Michigan communities can breathe easier this winter knowing that the state just streamlined the process to connect affordable and reliable clean energy, thanks to an update to utility DTE’s interconnection procedures.

When a customer is seeking to connect a distributed energy resource (DER) such as rooftop solar to the grid, their electric utility’s interconnection procedures detail the steps to ensure it is done legally and safely. The procedures also govern requirements for DERs to be eligible for incentives such as net metering.

In April 2023, Michigan updated its statewide rules (the MIXDG rules) for the first time since 2009, requiring each utility to revise its procedures and submit them to the Michigan Public Service Commission (MPSC) for review and approval. The MPSC found that each utility needed to make some changes—but especially DTE, the only utility whose application was converted to a contested case complete with expert testimony, cross-examination, and legal briefs.

UCS and our partners in Michigan intervened in the case, where I filed testimony focusing largely on how “export-limited” DERs, described below, are handled. Later, we worked directly with DTE on a settlement agreement to resolve the complicated technical issues of the case. In an MPSC ruling last week, the agreement was accepted, with DTE’s updated procedures taking effect immediately.

The approved procedures mark a major step forward for clean energy interconnection, making the process clearer, fairer, and more consistent with modern standards and technology, paving the way for more clean energy to come online.

In this blog, I’ll discuss export-limited DERs, how they’re addressed in the updated procedures, and what this means for distributed, clean energy in Michigan.

What are export-limited DERs?

An export-limited DER is a system where the maximum output to the grid is constrained to be less than the DER’s full capacity. This may be needed if the first step in the procedures, the “penetration screen,” indicates that the grid has insufficient hosting capacity for the proposed DER. Adding power to the grid above its hosting capacity could compromise the safety and reliability of the grid.

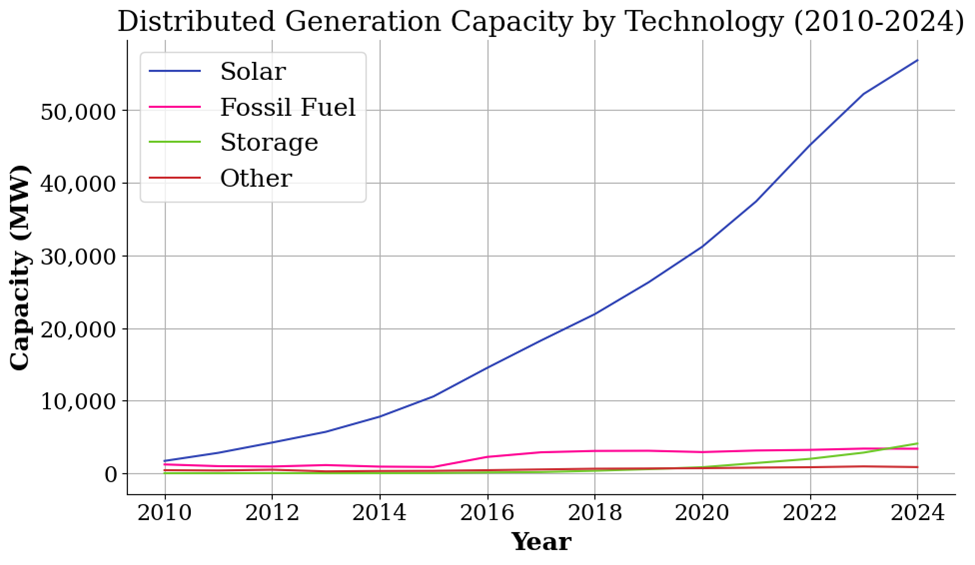

Historically, penetration screens have assumed a worst-case scenario, comparing the nameplate capacity of the DER (its maximum rated power) to the peak demand of the neighborhood electric circuit where it will connect. This made sense for DERs like fossil fuel generators that can provide their full output at any time, but it’s excessively conservative for solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, the predominant type of DER being connected today.

