In this new era of artificial intelligence (AI), it’s important to understand the basics of AI in order to answer important questions about when it makes sense to use AI tools, how much we should invest in improving them, or whether we should use them at all.

Excitement around AI has spurred a proverbial gold rush of data center development in the United States and globally. This rush-to-build is also driving a corresponding growth in electricity demand. A recent UCS analysis found that, without explicit policies to support clean energy investment, this explosion of AI-driven data center deployment will lead to greater health and climate costs, and likely higher electricity costs for homes and businesses. Although this post will not attempt to answer the fundamental questions posed above, my goal is to give the essential background for an informed discussion about artificial intelligence and its uses. With that, let’s dive in.

What is AI?

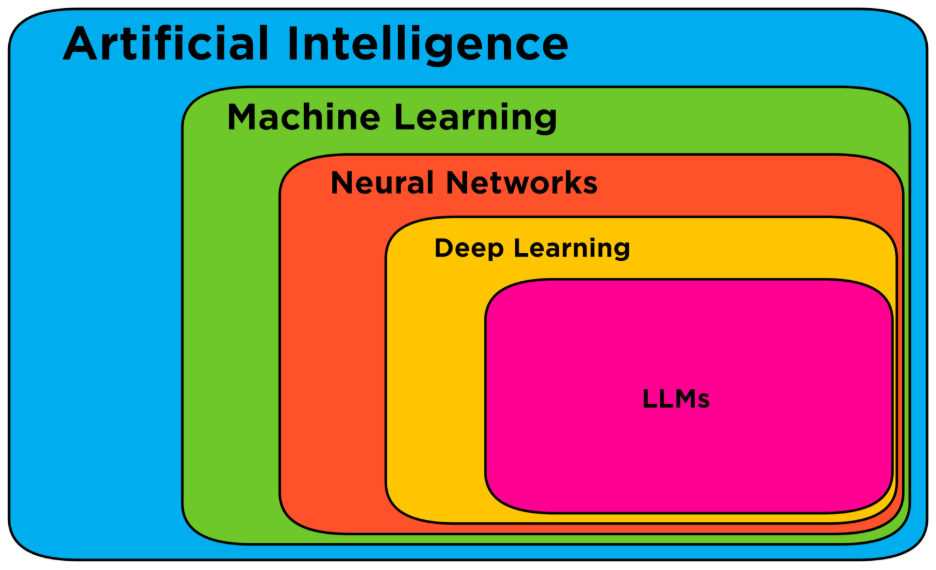

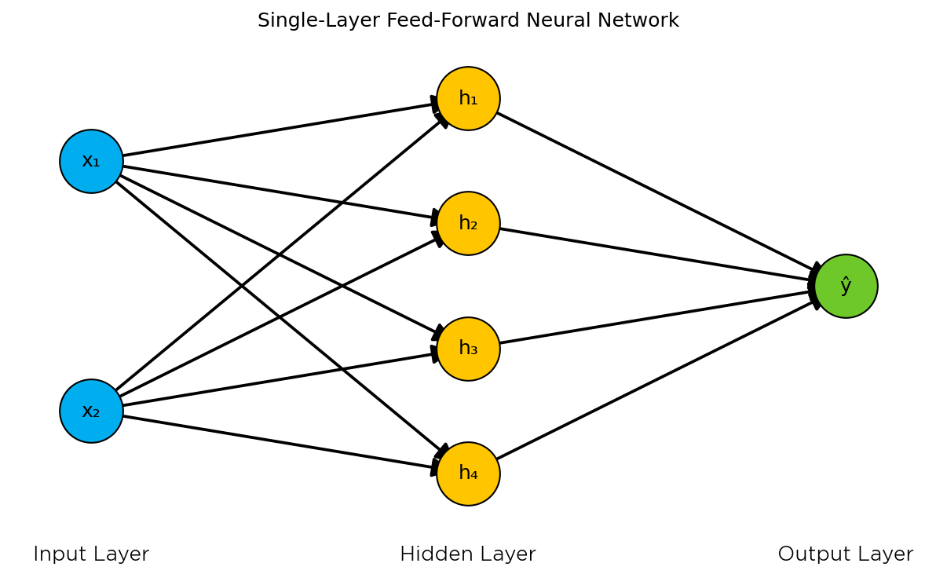

Before I discuss what AI is in a literal sense, I should clarify what is meant by AI more generally. The figure above is a simplified guide to the expansive field of AI. Broadly, AI can refer to any system that attempts to replicate human intelligence. Under the umbrella of AI is the field of machine learning (ML). The idea of machine learning is to make predictions in new situations by applying statistical algorithms to known data. Recommendation algorithms are a popular example of machine learning, used by companies like Netflix or Spotify. There is a veritable zoo of algorithms that vary according to the kinds of data being used and the questions asked of those data. However, one of the most popular algorithms is called a “neural network”—so-called because it was inspired by the neurons in a brain. The figure below depicts a simple neural network.

In a neural network, some input data activates the nodes in the input layer which in turn activate the nodes in the hidden layers in a cascading fashion until it reaches the output layer. Like the way neurons connect and fire in a brain. As the number of nodes (or neurons) increased with additional computing resources, researchers further categorized larger neural networks under “deep learning.” Interestingly, “deep learning” was the buzzword du jour before OpenAI’s ChatGPT 3.5 was released in late 2022, now it is AI. This brings us to large language models (LLMs), which are a specific flavor of deep learning architectures. It is in the context of LLMs, such as ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini, that most readers will be familiar with the term AI. Due to the familiarity with AI via LLMs—and because LLMs are a sub-category of neural networks—the rest of this blog post will focus only on AI in those contexts.

Now, in a literal sense, AI is comprised of a large file of numbers called “weights” and “biases” that correspond to assumptions. For the sake of this discussion, I’ll stick to calling them assumptions. These assumptions are stored in a computer’s memory. There are many AI models that you can run locally on a desktop computer or laptop. But popular LLMs like Claude, ChatGPT, or Gemini, can take hundreds of gigabytes (GB) of memory to run, which requires numerous powerful computer chips, known as graphical processing units (GPUs).

