Over the last year, two California oil refineries, Phillips 66 in Los Angeles and Valero in Benicia, have announced their plans to shut down. These unexpected closures add urgency to the process of planning for an orderly transition from gasoline to renewable electricity as California’s primary transportation fuel. This week, the California Energy Commission announced its recommendations to avoid a gasoline supply crisis in California. Oil industry astroturf groups have been quick to blame California’s regulatory environment for the refinery closures and suggest that reversing course could solve the problem. But this is more political opportunism than productive problem solving. Reversing California’s air quality and climate regulations would not address the immediate challenges and would compromise the health and welfare of California’s people. California needs to increase flexibility and restore competition to its gasoline market to protect consumers and ensure reliable supply. But that can and must be done without compromising climate and public health.

My colleagues and I have been tracking the progress of California’s petroleum phaseout for the last several years and have a science-based proposal to make California’s gasoline market more flexible and competitive while advancing clean air and climate mitigation in California. We evaluated a program discussed last year in the California Energy Commission’s Transportation Fuels Assessment, to allow the voluntary use of conventional US gasoline in place of gasoline that meets California’s more stringent regulations. Fuel sellers who take advantage of this flexibility would contribute to a mitigation fund that would be used to help drivers of older more polluting cars upgrade to an electric vehicle (EV).

This flexibility program is voluntary, and contributions to the mitigation fund would only be made when doing so is less expensive than acquiring California-specific gasoline. It would make California gasoline markets more competitive, which will save drivers money, particularly by avoiding price spikes when acute shortages arise due to refinery closures. And because older cars are responsible for a disproportionate share of pollution, our analysis (discussed below) finds that the benefit of replacing older cars with EVs would outweigh the extra pollution from conventional gasoline, leaving the state with cleaner air. This new analysis builds on an earlier analysis conducted with the Greenlining Institute that found that a well-designed program to replace California’s oldest and dirtiest cars will save money and lives and focus these benefits in the communities where more of these older cars are operating, which are disproportionately Latino and Black Californians and lower-income households.

In the next few years, California should modernize its gasoline regulations to reflect changes in vehicle emissions technology and the latest science, which can make the gasoline market more flexible and competitive while protecting air quality and public health. This could be done in coordination with other Western states, to create a harmonized market. But to do the regulatory overhaul properly will take time. In the meantime, our proposal would increase flexibility, which will be especially important in the next few years as the California gasoline market adjusts to the closure of two large refineries.

Gasoline regulations are only one of the barriers to California developing a flexible and competitive gasoline market, which include the lack of physical infrastructure to move fuel between markets, federal shipping regulations (The Jones Act), and the geography of the United States. Our proposal is just one piece of a much larger puzzle, which will require oversight of the petroleum market by regulators and the construction or repurposing of physical infrastructure to serve the changing needs of the California market.

Managing the transition from California’s history as a major oil and car state to its future as a leader in clean transportation is a complicated job that will play out over coming years. The world is watching, and with smart policies, California can manage the phaseout of petroleum while protecting the health and welfare of its people.

A petroleum phaseout plan is underway—and off to a rocky start

California is in the midst of a petroleum phaseout that will leave the state healthier, wealthier and generally better off. But for all these opportunities, the transition also poses serious challenges, starting with a gasoline market that is suffering from concentrated market power. The gasoline market concentration in California is the result of business decisions by oil companies that may benefit their shareholders, but harm consumers, refinery workers and refinery communities. In light of these changes, some California regulations, adopted when the gasoline market was more competitive, are no longer working as designed.

California was once a self-sufficient “fuel island,” with a large number of companies extracting oil, refining it and selling gasoline in competitive market. Today, a shrinking number of companies refine and sell gasoline in the state, which is increasingly reliant on gasoline imports. California regulations need to adapt to changing circumstances, reflecting the state’s shift from a fuel island to a more connected market.

