Last week brought a dizzying and dangerous official start to summer—or what we call “Danger Season,” the time of year when climate change makes extreme weather more likely and dangerous in the US. From around June 20, a heat dome covered many parts of the eastern US for nearly a week. High temperatures in the upper 90s (°F) through triple digits were common, with densely populated areas like Boston, New York City, and Raleigh, North Carolina feeling oppressive heat index values—the “feels like” temperature—of at least 110°F. About half of the country’s population was caught in the vice grip of extreme heat, and that was in June—early in the season.

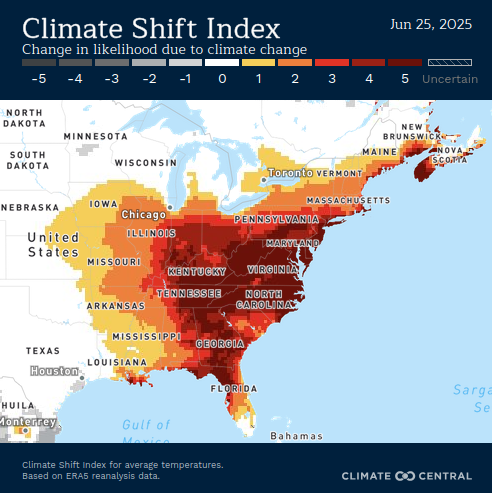

The extreme heat was at least three times more likely due to human-caused climate change, a stark reminder of the added health risks due to the unimpeded advance of climate change on weather extremes. These risks are also compounded by reckless and ill-advised cuts to extreme weather protection resources across the federal government.

across the eastern half of the US had a clear climate signal.

Climate Central

In addition, some of these risks are increased also because the progress made in enacting heat protective measures are not widespread enough to protect the millions of people who were exposed last week to the brutal heat. Millions—and in particular low-income and energy-burdened communities—rely on an uneven and patchy tapestry of heat protective standards for workers, and protections against hot-weather utility shutoffs and utility bill payment assistance. Energy-burdened communities are those where households spend a disproportionately large amount of their median income on energy bills.