Storage vs memory, and why AI models run on GPUs

You might be familiar with hard drives or solid-state drives (SSDs) for storing data on your personal computer. The cost of storage has fallen a lot in the past few years such that you can get a 1TB SSD for around $150 at the time of writing. While this could certainly hold an LLM, storage is not where computers make calculations (at least, not quickly). You can think of storage like a storage locker—a place where you can put things you want to keep, but aren’t using regularly.

On the other hand, computers also have something called random access memory (RAM) which is used to store information your computer needs to access quickly. You can think of this like the counter space in your kitchen. This space limits how many pots you can have boiling or how many vegetables you can prepare simultaneously. For your computer, if you have a lot of browser tabs or programs open at once, that will use up a lot of RAM because your computer must keep track of all of those different tasks. For high-end computers with dedicated GPUs, there is a third type of resource called video RAM (VRAM). VRAM is allocated specifically for intense graphics processing for video games, 3D rendering, and now, AI.

How does AI work?

AI works by taking some input or set of inputs and applying the model’s assumptions to that input. Since computers only comprehend numbers, text inputs are first converted into chunks called “tokens.” These tokens are assigned a numerical value which corresponds to an “embedding” or “vector.” These vectors specify where a word lives in the space of all possible words and encode semantic meaning. Similar to every place on Earth having a unique longitude and latitude, every word has a unique vector coordinate.

An AI model’s assumptions are refined through many iterations in a process called “training” where the model is asked a question and then adjusted based on how close it was to the correct answer. For example, we might ask an AI model to fill in the blank: “An ______ a day keeps the doctor away!” At first, the AI model might answer with something nonsensical, like “penguin.” But, because all words are expressed with vectors, we can figure out exactly how far away the model was from the correct answer in its training data, and, more importantly, how the AI model should adjust its assumptions to get closer to the right word.

This training process can take many iterations, and it requires a lot of data to generate good results. This is why AI companies scrape the entire internet to build their training datasets. Once training is complete, the assumptions are fixed, and the model can be used to make predictions when someone inputs a prompt or another piece of input data (this is often called “inference”). AI companies have not published a breakdown for the amount of energy used by training versus inference. Although model training represents a more computationally intensive upfront cost, the share of AI workload devoted to inference is expected to exceed that of training in the near future, if it hasn’t already.

