification projects and programs. For example, Colorado’s retail delivery fee, which is set at a flat rate of $0.28 and exempts businesses with annual sales under $500,000, raised nearly $76 million during its first year of implementation, according to analysis by the Council of State Governments. While this is certainly a significant chunk of change, the amount raised in Colorado amounts to a mere half of one percent of the annual revenue from online sales in the state. Given that online retailers’ annual revenue in California is nearly seven times larger than in Colorado, funding for electrification from a similarly structured delivery fee program could be significantly greater.

Although a crude estimate, applying Colorado’s stats to California suggests the state could be looking at over $460 million in annual revenue from a delivery fee program – nearly three times the amount appropriated for HVIP in Fiscal Year 25-26.

Give clean trucks a (tax) break

One straightforward method to reduce incremental costs between zero-emission and fossil-fueled trucks is through the implementation of tax breaks or holidays for clean trucks. Sales and use taxes for vehicle purchases differ widely among states, but most levy taxes between five and eight percent for new vehicle purchases. Exempting zero-emission MHDVs from all or a portion of sales and use taxes could provide a valuable incentive for clean trucks. For example, a battery-electric tractor truck with an upfront price of $400,000 could pay $30,000 in state taxes alone (not to mention Federal Excise and local taxes). By exempting purchasers from a portion of state taxes, fleets could be able to take advantage of the significant operational savings offered by battery-electric trucks much sooner.

Doubling down on deploying charging infrastructure

Expanding nationwide access to affordable zero-emission charging infrastructure is a key companion to vehicle price reductions in the transition toward cleaner on-road freight. A 2024 report by the California Energy Commission estimates that the state will need just under 115,000 charging ports for battery-electric MHDVs at depots and en route locations before the end of the decade. Today, the state has over 16,000 currently in operation or under development. Although California and other states have made some progress in zero-emission MHDV infrastructure deployments, accelerating these efforts nationwide is foundational to transitioning to a clean on-road freight system.

While the fee mechanisms discussed above are well-suited to contribute to new and existing infrastructure incentives and investments, policymakers would be wise to also invest in comprehensive, multi-agency infrastructure strategic planning in close collaboration with industry, utilities, communities, and academics. Funding strategic planning efforts, along with related software tools to identify suitable station locations and designs, could help to accelerate timelines for station construction.

Keeping up the pace

While federal rollbacks and hurdles may certainly slow progress, California and other leading states can help to pick up the slack and maintain the needed momentum. By doubling-down on strategic policies, targeted investments, and problem-oriented solutions, states can pick up the slack and help deliver a cleaner, globally competitive, more cost-effective, energy-efficient, and equitable goods on-road freight system.