Coal has been on its way out in New England for years, with coal generation dropping more than 90% in the decade leading to 2017. The shuttering that year of the region’s largest coal plant left only a few coal-fueled stragglers, which closed one by one.

And now, New England’s last coal plant—Merrimack Station—has just closed. Here’s why, and a look at where things go next.

Coal’s rise and fall

The first generator at the Merrimack Station power plant in Bow, New Hampshire, fired up in 1960. The second one arrived in 1968. Six decades of operation meant the plant was long in the tooth, even by the standards of the aging US coal fleet.

But it wasn’t age, per se, that led to the plant’s demise. It was economics.

When a regional electric grid operator is looking to serve electricity demand, it calls on the cheapest power plants first for electricity. As demand increases in a region, it works its way through increasingly more-expensive ones. The economics of coal generation have been collapsing for years, in the face of not just the rise of gas generation, but the advent of larger and larger amounts of increasingly cheap solar and wind power, and energy storage. Being among the most expensive options has resulted in coal plants getting called on less and less for power.

Merrimack Station’s decline mirrored what has happened with coal across the country, with the plant getting called on very little in recent years. A coal plant could, in theory, run almost the whole year round, meaning it has a high capacity factor—the hours it is used divided by the number of hours in the year. While Merrimack Station’s capacity factor was 70-80% two decades ago, though, it didn’t crack the 8% mark in any of the last six years. In 2024, one of its two generating units operated for a total of only 25.4 hours, and the plant as a whole accounted for less than a quarter of 1% of the electricity generated in New England.

The economics for the plant owner got even worse when, in 2023, Merrimack Station for the first time failed to secure a contract in the region’s forward capacity auction, for next year. The capacity market is the mechanism that pays power plants to be ready to fire up, even if they don’t end up being needed. Merrimack Station lost out to other, cheaper sources for meeting high electricity demand, such as other fossil fuel plants, nuclear, renewable energy, and customers willing to dial back their electricity use during the “peak-iest” times.

But electricity isn’t the only thing that comes out of fossil fuel plants like Merrimack Station. Even with the addition of pollution control equipment over the years, the plant continued to burden the surrounding community with its emissions. And its carbon pollution declined only because its generation did: in its peak years two decades ago, the plant emitted the equivalent of as much as 800,000 of the average gasoline-powered cars of today. While the electricity might have been welcome, the pollution never was.

What takes its place?

In recent years, Merrimack Station had been called on for electricity primarily in the cold season. Winter months accounted for eight of the 10 months of highest use of the plant over its last five years. In its last three years, even when Jack Frost hit the region particularly hard, its monthly capacity factor hit 30% only twice.

It’s increasingly evident, though, that New England in particular has a much better, cleaner, cheaper response to electricity demand during winter storms: offshore wind power. Winter storms tend to come with hefty winter winds, which drive up electricity demand. But they also provide loads of kinetic energy just waiting to be turned into electricity by offshore wind turbines.

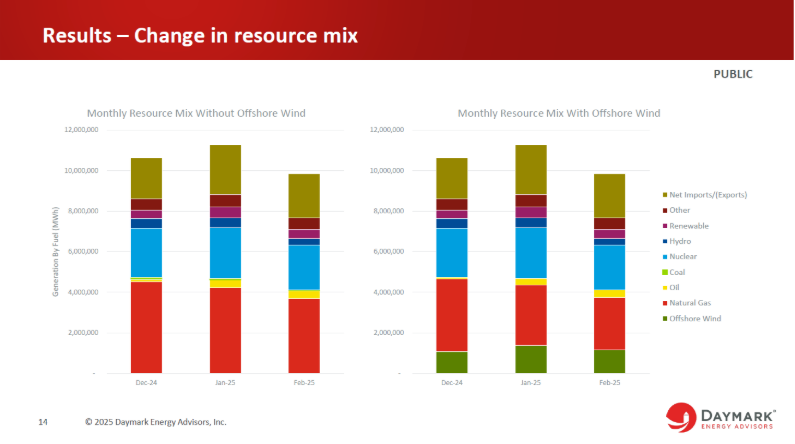

That strong correlation between peak demand and high levels of potential offshore wind generation is visible in the graph below from a recent analysis of the economic value of offshore wind for the region. That correlation means that turbines will be well positioned to supplant not just the small amount of coal generation from Merrimack, but generation from oil peaking plants, which are also expensive and highly polluting, and from gas plants–you can see the offshore wind in green, doing away with the share otherwise provided by coal (the very thin strip in light green) and eating into the shares from oil (in yellow) and gas (in red).

Source: Daymark Energy Advisors 2025

Because they drive the grid operator to turn to the most expensive generators, those peak periods driven by extreme winter weather can significantly drive up the cost of electricity. By displacing that other generation, offshore wind farms can save households money on their monthly electric bills even taking into account that those facilities are more expensive to construct.

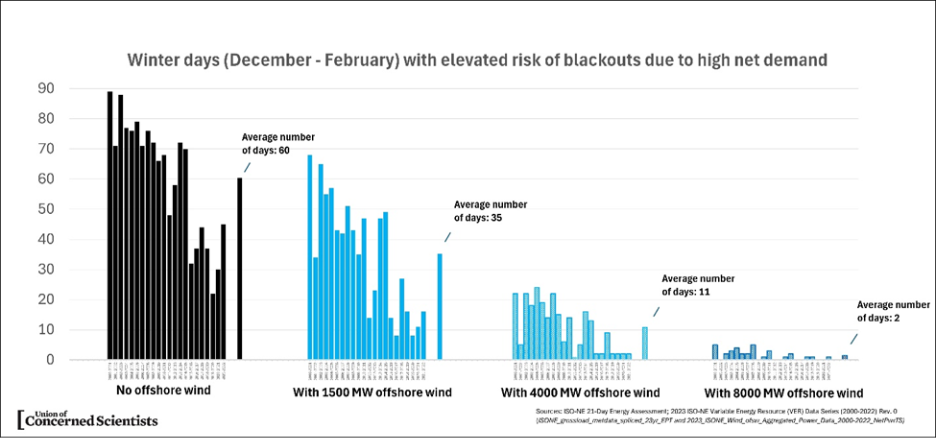

Those winter peaks also represent periods of high risk of power outages, as gas plants (that currently supply half of the region’s electricity) get outcompeted for gas supplies by homes and businesses using gas for heating, and as backup oil plants run out of limited onsite fuel. That means that having a solid amount of offshore wind capacity can dramatically reduce the demand-driven risk of a winter blackout (see below).

Source: UCS 2024

Meanwhile, the ever-growing cadre of willing solar arrays in New England is doing a bang-up job of meeting the summer peaks that Merrimack might once have been called on to help with.

The future gets clearer

New England is done with coal plants.

Aside from a paper mill in Maine that occasionally feeds coal into the generator usually fueled by its own waste products, the region’s remaining connection to the fuel is solely via its neighbors that still have some coal generation, and the connections between the different regional electricity grids. Coal can be in the mix of power that comes into New England over those lines (and coal pollution can also cross into the region).

This retirement is a watershed moment. The fact that New England’s last coal plant was used very seldom before it was gone for good is a testament to the changing face of electricity generation in the region and the country. The fact that its power output will be easily replaced with cleaner and cheaper sources shows how far innovation and scale in renewable energy and energy storage have come.

Some of that replacement may happen at the very site of the now-closed coal plant, restoring some of the jobs and tax revenue that disappeared with the plant: the owners of the Merrimack Station site are looking to install solar and storage there.

And there’s a lot more transformation to come.