For many reasons, California’s agricultural regions are in a state of flux. A fundamental land use transition is underway, motivated in part by the passage of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act more than a decade ago and market forces, such as changing crop prices and tariffs, which are currently hitting the agricultural sector hard. What we know is that the future will not look like the past. And that could be a good thing.

For much of the 20th century, if not earlier in some instances, a pattern of large-scale farm consolidation continually privatized the profits and socialized the harms. Large landowners, like financial investors, multi-billion-dollar farming companies, and individuals like the wonderfully infamous Stewart Resnick benefit from the status quo. And just to be clear, the status quo is that in the fourth largest economy in the world, we have some of the poorest and most polluted communities barely making it.

Land use transitions do not happen passively; they are choreographed by powerful actors and profoundly shape rural economies and community opportunities. Today, California’s Central Valley is dominated by an extractive economic paradigm. But what if the future could be different? What if the economy could benefit more people? What if the Central Valley could be a healthy place to live and work? These are the central questions guiding UCS research on cropland repurposing.

Today, UCS released a road map to accelerate a just land transition in California’s Central Valley. One of the most immediate ways to ensure the ongoing land transition is led by communities is to ensure that projects contributing to land use transitions actually provide meaningful benefits to communities.

A just land transition defines “Meaningful Benefits” for communities

California’s Department of Conservation (DOC) has a head start in this area. In April, DOC adopted revised guidelines for its Multibenefit Land Repurposing Program (MLRP), which included a robust definition of “meaningful benefits.” The MLRP program is investing $90 million in projects that repurpose irrigated agricultural land and address unsustainable groundwater usage while “providing community health, economic wellbeing, water supply, habitat, and climate benefits”.

In November, California voters approved an historic Climate Bond—Proposition 4. $10 billion will be invested through the bond to support climate resiliency programs across the state, including to improve sustainable water management and advance cropland repurposing projects. Proposition 4 requires that at least 40% of the overall investment, $4 billion, fund projects that provide direct and meaningful benefits to vulnerable and disadvantaged communities.

Funding from Proposition 4 could be appropriated as early as this summer. It will be up to the state to ensure that projects receiving public funding succeed in advancing the program goals, including upholding its commitment to vulnerable and disadvantaged communities. A key component of effectively evaluating projects lies in defining whether a project provides “meaningful and direct benefits.” Unfortunately, the legislature did not settle on a uniform definition when it passed the bond last year.

If adopted by the legislature, the Department of Conservation’s definition of meaningful benefits can provide guidance to all implementing agencies and consistent guardrails to ensure this major investment of public funding yields the public benefits that were promised to California residents – and in particular to marginalized and disadvantaged communities.

