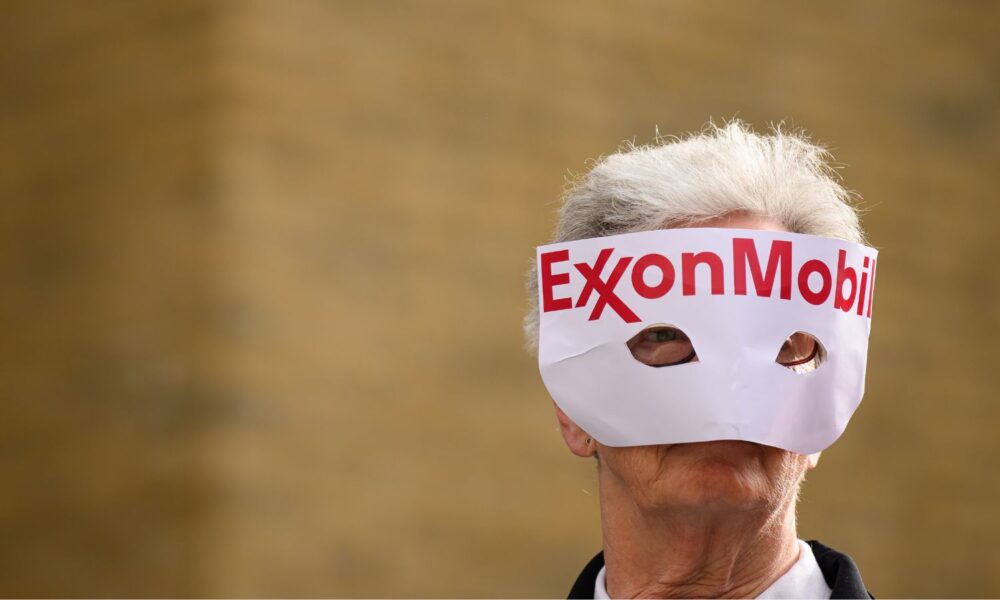

Most fossil fuel companies are happy to let their trade associations take the lead on fighting accountability measures in court. ExxonMobil, however, has repeatedly used its status as the world’s largest publicly-traded oil and gas company to act like a schoolyard bully, flexing its muscles on the global playground. The company’s new lawsuit against California’s agenda-setting climate disclosure laws underscores what decades of investigation and litigation have shown: ExxonMobil will go to nearly any length to avoid accountability for its role in the climate crisis.

ExxonMobil’s challenge to California’s disclosure laws carries implications far beyond one company or one state. California is the world’s fourth-largest economy, and these laws could set a precedent for national climate disclosure standards—particularly as the US Securities and Exchange Commission climate rules and other federal disclosure requirements have been significantly weakened and face uncertainty.

It’s not the first time ExxonMobil has gone after watchdogs in court: the company filed a precedent-setting lawsuit against its own shareholders just last year. This dual assault on state law and shareholders shows that the company would rather spend millions on lawyers than report verified emissions data or respond genuinely to shareholder concerns.

What California’s laws actually require

ExxonMobil’s lawsuit targets two bills: SB 261, known as the Climate-related Financial Risk Act, and SB 253, the Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act. SB 261 requires companies with over $500 million in revenue doing business in California to biennially disclose climate-related financial risks such as damage to buildings or decrease in consumer demand. SB 253 requires companies with over $1 billion in annual revenue doing business in California to report annually on carbon emissions produced from their operations, purchased energy, and use of their products.

The last category of emissions, known in carbon accounting as Scope 3 emissions, is an ongoing source of friction between regulators and oil companies. The latter claims they should not be held responsible for emissions produced by the burning of products like gasoline even though Scope 3 represents around 90 percent of fossil fuel companies’ total emissions. ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods has admitted that the real issue is the cost of abating emissions, which he believes should be passed on to consumers.

Like the SEC regulation on climate-related disclosures (rolled back weeks after Trump took office last January), California lawmakers introduced the bills after years of voluntary corporate climate disclosure proved inadequate. ExxonMobil thinks the laws’ actual purpose is to persecute fossil fuel companies, conveniently ignoring the fact that large fossil fuel and cement companies are responsible for the vast majority of the emissions that science shows are driving changes in the earth’s climate.