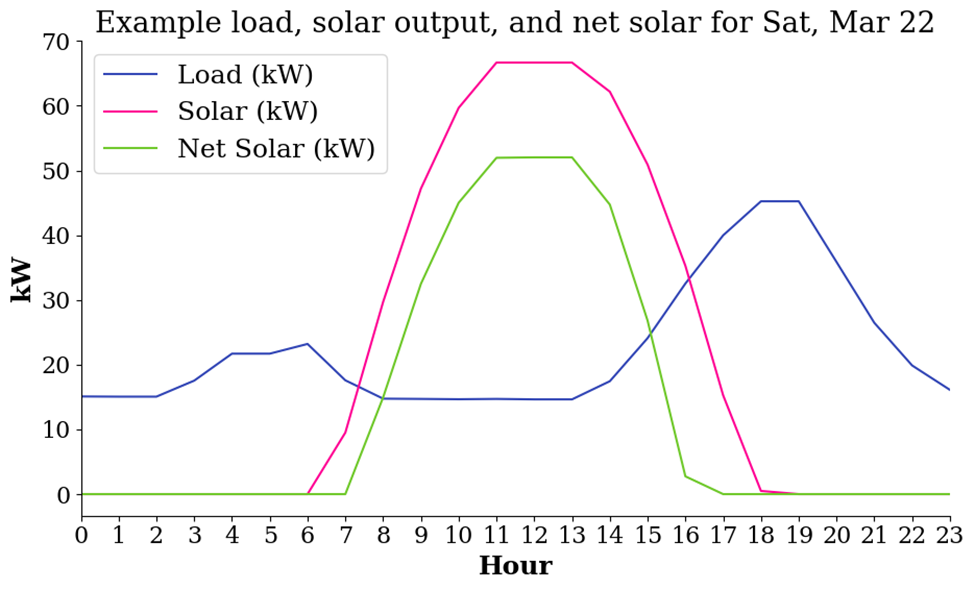

To understand why, consider a typical 50 unit apartment building in Detroit with 80 kilowatts (kW) of rooftop solar panels. On a sunny summer day, the highest output from the solar is about 60 kW—but at the same time, the building uses about 100 kW, meaning there’s no net export to the grid. In fact, the highest net output during the year is about 50 kW on a typical spring day, shown below.

While the nameplate capacity of this hypothetical system is 80 kW, in practice it almost never exports more than 50 kW to the grid, as the building’s own load is typically consuming everything above that amount. If the project faced a hosting capacity limit of only 50 kW, the building could still connect the 80 kW array (and get all the benefits of the larger system), by constraining (or limiting) what it exports to the grid to 50 kW.

Power control systems enable robust, affordable export limiting

Until about 10 years ago, most options for export limiting were expensive and complicated, and only made sense financially for the largest DERs. But by 2016, manufacturers of solar inverters had begun offering built-in export limiting using power control systems (PCS).

PCS technology has now been on the market for close to 10 years, with California being the first state to allow its use in 2016. The 2020 edition of the National Electrical Code introduced rules governing use of PCS, and was coordinated with changes to UL 1741, the safety standard for solar inverters. Several other states have since approved export limiting with PCS, including Arizona, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, and Nevada.

One challenge which PCS introduce is the risk of “inadvertent export,” the phenomenon when a PCS momentarily exceeds the export limit. If the load behind the PCS suddenly decreases (such as air conditioning cycling off) or if the connected generation suddenly increases (such as clouds parting above the solar array), it may take a moment for the PCS to measure and respond to the change. Without limits or safeguards against inadvertent export, this momentary spike in exported power can result in damage to grid equipment.

Fortunately, the MIXDG rules include two critical safeguards against this risk. First, consistent with UL 3141 (the relevant safety standard), any PCS must be certified to respond to inadvertent export within 30 seconds. Second, if any part of the PCS malfunctions, the DER must stop exporting any energy to the grid.

DTE sought to restrict the use of PCS

Despite these safeguards, in its original August 2023 filing, DTE sought to place three restrictions on PCS in its proposed procedures:

- Penetration screens would be based on nameplate capacity, not export capacity, eliminating the principal motivation to use a PCS.

- The time limit for a PCS to respond to inadvertent export would be 200 milliseconds, instead of the standard 30 seconds. This is excessively conservative and would make it challenging to find an approved PCS.

- The nameplate capacity of a DER with PCS would be limited to no more than 20% above the export capacity. But in typical solar-plus-storage systems, the solar and battery are each sized to meet the building’s full load, making the nameplate capacity roughly twice the PCS-limited export capacity—far above the proposed limit.

In testimony, DTE’s witness did not provide evidence of the specific risks or why these restrictions are necessary.

DTE’s proposed limits were excessive and contradicted the rules

In my testimony, I argued that the actual risk of damage from inadvertent export is significantly lower than DTE assumed, making the proposed restrictions unnecessary.

I pointed out that because inadvertent export events are triggered only by sudden changes in load or generation, their impact is naturally limited, and simultaneous or repeated events are highly unlikely. Further, the conductors and transformers affected are designed to handle overloads significantly greater than those caused by inadvertent export. This means that the risk of thermal damage to equipment is essentially zero.

I did acknowledge that there is a minor risk of voltage fluctuations caused by inadvertent export. But rather than using the restrictions DTE proposed, I recommended that this risk be mitigated using a simple voltage screen like the one initially proposed in the BATRIES report. This definitive report was developed by a group of researchers and utilities to support standardization of interconnection procedures for batteries and solar-plus-storage DERs. And as the BATRIES report explains, because voltage issues precede other risks to grid equipment, it also effectively screens for those risks.

Further explanation of the minimal risk posed by inadvertent export is provided in a memo from IREC, included as Exhibit CEO-4 in my direct testimony.