A just land transition is guided by clear values

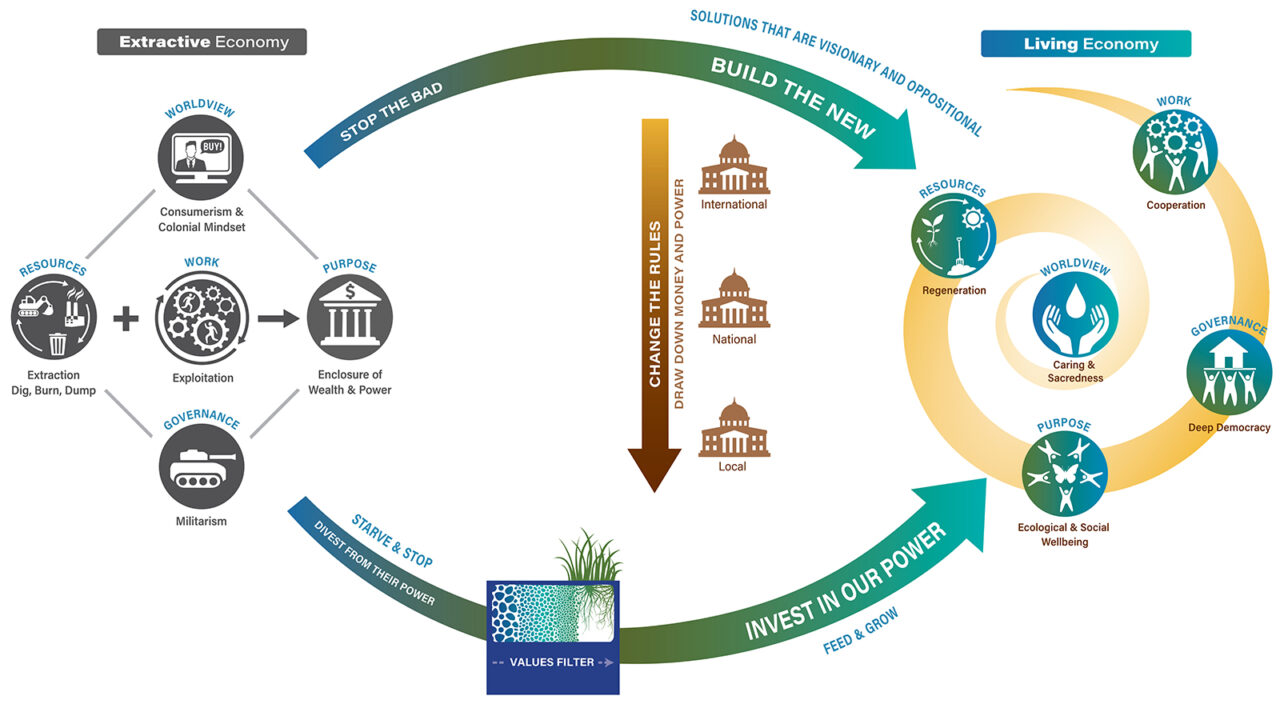

UCS put together this road map toward a just land transition in partnership with allies and guided by a set of core values. Following these north star principles, the policy brief provides a set of short and long-term steps to facilitate and accelerate a justice-oriented land transition. As in the visualized just transition framework here from the Climate Justice Alliance and Movement Generation, a just land transition shifts us from an extractive economy to a living economy.

It is important to be explicit about values and to test policy solutions against those values, otherwise one extractive economy may just be replaced by another. For example, in one of her seminal works, Golden Gulag, Professor Ruth Wilson Gilmore outlined how drought, debt and development dynamics led to irrigated cropland being replaced by the prison-industrial complex throughout the 1980s and 1990s. She explained how new prisons “light the night sky along the Central Valley’s ‘prison alley’…the result of the confluence of political and economic forces embedded in, and built on, the historical power of agriculture and resource extraction in the state” (Gilmore 2007). Indeed, 18 of the 24 new prisons sited between 1982-1998 were on formerly irrigated cropland.

Throughout various land use transitions in California, the state government has been a complicit partner in enriching certain groups to the detriment of others. Between racist laws and genocidal acts of 1800s to the purchasing of land at inflated value from farmers, with public funds, for use by the California Department of Corrections in the late 20th century—it goes without saying that our elected representatives have moments where their decisions affect constituents differently AND how voters shape government priorities also matter. The 1980s prison expansion may not have been possible without the $495 million New Prison Construction Bond Act of 1981 ($1.7 billion in 2025, adjusted for inflation).

We can do better.

A just transition empowers the people to drive the change

A just land transition requires that people who are impacted have a seat at the table. As I alluded to at the start of this blog, there are already a lot of tables and seats for certain types of farmers and landowners. Yet frontline communities, or those communities located in proximity to cropland transition, are likely to experience the first and worst impacts and are often structurally excluded. There are ways to build power and empower folks so they can drive the change:

- Require a process for ensuring affirmative community support for land transition projects involving public funds. Such processes could include an allowance for a right of first refusal by frontline communities or a meaningful process of engagement with the frontline community(ies) for any proposed community benefits agreement.

- Develop local civic infrastructure that will support a just land transition by building decisionmaking power in frontline communities. Examples include community land trusts to acquire and manage land, community choice aggregators for local renewable energy, and cooperatives or other models that center community participation and ownership.

- Fund organizations to develop networks of local elected officials and community leaders who want to be innovators and champions of just land transition. These members could be, for example, mayors, council members, and county supervisors. (See for example, Community Water Center’s Community Water Leaders Network and the AGUA Coalition [La Asociación de Gente Unida por el Agua/Association of People United for Water])

- Expand direct investment in community-based organizations and technical assistance providers working on just land transition. Direct investment will continue building local capacity for project development, implementation (including long-term maintenance), and policy advocacy, as well as evidence for scaling place-based solutions for the region.

A just land transition that is based on intentional and strategic cropland repurposing could help shift the status quo from an unsustainable and extractive agricultural system to a just and living economy, at a feasible pace. To do so means adopting and following guiding principles—these above steps and many more accelerate a just land transition in California’s Central Valley. Everyone has a role to play, which is why our roadmap suggests steps specifically for the legislature, regulatory agencies, local governments and the philanthropic sector.