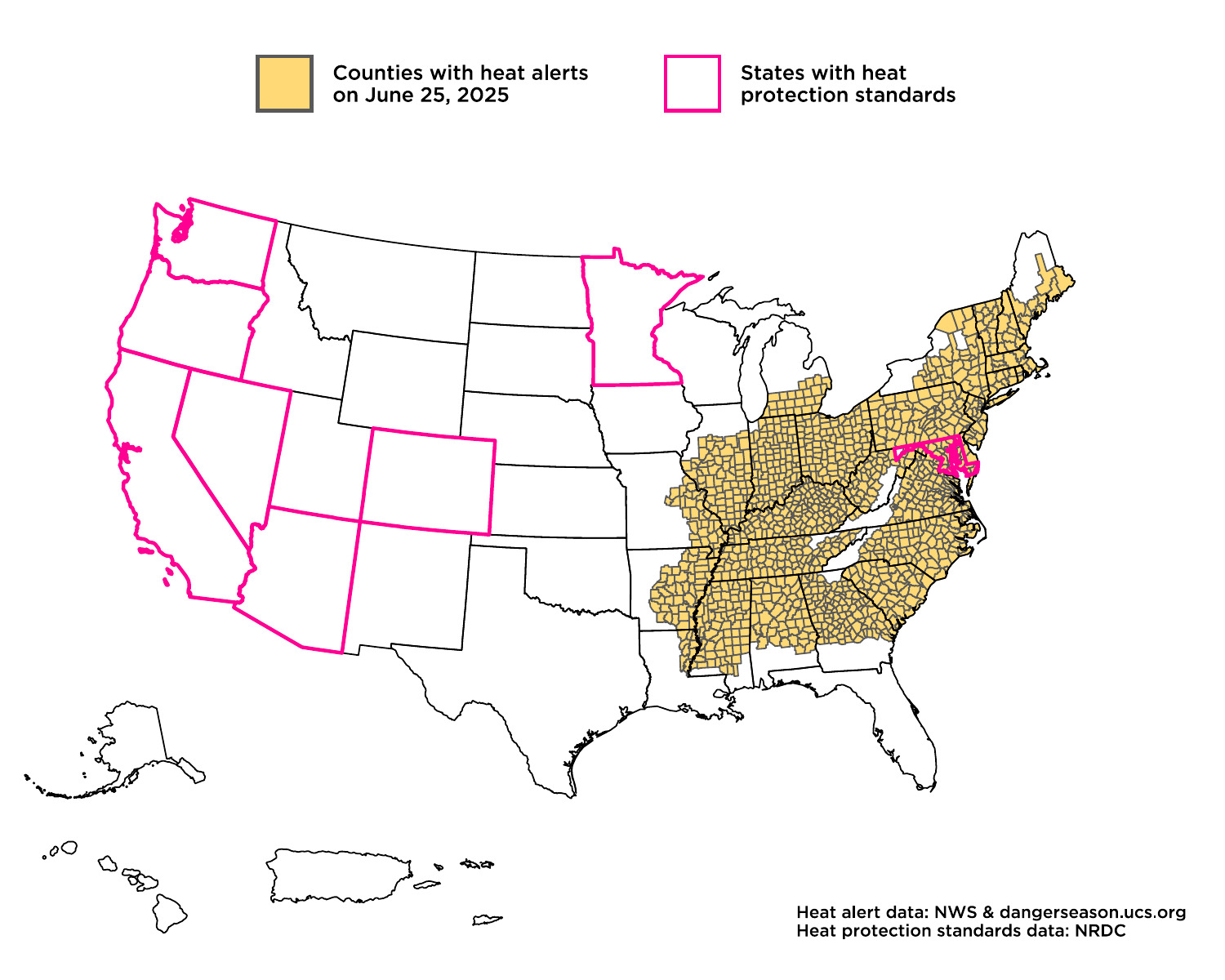

Patchy protections leave gaps in heat safety for workers

Workers, in particular those who do work outdoors, face great risks during extreme heat, but only eight states have protections in place for workers (such as required water breaks and access to shade). The map below shows the states with heat standards for worker protection together with the extent of active heat alerts on Wednesday, June 25, illustrating the dangerous gap workers found themselves in this week. Note that out of these eight states, all but Minnesota include outdoor workers in their protective standards.

