Investing in public transit is crucial for our communities, public health, and addressing the climate crisis. But after decades of disinvestment, systems across the country are again feeling the squeeze, facing fiscal cliffs that jeopardize their futures. All the while, still over half of the country does not live near any transit whatsoever, and many less live near transit with high frequency and quality.

Now, Illinois is in the headlines – not just for its battle with the Trump administration over National Guard deployment and inhumane immigration enforcement, but also for an impending funding cliff for public transit that would leave people stuck with service cuts and fare increases.

This follows decades of underinvestment, inflationary pressures, and a transit labor shortage that has hit transit across the country particularly hard after the pandemic. In Chicagoland, fares would increase by 10% at the beginning of 2026, followed by cutting services for people with disabilities (paratransit) and an overall service cut of at least 21%, the largest cuts to CTA in modern history. Downstate, 54 transit agencies in rural areas and smaller cities would face the same specter of financial challenges leading to drastic service cuts.

Illinois needs at least $1.5 billion for better public transit

Chicagoland has the country’s third biggest transit system, providing over 1 million trips a day on average. In the city, around one in five workers use transit as their main way of commuting, and many more people in the region use or benefit from the access and broader benefits provided by the system – including its 13x return on economic investment and billions in avoided car ownership costs.

Yet transit in the region, as it is, has not been enough. Using the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s Housing + Transportation Affordability Index, 47% of people in the region live with unaffordable housing and transportation costs. Transit in Chicagoland has recently recovered to pre-pandemic service levels, and that has kickstarted an upward trend in more people riding transit again.

And this doesn’t just affect Chicagoland – in the state, 54 other public transit agencies provide 30 million trips annually—for example Peoria, Champaign, Springfield transit agencies would face stalled projects and service cuts.

Advocates and public agencies have been sounding the alarm bell for years now. The region’s metropolitan planning organization, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP), put together the Plan of Action for Regional Transit in 2023, recommending a transformational investment of $1.5 billion annually in new operational support for the region and at least $400 million annually in complementary capital investments.

Transit agencies, the Illinois Clean Jobs Coalition, and the Labor Alliance for Public Transit have united under this $1.5 billion ask. The Regional Transportation Authority has said that this would reduce transit wait times in the Chicago region by half. The current legislative package proposes at least $1.5 billion across the state, with $220 million going to downstate (non-Chicagoland) transit agencies. By our analysis, this would be able to support 35% more transit service beyond 2019 levels in 2026.

Illinois legislators face a decision point – will they pass a bill to raise the funding needed for the transit the state needs or will they let it falter?

Three principles for raising transportation funding

States all over the country have been trying to answer the question of how to fund public transit, but in making this decision, it’s important to ground us in a couple of general principles (drawn from Massachusetts transportation advocates).

- Does it incentivize good things, such as climate-friendly behavior and investments?

- Does it disproportionately impact marginalized communities?

- Are there ways to mitigate negative impacts?

Let’s take the proposed retail delivery climate impact fee as an example. As proposed, it would be a flat $1.50 charge on retail deliveries delivered by car or truck, with exemptions for groceries, medications, and purchases from small businesses. This is estimated to generate $1.1 billion annually across the state, which would singlehandedly not only bring transit back to normal, but also contribute to a majority of the 35% transit service growth noted above.

- Good incentives? With the growth in e-commerce, online delivery services, and the whole freight sector, this fee can help disincentivize unnecessary deliveries and compensate for their climate impacts with an investment in public transit. Studies have shown that people indeed change their behavior based on changes in shipping fees and structures (i.e. ordering more to get free shipping can really pique our interest),

- Disproportionate impacts on marginalized communities? Data is quite limited on online delivery behavior by demographics, but research using the National Household Travel Survey has shown that while e-commerce has expanded generally, disparities in use still exist by income, race, education, and employment status. One key concept is regressive taxation, where low-income families are taxed a greater percentage of their income than wealthy families, versus the opposite, progressive taxation, where those with greater capacity to pay contribute more to the public. This is just a bellwether for fairness – even a neutral/flat tax doesn’t account for the fact that lower-income households spend a greater percentage of their income on necessities, so is making them pay the same percentage of their income fair?