Settlement discussions were long, technical, but productive

After briefs were filed in the case, DTE reached out to discuss a settlement. Over several months, we discussed the procedures point-by-point, hashing out the technical details. Ultimately, we settled on a nuanced approach to limited export DERs which eased the restrictions on PCS while addressing DTE’s safety concerns by adding the voltage screen I had proposed.

DTE agreed to base the penetration screen on export capacity and align the time limit on inadvertent export with the 30 second requirement in the MIXDG rules. DTE also agreed to ease the capacity limits, basing them on the rating of the utility infrastructure rather than the DER size. While I still believe these limits should be higher, they are unlikely to affect most conventional projects. I’ve summarized the (fairly nuanced) limits below:

| Project size | Total nameplate capacity limit of all export limited projects on a utility transformer, compared to that transformer’s rating |

|---|---|

| Greater than 1 MW | 120% |

| Greater than 20 kW up to 1 MW | 200% |

| Up to 20 kW | 300% (no individual project may exceed 200%) |

In practice, on a typical residential feeder served by a 50 kVA transformer, the total nameplate capacity of all export-limited projects could not exceed 150 kW if each individual project was 20 kW or less.

DTE is the first Midwest utility to implement a voltage screen for inadvertent export

A key component of the settlement was the addition of the voltage screen that I had recommended, which addressed DTE’s concerns about the risks of inadvertent export.

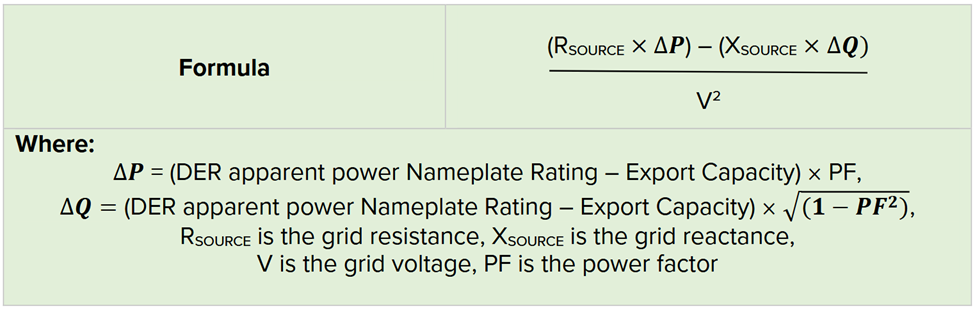

The BATRIES team developed the screen to address a gap in the typical screening process that applies to export-limited projects. The limit for the initial penetration screen (15% of peak load) is set to account for the impact of DERs on grid voltage. But if some portion of the DER capacity is export-limited, it’s possible for voltage to rise above acceptable limits during an inadvertent export event, when the active capacity can momentarily exceed the 15% limit. The voltage screen for export-limited projects addresses this risk by estimating their impact on grid voltage, using the formula below. If the voltage change exceeds 3%, then the project fails the screen and must undergo further study.

We discussed this screen at length with DTE, who ultimately agreed to implement it with a few tweaks. As far as we are aware, DTE is the first utility in the Midwest to implement this screen, and one of only a handful across the US to adopt this sophisticated, rational approach to screening export-limited projects.

Other important wins in the settlement

In addition to this significant accomplishment for export-limited projects, there are several other notable settlement terms:

- Unintentional islanding: DTE originally required costly direct transfer trip (DTT) for all risks associated with islanding, a safety risk occurring when DERs continue generating power during grid outages. The settlement replaces this with a screening process that triggers a study only when needed and allows more cost-effective mitigation options. DTE will also join workgroup discussions which will consider an updated screening approach developed by IREC.

- IEEE 2800 applicability: DTE initially sought to apply the entirety of IEEE 2800—a standard for projects connecting directly to the transmission system—to any project which might impact the transmission system. The settlement narrows this to only the specific clauses relevant to certain projects, giving developers clearer, more appropriate requirements.

- Incentive program eligibility: DTE will now account for solar panel orientation and tilt when calculating annual generation for distributed generation program eligibility, allowing many more projects to qualify for incentives.

Continuing momentum on common-sense procedures

This settlement marks a significant victory for clean, distributed energy in Michigan. Alongside the Environmental Law and Policy Center, the Michigan Energy Innovation Business Council, Advanced Energy United, and MPSC staff, we worked closely with DTE to develop procedures that comply with the MIXDG rules, provide clear guidance for DER projects, and robustly manage the risk of inadvertent export. The support of IREC, the lead author of the BATRIES report, was also critical early in the case.

It was encouraging to see DTE take up this challenge and implement solutions like the voltage screen. We hope to see the company continue to lead in this way, participating in the interconnection workshops and supporting other Michigan utilities seeking to implement this approach.

In the meantime, customers in DTE’s territory who are seeking to implement clean solar energy projects will have a clearer and more reasonable set of procedures to follow when doing so, resulting in more projects being approved more quickly.