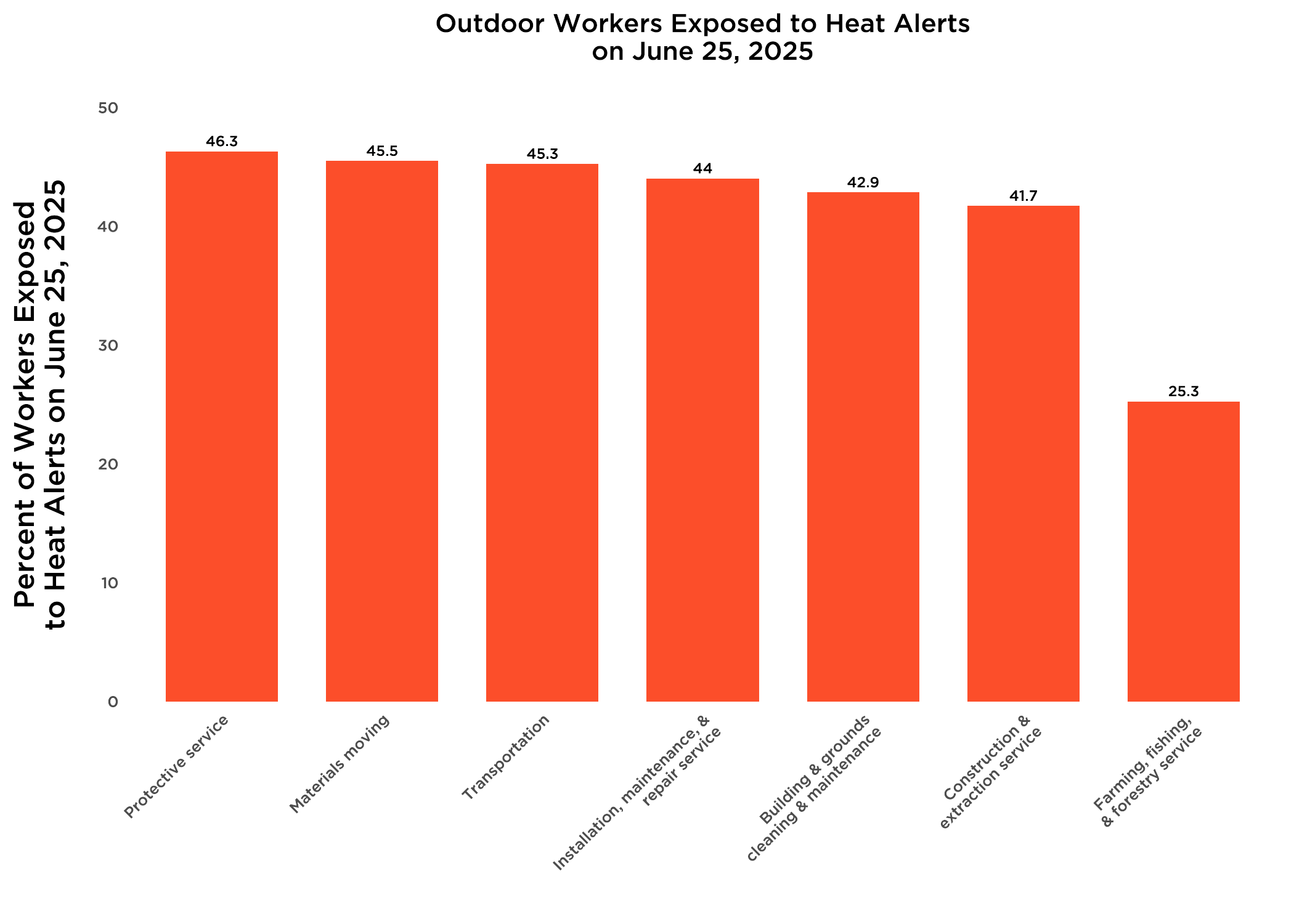

And a significant fraction of outdoor workers across many industries were exposed to dangerous and unhealthy heat across the Midwest, the South, and the Mid-Atlantic. With the exception of farming, fishing, and forestry industries, nearly half of the workers in mostly outdoor employment categories faced extreme heat alerts on June 25.

The glaring need for federal heat protections for outdoor and indoor workers

This is why we need federal heat protections that can provide a national standard across industries and states to protect workers. After decades of calls for action, in 2021 the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) began its rulemaking process to develop heat protection standards to help keep workers safe, a process that typically takes up to eight years). Currently OSHA is holding public hearings on its Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Work Settings proposed rule. However, under the Trump administration, the advancement of this rule is tenuous and underscores why Congress must put these protections into law.

The Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness, Injury, and Fatality Prevention Act (S.2501 / H.R. 4897) would mandate that OSHA release the rule in established timelines and adds additional accountability. A lack of federally-mandated access to water, rest, and shade means workers continue to get sick or die because of extreme heat, even though commonsense measures could prevent these harms. Back in the 1950s, the military understood the need for such heat protections standards when enlisted personnel experienced high rates of heat illnesses during training. Every worker deserves to come home safely at the end of their shift, especially when climate change-driven heat is record-shattering and so dangerous.