Hiding behind a bogus “free-speech” shield

The laws treat disclosure of information like emissions as “commercial speech,” akin to a food company disclosing ingredients or allergens, or a pharma company listing side effects. ExxonMobil’s lawsuit argues that any information related to climate change is actually “political speech,” which enjoys more protection under the First Amendment. By that logic, any corporate disclosure requirement—from nutrition labels to toxic release inventories—could be challenged. It’s a dangerous argument that draws on the Supreme Court’s expansive interpretation of corporate free speech in Citizens United v. FEC, an approach that, if extended here, could undermine disclosure regimes across sectors.

Various corporations have wielded similar arguments to stop regulations with little success. In fact, a 2024 lawsuit filed against the California laws by the US Chamber of Commerce recently failed to obtain a preliminary injunction because the court found SB 253’s emissions requirements were “uncontroversial” and that SB 261’s disclosures were “reasonably related” to informing investors and the state’s substantial interest in addressing climate risks.

So why does ExxonMobil continue to flog a dead horse? Because it wants to intimidate other states considering similar disclosure laws, just as it used the law to twist the arms of shareholders that had the temerity to demand transparency into the company’s climate impacts.

Squelching shareholder oversight

ExxonMobil put shareholders in its sights after a high-profile win by investors in 2021 that resulted in the installation of three members of a climate-minded hedge fund on the company’s board of directors. The change did not produce greater appetite for emissions disclosure, however.

In January 2024, ExxonMobil filed a lawsuit in Texas against shareholders Arjuna Capital and Follow This to block a resolution the groups submitted asking the company to reduce the full spectrum of its carbon emissions. The case marked the first time a major corporation sued investors over a climate-related resolution, bypassing the SEC’s established process for adjudicating such disputes. Exxon pushed ahead with the lawsuit even after the shareholders dropped the resolution. The lawsuit created such a chilling effect that no climate-related resolutions appeared on ExxonMobil’s 2025 proxy ballot for the first time in at least a decade.

Just weeks before filing its California lawsuit, ExxonMobil introduced another controversial mechanism to suppress shareholder voice: a “retail voting program” that allows individual investors to automatically vote their shares in line with board recommendations at annual shareholder meetings (individual, or “retail,” investors own about 40 percent of the company’s shares). While ExxonMobil’s program only offers one option—to back the board—services like As You Sow give investors voting choices across a range of positions. Another crucial distinction is that organizations defending shareholder rights do not have a financial interest in the outcome of their recommendations.

The SEC gave its speedy approval to the power grab, unsurprising to anyone who has followed the agency’s recent trajectory. Under Trump’s SEC Chairman Paul Atkins, the supposedly “independent” agency is stripping away investor power and handing it to corporate leaders. And in a naked display of disdain for financial regulation, Atkins opined in an October speech that companies registered in Delaware—as many fossil fuel companies are—could use state law to reject shareholder resolutions across the board. So much for shareholder-based capitalism.

Shareholder oversight has also been in the political crosshairs on Capitol Hill. In September, the Republican leadership of the House Financial Services Committee held a hearing on SEC rule 14a-8, which provides guidance on whether or not a company must include a shareholder’s proposal in its proxy statement. The hearing’s stated purpose was to assess whether the shareholder proposal process “has been co-opted by activist investors.” The hearing—a continuation of Republicans’ anti-ESG crusade—provided a launch pad for several bills structured to discourage shareholder proposals and further tilt the playing field in favor of corporate boards and executives.

Opposing transparency

ExxonMobil’s lawsuit discounts the fundamental intent of the California laws: to equip investors with the information they demand about how companies are planning for a future changed by global warming. Investors overwhelmingly supported the SEC climate disclosure rule because they need such information to assess risks to companies’ business models. That rule provoked similarly vicious pushback from the fossil fuel industry, becoming the target of lawsuits by the American Petroleum Institute and several attorneys general from oil-rich states.

ExxonMobil’s resistance to climate disclosure continues a well-documented pattern. Though the company’s own scientists warned management about climate change decades ago, the company opted to deny the science in order to continue profiting from its polluting business model. ExxonMobil has continued to block any policy that would mandate and standardize corporate transparency around heat-trapping emissions and climate actions.

California’s laws will remain in effect during litigation, and companies covered by them still face a deadline of January 1, 2026. Meanwhile, shareholders, state regulators, and affected communities continue pressing for climate accountability. ExxonMobil should drop the fake free speech shield and engage in a fair fight with full transparency.