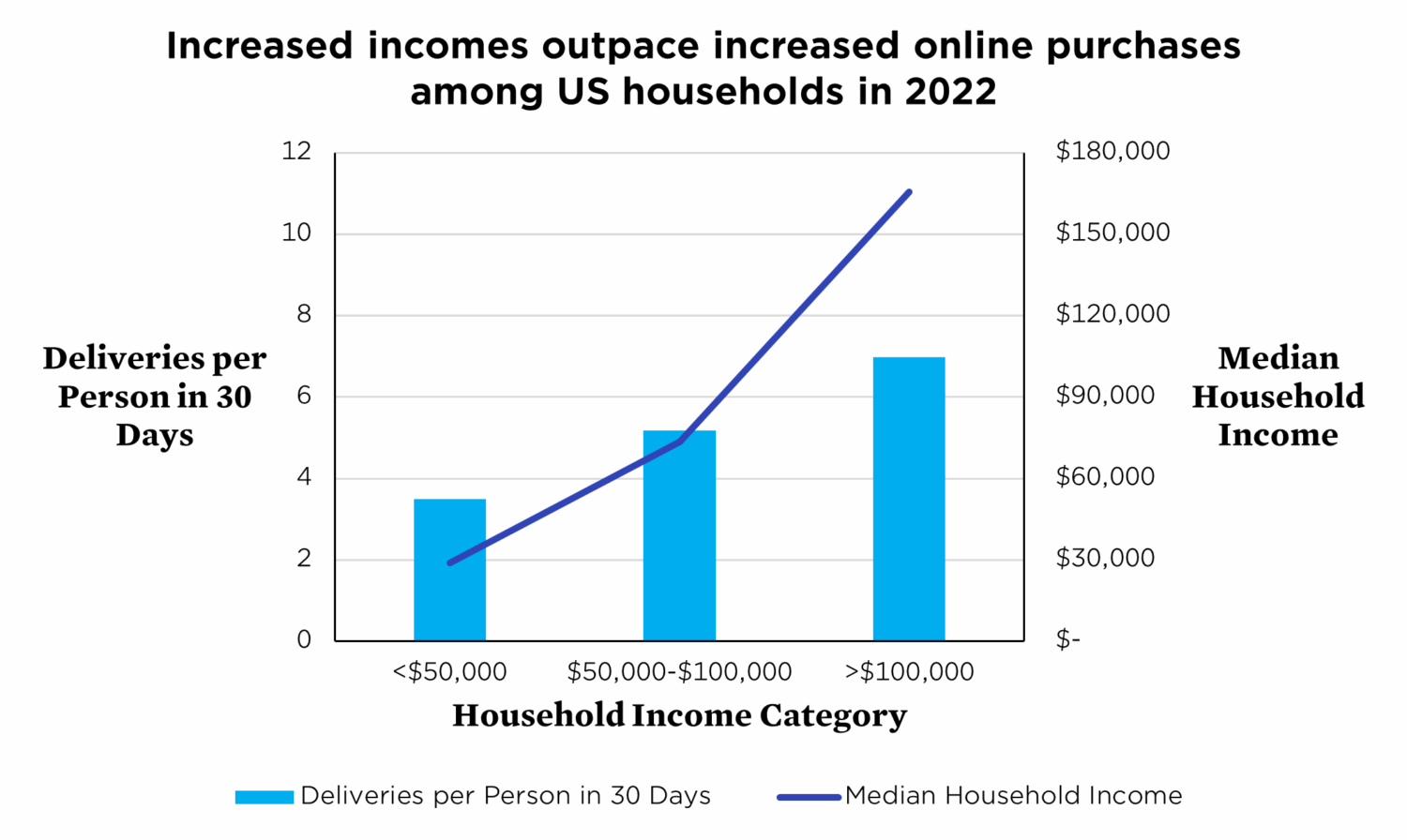

Taking our own look at the 2022 data, we find that people in households >$100,000 make around twice as many delivery purchases as people in households making <$50,000, meaning they would pay twice as much in delivery fees, despite having more than twice as much income. This kind of effect is well known – taxes related to sales or consumption are generally regressive, while taxes related to income or corporate profits can be more progressive.

- Ways to lessen the bad impacts? Exemptions for groceries and medications do slightly reduce regressivity, since the biggest disparities by income come from discretionary items. Other ways to lessen inequitable impacts could include a percentage-based fee (to raise the same amount of money in IL, this would be set around 3%). Using order size is another way, since higher-income people make larger purchases. In Minnesota, their recently implemented retail delivery fee applies only to orders over $100, but this has significantly cut their projected revenue by at least 50%. WA estimates that an exemption on orders under $75 would reduce total revenue generated by half.