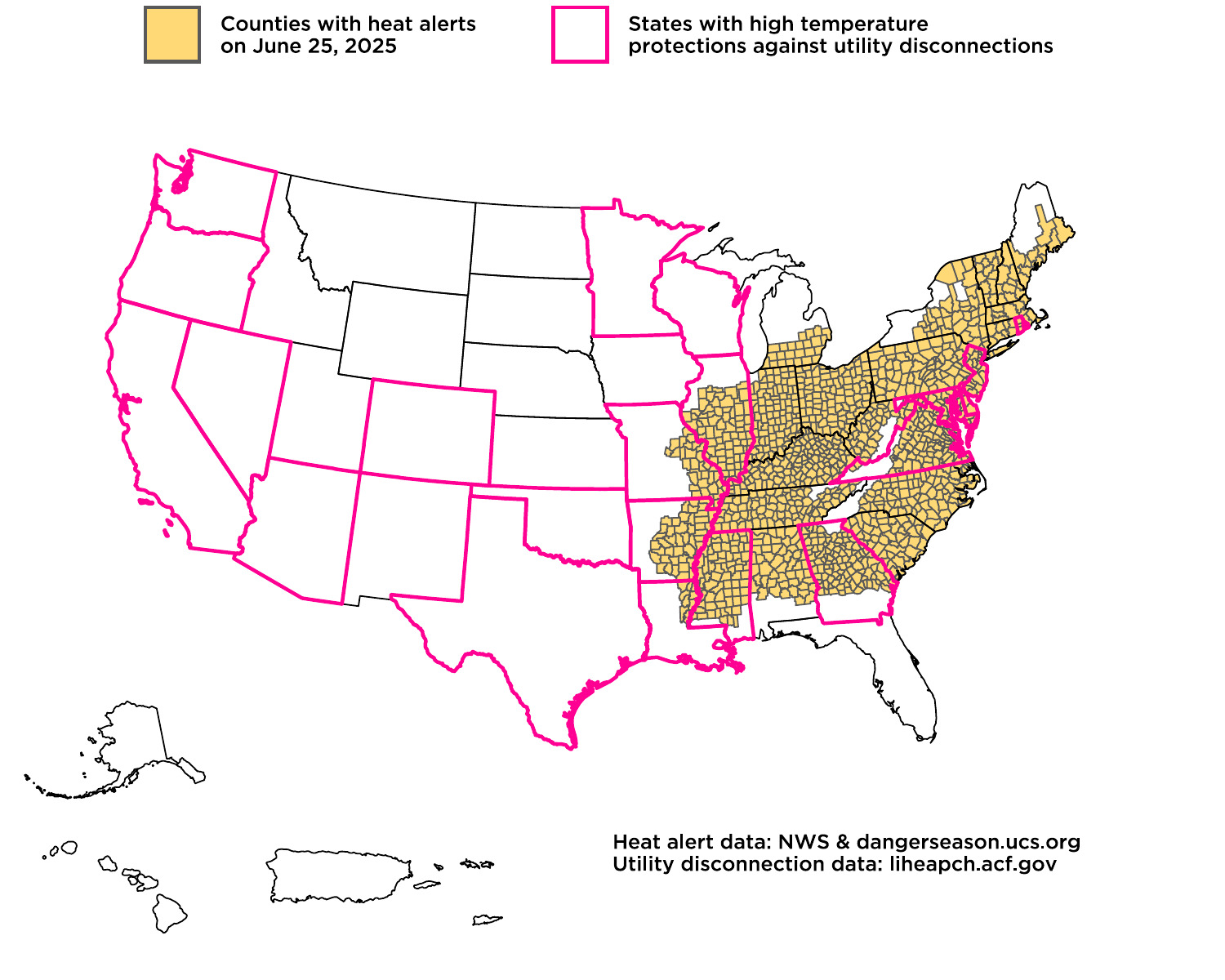

Uneven protections against hot-weather utility shutoffs

Utility shutoffs during heatwaves are another way that individuals in vulnerable situations face elevated risks during extreme heat this year. Households with fewer resources may not have air conditioning or may not be able to pay the costs to run it. Such households are often called “energy-burdened,” meaning that heads of households spend a significant amount of their budget on energy costs. Energy burdens are caused in part by regressive policies that become worse for people living with low income.