While the timing of the refinery closures announcements was unexpected, it is no surprise that California’s fuel market is in transition. UCS and other groups have been calling for the state to develop a petroleum phaseout plan since 2022, and the government has responded, created new regulatory authorities and a planning process at the California Energy Commission (CEC) and other state agencies. Two key elements of the planning process are the Transportation Fuels Assessment, published by the CEC in August of 2024, and the Transportation Fuels Transition Plan, which is in progress under the leadership of the California Air Resources Board (CARB).

This deliberate planning process, including a work group I served on, has been upended by the refinery closure announcements. Prior to the announcements, most people assumed that gradually declining demand for gasoline was the key driver of a transition that would play out over the next two decades. But the unexpected refinery closures mean that rapidly declining supply of gasoline refined in California is creating a potential gasoline supply crisis that the state must address over the next few months. Since the most recent refinery closure announcement in April, the CEC has been gathering input from stakeholders and conducting analysis to develop recommendations, which it released in late June. These recommendations will inform the response by the state agencies and the legislature in the coming weeks and months.

An increasingly uncompetitive gasoline market

While the press focuses on the announcements of refinery closures in the last year, the number of oil refineries operating in California has been falling steadily since the 1980s. The industry has been steadily consolidating from 40 California refineries in 1983 to 13 in 2025[i]. This reduction in the number of refineries was driven primarily by consolidation into larger refineries, in a process that is occurring not only in California but across the US and around the world. The average throughput of California’s refineries doubled in this period as the total production capacity fell just 30 percent.

In the last few years, this consolidation in California has created an increasingly severe problem with concentrated market power, with a smaller number of companies controlling the market, especially the gasoline market. In 2024, the CEC noted that just 5 companies controlled 98 percent of the gasoline refining capacity, which was already raising red flags. But by the time Valero closes the Benicia refinery in 2026, just three companies will control more than 90 percent of California’s gasoline refining capacity. When markets are this concentrated, competition between private companies is no longer adequate to ensure that consumers get fair prices[ii].

California is no longer a self-sufficient fuel island

California is often described as a fuel island. The CEC Transportation Fuel Assessment explains this as follows:

California is essentially a fuel island. There are no pipeline inflows of refined fuel into the state, and cargo ships delivering CARBOB take three to six weeks to arrive from distant facilities capable of producing CARBOB. By contrast, many other states have a broad network of pipeline flows, multiple regular sources of marine imports, and similar fuel specifications to neighboring states, all of which help to maintain supply resiliency and hence price stability in the market.

Historically, trade accounted for a small share of California’s gasoline supply, mostly coming in to address episodic short-term shortfalls or surpluses. The time lag associated with securing imported gasoline that met California’s unique requirements (called CARBOB) contributed to gasoline price volatility, and addressing this volatility was a major focus of the Transportation Fuels Assessment. However, in light of the two refinery closure announcements, imports are no longer an occasional strategy to deal with short term issues, but an important part of the California fuel landscape, expected to supply 15 percent or more of the state’s gasoline going forward. In addition to gasoline imports, California also exports fuel to Arizona and Nevada and exports a lot of diesel to global markets.

The implication is that California is no longer a self-sufficient fuel island, and will rely on imports to supply a persistent and significant share of its gasoline into the future. This is a major change in California fuel marketplace, and it has important implications for ports, ships, pipelines and gasoline regulations. While our analysis and recommendations focus on gasoline regulations, changes will be needed in other areas as well, including consideration of adjustments to other policies and regulations and repurposing physical infrastructure[iii]. Many of these topics are discussed in the Transportation Fuels Assessment and the recent recommendations from the CEC.

CA gasoline regulations are ready for an update

California’s gasoline regulations were an important part of the state’s strategies to address air pollution caused by gasoline-powered cars. When these regulations were adopted in the 1990s and early 2000s, they provided rapid and significant improvements in air quality and public health, which more than justified the added costs associated with producing this special fuel. However, much has changed in the two decades since these regulations were last significantly revised.