Why do we need data centers to power AI?

So, why do we need data centers to power AI? The answer comes down to scale. GPUs get their speed from the ability to do many calculations in parallel (akin to having multiple checkout lines at a grocery store). However, as mentioned earlier, modern AI models need a tremendous amount of memory.

OpenAI’s GPT 3.5 model has 175 billion assumptions, requiring around 350 GB of memory, and GPT 5 has an estimated 1.7-1.8 trillion assumptions. The most advanced commercially available GPUs (at the time of writing, NVIDIA’s H100 GPU) have 80 GB of VRAM. One instance of GPT 3.5 would require 5 GPUs! For context, a higher-end gaming computer typically has 10 GB of VRAM. With approximately 900 million weekly visitors to ChatGPT as of December 2025, it’s not hard to see why OpenAI, one the major AI companies, owns a reported 1 million GPUs.

Housing these massive collections of GPUs requires specialized facilities ranging in size from enterprise data centers, for smaller companies and organizations, up to hyperscale data centers operated by tech giants. These hyperscale facilities can draw upwards of 100 MW of power, which is enough to power a small city. The electricity demand from data centers exploded by 131% between 2018 and 2023, primarily motivated by AI training and deployment. Future AI-focused facilities are planned at the gigawatt scale.

What does AI do?

What AI does is make predictions based on some input and its built-in assumptions. This means that AI systems do not “know” things. You could ask an AI model “what color is the sky?” and it might say “blue,” but only because its training data included sufficient examples of the sky’s relationship to the color blue. What color is the sky? According to an AI, it is blue (with 98.5223% probability).

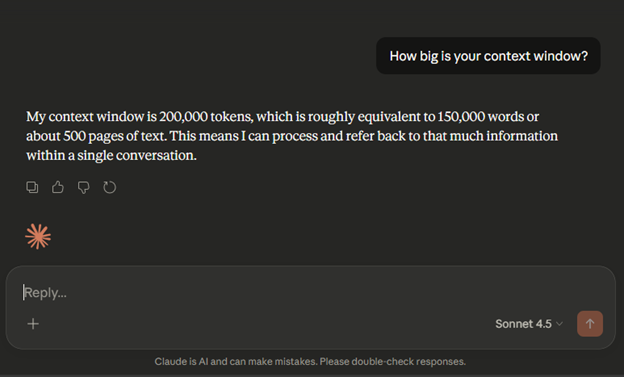

AI models also do not learn continuously. As I mentioned earlier, after an AI model has been trained, its assumptions are static. If an LLM appears to “learn” things about you through conversation, it is because that information is still within its context window (the maximum amount of information that an AI can process at one time).

Finally, AI models are not (yet) general intelligence, meaning that models don’t exceed human cognitive abilities across all tasks. Different machine learning models may perform well on some tasks but not on others. For example, LLMs have proven exceptional at generating text and bits of code but are unlikely to be useful for predicting wind speeds or stock prices. This is arguably the most important lesson from this blog post: that all AI models have limitations, and understanding what those limitations are is critical for making decisions about how AI is used.

Where do we go from here?

Whether it’s drafting emails or generating images with LLMs, filling gaps in historical climate records with AI climate models, or media streaming services recommending your next song or TV show, AI is already affecting the way people work and live.

Despite the incredible possibilities for AI, the environmental and social costs associated with its development and use expose serious trade-offs. The fundamental machine learning algorithms that allow climate scientists to create granular models of the Earth’s atmosphere, or allow energy companies to optimize renewable energy generation, are also driving massive growth in power consumption from data centers in the form of generative AI models, like LLMs. The growth in electricity demand from data centers is also driving up electricity costs to consumers. Understanding these trade-offs, and making decisions about them, should not fall to tech companies alone. It requires all of us.

As the UCS analysis discussed at the outset makes clear, the decisions we make now about the way we power data centers and invest in clean energy will shape the costs and benefits of AI for years to come. The more informed the public is about what AI is and how it functions, the better equipped we’ll be to have these conversations.