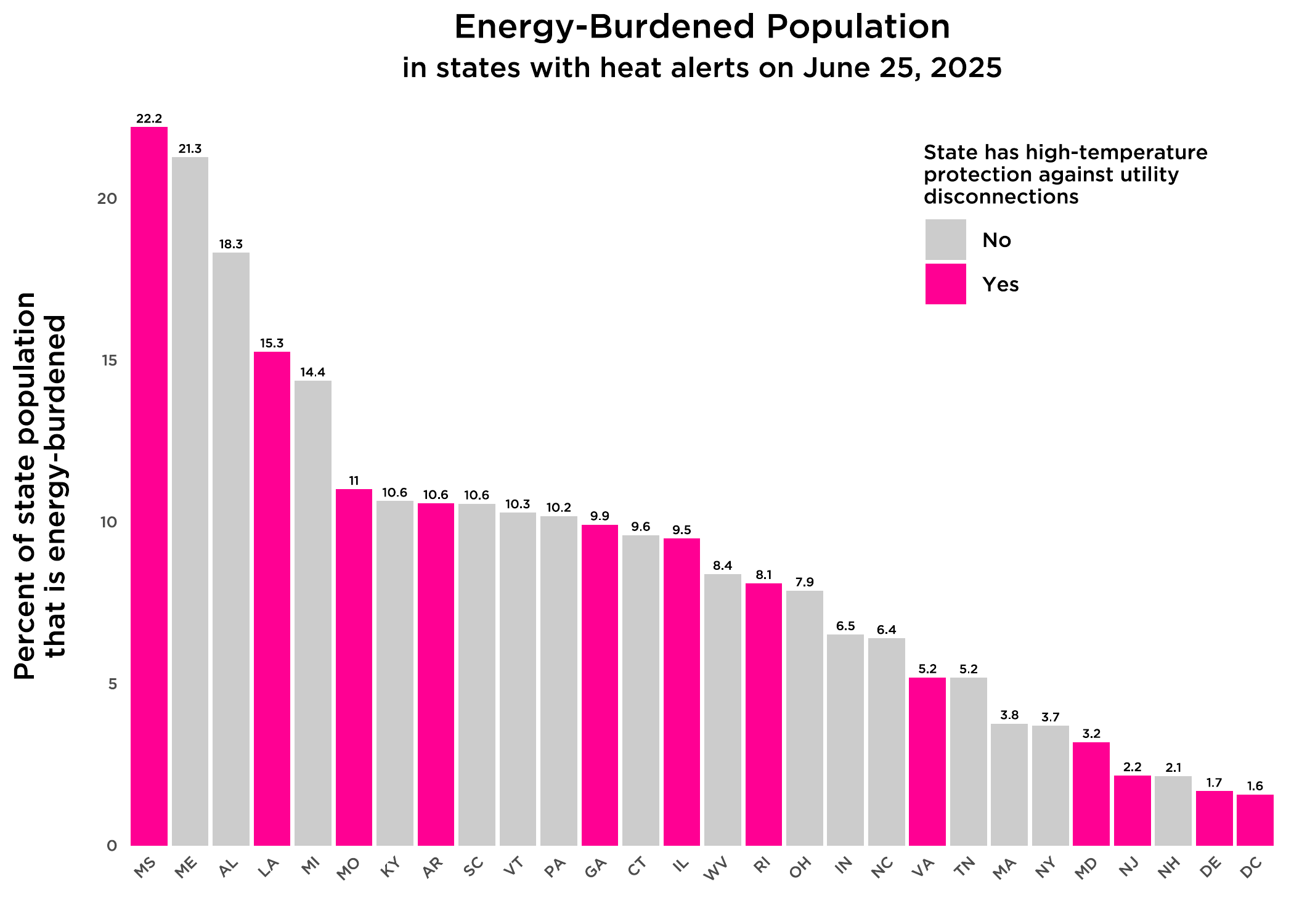

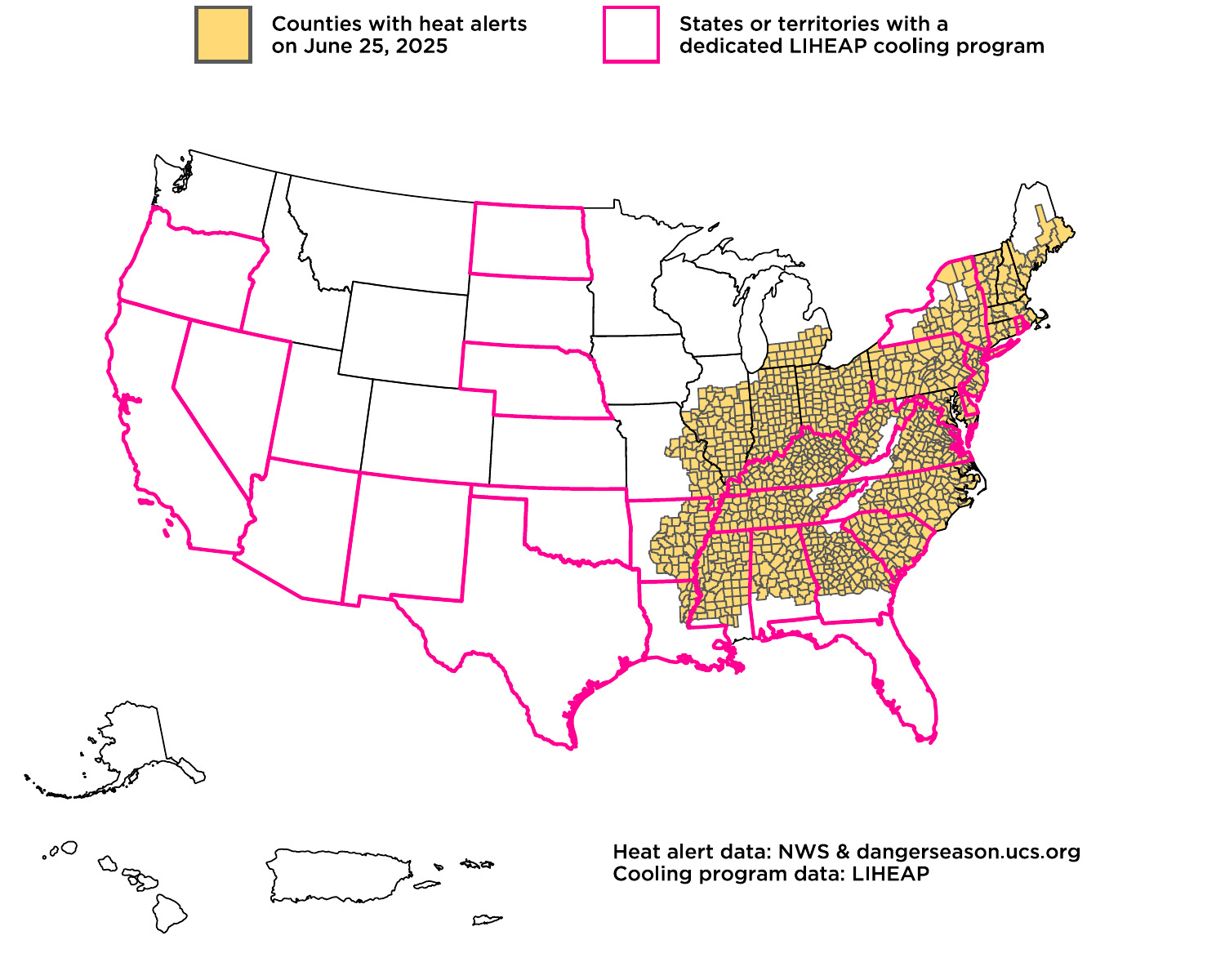

At least one death last week, in St. Louis, MO, is attributed to extended time in a home that had its power turned off by the power company. For people who find themselves unable to pay their electricity bills, the question of whether their electricity provider can shut off their power can become a life-or-death issue. The map below shows the extent of active heat alerts on Wednesday, June 25 overlaid with the 21 states (plus Washington, DC) that have enacted moratoria on hot weather-related electricity shut-offs, illustrating the dangerous gap that low-income households can face—particularly in the 16 states with heat alerts but no protections.

With increasing extreme temperatures, more states are adopting shut-off moratoria; however, a recent study by the Center for Biological Diversity found that power companies that service about 200 million people across the country increased the rate of shut-offs by nearly 21% between January-September of 2023 and the same period during 2024, all the while still taking in record profits. And these shutoffs took place even during the hottest months of 2024.

A nationwide utility shutoff moratorium during extreme heat events would be an important protection for keeping AC and other life-sustaining devices running in a crisis (e.g., refrigerators for food and medication, dialysis machines, respirators), but for consistent access to cooling, many people living with low income also need help paying or keeping up with their electricity bills. For more than four decades, the federal Low-Income Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) has provided grants to states, territories, federally recognized tribes and tribal organizations to support eligible households with utility bills, energy emergencies, and weatherization.

