While the date will go unnoticed by most, January 14, 2026, marks a milestone in world history. As of today, the world has gone eight years, four months, and 11 days without a nuclear test—the longest period since the Trinity test without a nuclear explosion. From now on, every day without a nuclear explosion will set a new record. But this winning streak is being threatened by ill-informed and misleading remarks from the Trump administration, which recently argued for the United States to resume nuclear testing.

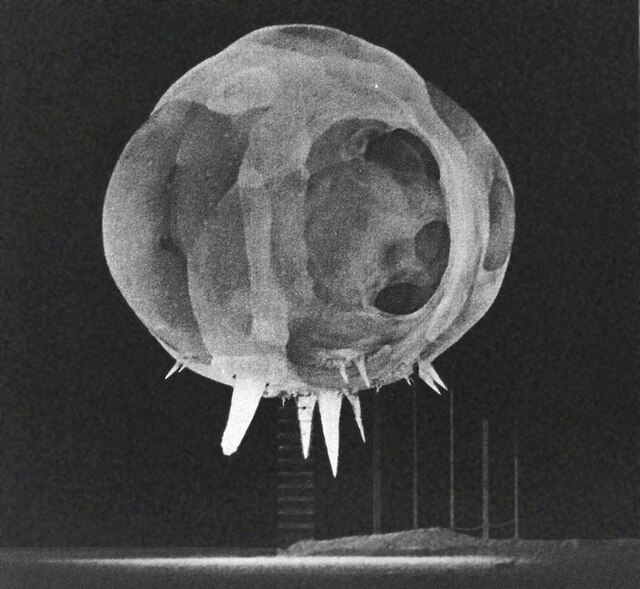

Since 1945, at least eight countries have detonated more than 2,000 nuclear weapons as part of national testing programs. The most recent nuclear test was conducted by North Korea on September 3, 2017. All other nuclear armed states conducted their last nuclear tests between 1990 and 1998. Although there was a temporary pause in testing between 1958 and 1961 as the United States and Russia attempted to negotiate an early moratorium, it resumed with alacrity thereafter.

The Trump administration’s recent call to resume nuclear testing “on an equal basis” with other nations is now threatening this fragile moratorium. It is all the more surprising given that the United States has perhaps the most to lose from any resumption of full-scale testing. It is important, therefore, to understand what has permitted and sustained this latest cessation in nuclear explosive testing and what it shows about the capabilities and ambitions of the nuclear states today. Any decision to test may be driven by either technical or political factors (or both), however, it is clear that doing so today would be dangerous and unnecessary regardless of motivation.

The nuclear taboo

In the 21st century, nuclear explosive testing has entered the realm of taboo. North Korea is the only nation to have tested this century and has been labeled a rogue state as a result. In the eyes of most of the world, such testing is seen as an emerging threat and as a source of tremendous regional instability.

In 1996, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) opened for signatures and has since been signed by 187 nations and ratified by 178—an overwhelming global majority. The treaty bans all forms of supercritical nuclear testing. Although the United States has signed (but never ratified) the treaty, its participation comes with the responsibility to uphold its conditions or else oppose the 92% of global states that do.

For western alliances intent on restraining the nascent nuclear ambitions of potential adversaries, it has been well understood that upholding the conditions of the CTBT is effective leverage for limiting nuclear proliferation elsewhere, including the development of more sophisticated arsenals by countries with limited or no test experience. The post-Cold War nonproliferation agenda has, indeed, relied heavily on testing being taboo and something done only by “bad actors” intent on ignoring the global norm. An advanced nuclear state that willingly breaks this taboo would abandon its existing technical advantage and future diplomatic leverage against developing or aspiring actors, and would shatter yet another pillar of international cooperation.

Advancing scientific capabilities

The fact that more advanced nuclear nations have been content to suspend their test programs for more than 30 years is not only for the sake of diplomatic leverage but also because of advancing technical capabilities. The technical need for full-scale explosive tests is simply no longer what it used to be. Non-nuclear scientific experiments and laboratory capabilities, coupled with ever-advancing computation, have largely obviated the need to conduct full-scale explosive testing.