Modern cars are much less sensitive to small changes in fuel characteristics than older cars, and over time gasoline regulations for the United States have gotten much closer to California’s. This means the air quality benefits of California’s unique fuel regulations are much smaller than they once were, and most of the benefits of the more stringent fuel regulations come from the oldest cars on the road, which account for smaller share of total miles driven in California each year.

Meanwhile, the costs of California’s unique fuel regulations are rising, especially the role the regulations play in keeping other companies from selling gasoline in California, making the California market less competitive. In a flexible and competitive market, higher gas prices in California should lead gasoline producers elsewhere to ship fuel there. But this normal market response is stymied in California by a combination of physical and regulatory barriers and the concentrated market power in California’s gasoline market. Its unique gasoline regulations make it more expensive and time-consuming to import gasoline and prevents the state from using non-California gasoline produced in California refineries.

What if California allowed the use of conventional US gasoline?

In the 2024 Transportation Fuels Assessment, CEC proposed a strategy it called a Non-CARBOB Fee Allowance, which would allow the limited use of gasoline that did not meet California’s unique requirements when supply was tight in exchange for a contribution to a mitigation fund used for air quality improvement strategies in non-attainment regions or other EJ communities. CEC noted that the air pollution impacts of this proposal were not well understood, so UCS stepped up to fill the void.

Based on earlier analysis my colleagues did with The Greenlining Institute, Cleaner Cars, Cleaner Air, we know that replacing the oldest cars has major benefits, reducing pollution, saving lives, and saving people money while addressing harms that fall disproportionately on Latino and Black Californians and lower-income households. Based on this work, UCS developed the hypothesis that replacing older cars might effectively mitigate the extra pollution from using non-California gasoline.

To evaluate this hypothesis UCS conducted analysis using the EPA MOVES model to evaluate a program that would allow flexibility to use conventional US gasoline in California. Fuel sellers that chose to take advantage of this flexibility would contribute 25 cent per gallon to a mitigation fund used to replace older cars similar to Clean Cars for All. We found that if 10 percent of the gasoline in California in 2030 was replaced with average US gasoline, it would increase particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions by less than 1 percent[iv]. But this pollution could be mitigated by replacing 50,000 pre-2004 cars with EVs, which would reduce PM2.5 emissions by slightly more than the increase associated with the fuel change. We also evaluated volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), in which case the increased emissions from the fuel change were smaller and the benefits of replacing older cars were larger.

| NOx | VOCs | PM2.5 | |

| Change from replacing 10 percent of California gasoline with average US gasoline | +0.47% | +0.15% | +0.85% |

| Change from replacing 50,000 pre 2004 vehicles | -2.46% | -2.1% | -0.99% |

To put the 25 cent per gallon mitigation fund in context, if California consumes 10+ billion gallons of gasoline in 2030, of which 1 billion gallons is replaced with US average gasoline, the fund would have $250 million, which should be sufficient to support the replacement of approximately 25,000 older cars each year. Within two years, the state would have lower PM2.5 pollution through the vehicle replacement program, and the reductions in NOx and VOCs would be even faster. Moreover, the people who replaced their older cars with EVs will no longer be buying gasoline, moving the state forward in its petroleum phaseout process.