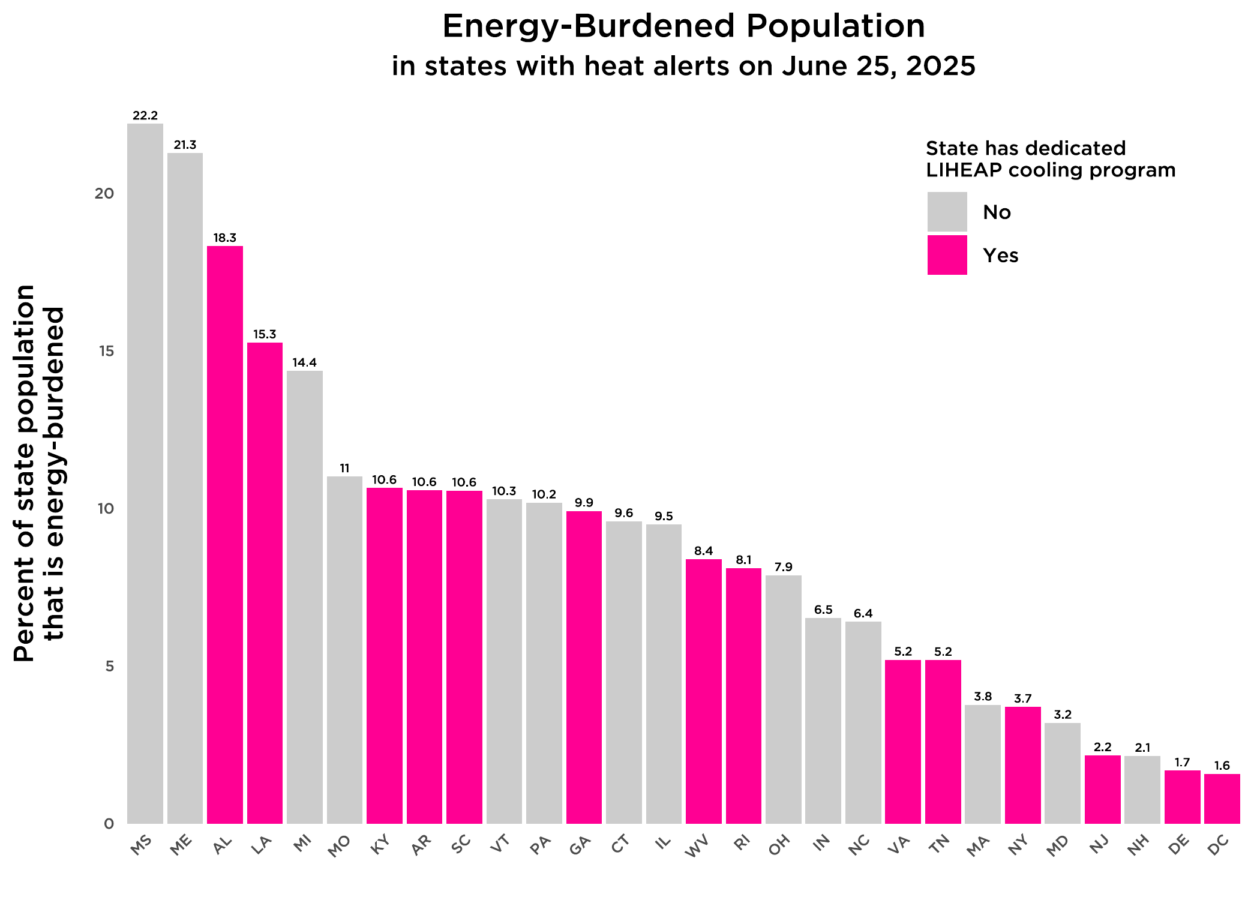

Another way of looking at heat risks to low-income households from hot-weather utility shutoffs is by ranking states by percent of the population that is at an energy burden disadvantage. The Climate & Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST, taken down by the Trump administration but thankfully reproduced here by our friends at EDGI), labeled a community at an energy burden disadvantage if that community ranks very high in energy costs or small particulate pollution in the air, or if they are of sufficiently low income (defined as the 65th percentile of 200% of the federal poverty level).

Sixteen out of the 28 states with heat alerts on June 25 do not have moratoria on hot weather-related electricity shut-offs; at least 10 percent of the population in each of Maine, Alabama, Michigan, Kentucky, South Carolina, Vermont, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut face energy burdens yet they have no protections against electricity shutoffs.

Lack of utility bill assistance during hot weather leaves millions unprotected in many states

States are required to provide crisis energy assistance to residents for winter emergencies, but can opt-in to providing summer or year-round crisis assistance or cooling assistance. Not all states opt in.

With the June 25 heat alerts as a backdrop, this map shows that 23 states plus the District of Columbia are proactively ensuring that LIHEAP funds are available for cooling assistance versus those that only make it available under emergency or crisis conditions—i.e. ,reactively. In states where cooling assistance is available, only three (AZ, DE, GA) have date-based criteria—either specific dates or during summer months.