Using such capabilities, the United States already tests “on an equal basis” with its nuclear peers, despite the administration’s suggestion to the contrary. Today, nuclear weapons components are extensively tested, both individually and integrally, right up to the edge of nuclear criticality (using subcritical tests that allow scientists to characterize the reliability and implosive dynamics of plutonium combined with the high explosives used in the weapons themselves).

Advanced nuclear states are technically well beyond the point of exploring whether their weapons will detonate reliably and, instead, are focused on the potential for small deviations from the weapon’s originally designed yield. Resolving such questions does not require full-scale testing but rather a sophisticated understanding of aging, how materials behave close to nuclear criticality, and highly instrumented diagnoses of those processes, all of which are more difficult or impossible to glean from the type of tests conducted in the atmosphere and underground throughout the Cold War. The United States possesses or is developing some of the most sophisticated tools to do this, including new infrastructure for subcritical tests that allows more detailed and refined characterization of explosively driven plutonium than can be done in a one-off, explosive demonstration of a particular warhead design.

Proponents of resumed testing have pointed to controversial US State Department accusations that Russia and China may have conducted very small-scale nuclear tests that could have evaded international detection. So called “hydronuclear” or “low-yield” tests may present some benefit for less-sophisticated nuclear states that lack advanced tools to diagnose the nuclear physics involved in subcritical tests. China, Russia, and the United States all possess such capabilities and all three conduct subcritical tests (which are allowed by international agreement). The relative benefits of tests that barely exceed nuclear criticality is therefore significantly diminished.

If nuclear deterrence requires projecting confidence in a nation’s nuclear arsenal, a return to testing by the United States would be construed as an embarrassing admission that the most advanced stockpile stewardship initiative in the world (and that the United States has relied on for decades) is somehow insufficient to allow a binary understanding of whether our weapons will work or not. While the Trump administration may view a test as a contribution to deterrence, it may actually have the opposite effect by projecting an irreconcilable lack of confidence in the US stockpile.

Indeed, it is noteworthy that calls for resumed nuclear testing in the United States on the basis of concerns about reliability are not emanating from the scientists, engineers, and experts charged with designing and maintaining the nuclear arsenal. These experts repeatedly and emphatically state their confidence in the tools they have at hand and with their annual certification of the stockpile based on those tools. Rather, such calls come from think tanks and advisors aligned with the administration who favor demonstrations of force and who lack a deep technical understanding of US scientific capabilities that are now extremely mature. Advocacy for renewed testing is politically driven—not technologically driven.

Public opposition and acknowledgment of risk

In addition to the international norms (which are nearly universally accepted under the CTBT) and the lack of technical motivation, the moratorium on nuclear testing is further reinforced by staunch public opposition.