Replacing the oldest, dirtiest cars with EVs is a win-win

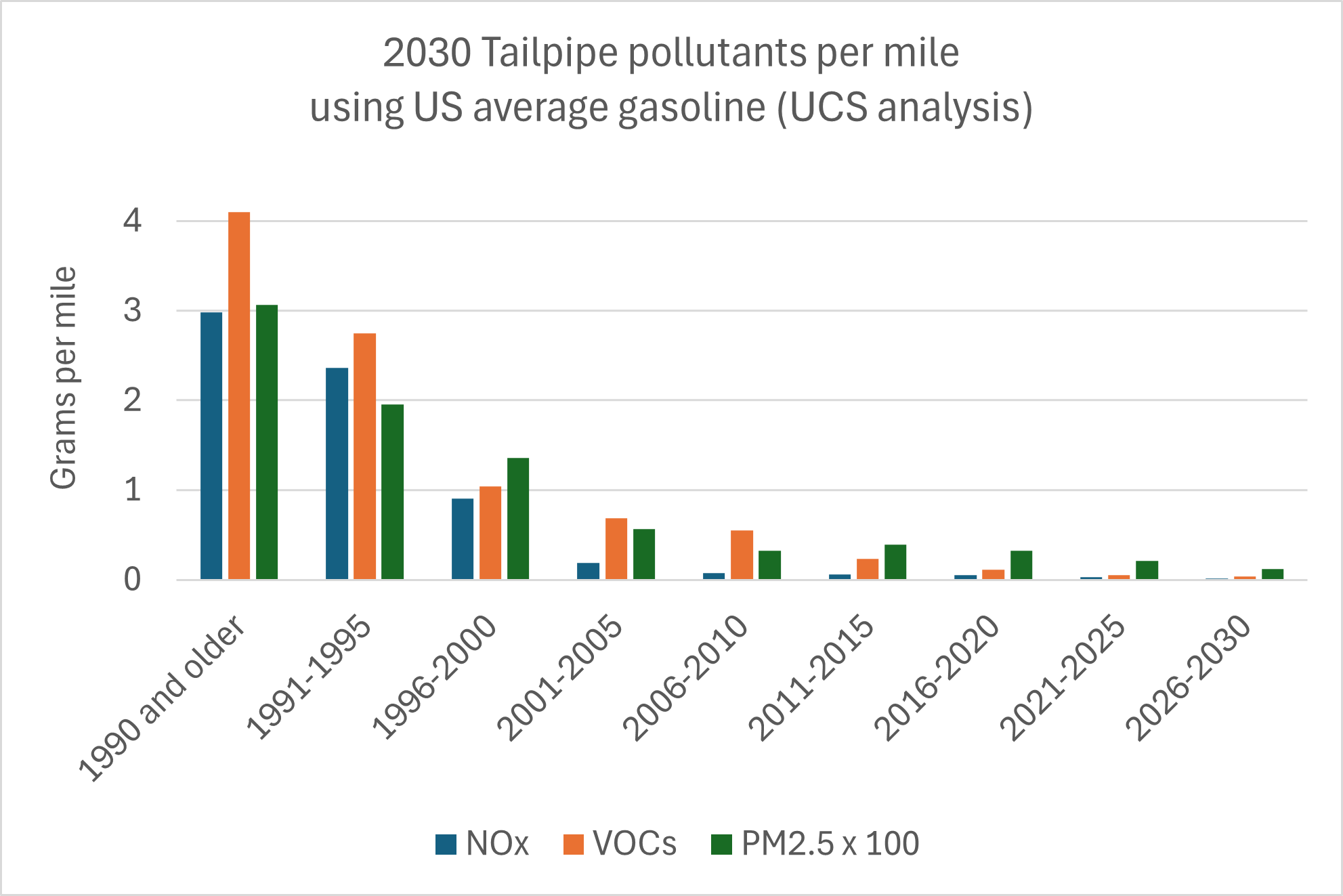

To understand why vehicle replacements policies are so valuable, the following graph shows the modeled emissions per mile of pollutants from light duty passenger vehicles of different ages. These results evaluated 2030, but we also considered other years with qualitatively similar results.

Pollution from older cars is much higher than newer vehicles on a per-mile basis. This explains why getting these older cars off the road is an effective way to address incremental pollution from relaxing fuel regulations. While pollution per mile is much higher for older vehicles, total pollution from more recent cars is still significant, since newer cars account for a larger share of total miles traveled.

Our analysis backs up our proposal, but more work is needed to develop a program

Our preliminary analysis strongly supports our hypothesis that a program allowing flexibility in gasoline markets could effectively mitigate associated pollution by supporting the retirement of older cars. We have more work to do to finalize our analysis and will add a link to the full report to this page when it is complete. But given the quickly evolving discussion of how to address a potential California gasoline crisis, we thought it was important to share our initial results now. The design and implementation of a program will require more work to ensure that it works effectively and equitably.