How are energy-burdened communities under heat alerts protected by dedicated LIHEAP cooling programs? Similar to the utility disconnections bar graph above, below I ranked states according to the population that meets the CEJST definition of energy-burdened communities, but this time I highlight states according to the existence of dedicated LIHEAP cooling programs.

Furthermore, many families who live in public housing do not have ready access to air conditioning in buildings since HUD does not require local housing authorities to meet safe cooling standards for residents. Instead, housing authorities may choose to purchase cooling equipment or set up cooling spaces in common areas. And renters, low-income households, and non-white households are more likely to lack access to air conditioning.

Meanwhile the Trump administration and Congress are aiming to zero out the Weatherization Assistance Program, which helps low- and moderate-income households make energy efficiency improvements that would also help improve cooling and lower energy bills. With many households already struggling to access the program, decimating it would only increase harms to people. Policymakers must shore up this program, as well as scale up investments in safe, climate-resilient, affordable housing.

This past week, millions of people were at risk from extreme heat—in the places they work or where they live and play—and protections to keep them safe offer, at best a patchwork that leaves many unable to obtain resources to pay for air conditioning, avoid utility shutoffs, or get breaks, water and shade at work. The brutal heat experienced last week is becoming more common—and deadly—but the country’s scientific capacity to keep us informed about and safe from extreme weather has been cut down by the Trump administration. Danger Season is upon us, and we need resources to help us be informed and safe from extreme heat.