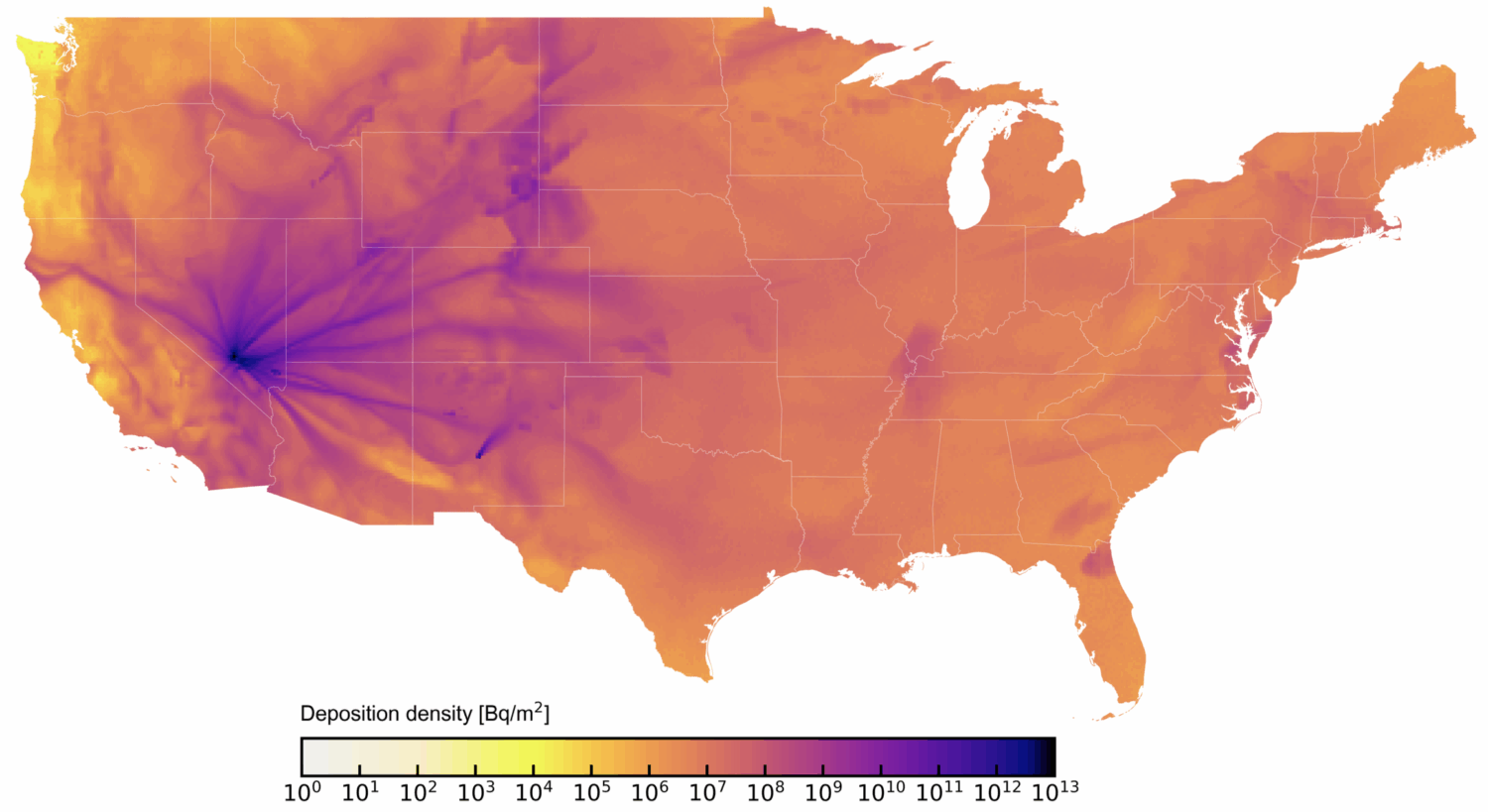

In addition to the 928 tests conducted just outside Las Vegas, Nevada, the United States conducted 105 nuclear tests in the Pacific, and at least 10 others in Alaska, Colorado, Mississippi, and New Mexico, including efforts to employ nuclear weapons for industrial purposes. As the human and environmental consequences from these tests became better understood, public opposition mounted. Aboveground tests spread fallout to downwind communities, resulting in generational health impacts and the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty. Underground tests are acknowledged to have left behind an astounding 300 million curies of radiation at the Nevada Test Site, leading to the contamination of some 1.6 trillion gallons of water in the local aquifer. Harmful radioisotopes from nuclear detonations have lifetimes measured in millennia, which has led previously affected communities to strongly oppose any return of testing to their backyards.

In 2025, the Nevada state legislature unanimously passed a resolution opposing any resumption of nuclear testing in the state, symbolizing the resolve of residents and their government to avoid further harm to their state and their resources. The administration’s recent suggestion that such testing should resume has other communities rightfully on alert.

Keeping the peace

While the world has quietly broken a record for the longest period of time without a nuclear test, it is clear that this stability is fragile. The cessation of nuclear testing by all but one nation has been sustained through a recognition of mutual benefit by China, Russia, and the United States, and the shared understanding that unrestrained tests lead to competition, instability, and a degree of uncertainty that can scarcely be afforded on top of our existing global precarity. Reopening this Pandora’s box is both unnecessary and unwise.

If you would like to help strengthen the current moratorium on nuclear testing, join us in our efforts by supporting the RESTRAIN Act (HB 5894 and SB 3090), which would officially prohibit nuclear explosive testing in the United States.