Or take the proposed 10% transportation network company (e.g. Uber or Lyft) fee for trips that start or end in the City of Chicago or collar counties, raising $194 million dollars for transit. This would align these services with their unaccounted impacts on global warming emissions and competition for transit ridership. On the consumer front, people with higher incomes but also people with disabilities take more TNC trips. On the worker side, drivers are more likely to be people of color or immigrants who are already facing many other attacks on their existence in public space. To mitigate these disparities, legislators could consider exemptions for accessible trips or credits for trips in low-income areas.

Most sources of public funding, for transportation or beyond, are unfortunately regressive by income. While some of that can be made up for by spending public funding in ways that progressively benefit lower-income communities, this is a gaping hole in how we fund our public services.

Progressive revenue sources are needed, but hard to come by

Illinois is the state with the 8th most regressive tax system in the country – with all but 8 states having tax systems that wind up taxing people with lower incomes at a higher rate than people with higher incomes. Coalitions like the Illinois Revenue Alliance have been advocating for a package of progressive revenue sources to fund public services ranging from immigrant services, schools, public transit, healthcare, and more. Some of these include:

- Corporate payroll tax: Because transit benefits regional and state economies broadly, raising revenue from the corporations that benefit can be a promising place to fund transit. For example, places like New York City (0.55-0.9% depending on total firm payroll) and Oregon (0.1% and ~0.8% extra in Tri-Met and Lane County transit districts) have specific taxes in place to fund public transit. However, it is difficult to target this to avoid regressive impacts (i.e. NYC’s tiered system targets larger firms, but that may not align with larger worker incomes), and flat rates only ensure neutrality. fairness – even a neutral/flat tax doesn’t account for the fact that lower-income households spend a greater percentage of their income on necessities, so is making them pay the same percentage of their income fair?

A more targeted income tax could ensure progressivity. In 2022, Massachusetts voters passed the Fair Share Amendment, a 4% surtax on additional annual income beyond $1 million that has already been investing billions in education and transportation. This has brought in more than $2 billion than what was expected, and there are more millionaires in the state than before the fee was passed. - Corporate income tax: The corporate income tax generally targets corporate profits from dividends and capital gains rather than wages, which generally ensures progressivity. At the federal level, the Trump Administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017 gutted it from a top rate of 35% to 21%, and this provision was extended in the most recent reconciliation bill. This tax already exists in most states, including in Illinois, and raising it from 7% to 7.92%, as is maximally allowed, could raise $830 million per year.

- Mark-to-market tax: Sometimes called a tax on unrealized capital gains, one way to level the tax playing field to have the wealthy pay their fair share is by ensuring that income from appreciating corporate stock or other capital assets is captured for the wealthy just like all other income everyone else makes. At the federal level, versions of this were proposed by the Biden Administration’s FY23–25 budget proposals, and most recently in Congress as a billionaire minimum income tax, which would make the tax code more equitable. In Illinois, charging the same state income tax that applies to all other income for the appreciation of billionaire assets could raise around $840 million per year.

Progressive tax sources are shown to be not just important for fairness and raising revenue for public investments, but also popular across race, zip code, and political divides. A 2025 Pew Research Center poll found that more than six-in-ten U.S. adults say tax rates on large businesses and corporations should be raised.

Public transit needs investment, time to speak up

The state deserves robust investment in public transit that comes from equitable sources, and extensive research has shown both why and how. With the state legislature’s veto session ending at the end of the month, and transit service cuts to come if legislators don’t come up with a solution, the clock is ticking until the region grinds to a halt. What’s particularly challenging about this and any state fights is the dynamic where legislators across the state must agree on funding sources even when transit is used differently in different regions. The reality is that the entire state benefits when all of us, regardless of whether we live in metro areas or rural communities, have access to reliable, public transit systems.

That’s why Illinois legislators across the state need to hear from you. Legislators need to pass a bill with at least $1.5 billion in new annual transit funding, while also including provisions to mitigate disparate impacts. It’s time to act—to invest in affordable, clean transportation options that support economic vitality, public health, and wellbeing in communities across the state.