We evaluated a voluntary program with a mitigation contribution of 25 cents per gallon. This is a starting point that would benefit from more detailed analysis, some of which is beyond the scope of our current study. A different contribution level or a more complex structure based on fuel properties could be more effective at meeting the goals of improving the flexibility and competition in California’s gasoline market while generating funds to mitigate air pollution. Likewise, while we studied the replacement of light duty passenger cars, increased fuel imports may increase pollution exposure at communities near fuel import terminals. Targeting a portion of mitigation funds to address these impacts, potentially by replacing old polluting diesel trucks operating there, would also be appropriate mitigation. Changes to gasoline vapor pressure regulations are another strategy that could make California’s gasoline supply more flexible, and in that context targeting replacement of smaller off-road road engines could be a well targeted mitigation strategy.

Beyond deciding on mitigation contribution levels and the focus for mitigation, the design of vehicle replacement programs is also important. A study my colleagues conducted together with Greenlining in 2023 proposed the following improvements to vehicle retirement programs to maximize their health and equity benefits.

- Prioritize existing incentive programs, such as Clean Cars 4 All and the Clean Vehicle Assistance Program, toward priority populations owning old cars.

- Target outreach and education to households in areas with high concentrations of old cars and limited uptake of zero-emissions vehicles.

- Provide transportation solutions that go beyond private passenger vehicles.

- Evaluate and adjust incentive programs based on changing conditions in the electric vehicle market.

In conclusion

Bailing out the oil industry—with public dollars or our public health—isn’t the answer to gasoline affordability. The answer is to accelerate our transition away from petroleum, while bringing more flexibility and competition into our gasoline market to keep prices affordable during the transition. California can build a bridge from its fuel island to other markets- by allowing more gasoline into California when supplies are tight, which will keep gasoline prices affordable. In exchange, oil companies that want to take advantage of this flexibility can contribute funds to support more affordable EVs for Californians – through a program like Clean Cars for All that provides support for low and moderate income households to make the transition to EVs. This is a win-win solution that doesn’t compromise our health and doesn’t give handouts to an industry that is polluting our communities.

[i] In 1983 California had 40 operating oil refineries with a combined capacity of 2.3 million barrels per day (MBPD). By 2025 the number of refineries had fallen 65 percent to 13, but their combined capacity had fallen just 30 percent, to 1.6 MBPD. The average throughput of a refinery in this timeframe more than doubled.

[ii] Market power problems in California’s gasoline market are not limited to oil refining, as Professor Severin Borenstein has explained in his work on California’s Mystery Gas Surcharge. These issues are the focus of the Division of Petroleum Market Oversight, which is an independent agency within the California Energy Commission, created in 2023 and responsible for oversight, investigations, economic analysis, and policy recommendations regarding the transportation fuels market. A recent post from Stanford economists also addresses the implications of the Valero Benicia refinery closure on gasoline prices in California, including recommendations on how to prevent further gasoline market consolidation.

[iii] For more discussion of repurposing physical infrastructure see the Analysis of The Valero Benicia Refinery Closure on Gasoline Prices in California by two Stanford economists, which discusses the potential to convert the Valero Benicia refinery into a product terminal, which would involve converting pipelines and storage tanks currently used for crude oil to use for gasoline. Another relevant proposal is discussed in the San Francisco Bay Area Refinery Transition Analysis by Christina E. Simeone and Ian Lange for the Contra Costa Refinery Transition Partnership. This analysis discusses the potential conversion of excess capacity in the crude oil pipeline network in California to transport refined fuels, which would provide a direct pipeline connection between Los Angeles and Bay Area markets that currently rely on more costly marine tankers.

[iv] The EPA MOVES model we used for this study is likely to overestimate emissions from more recent cars, because it reflects science based on a test program that was conducted a decade ago. Updating the models and the underlying data sets would allow for a more accurate assessment, which should form the basis for a longer-term update to fuel regulations. Emissions from older cars may be underestimated, since it is more likely these cars will have emissions systems that have degraded and are not functioning as designed.