Over the last few years, I’ve written about our work on the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), a federal program that provides a small amount of compensation to some of the communities that were exposed to radiation from US nuclear weapons activities. Exposed communities have been fighting for decades for the government to address the harm caused by nuclear weapons. And for the past five years, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) has worked with them.

This summer, we finally got a win. After countless trips to Washington, DC, fevered rushes to mobilize advocates, moments of despair (including the entire program expiring), and flashes of hope, RECA has been reinstated and significantly expanded. A congressional source estimated that 125,000 people who were originally left out of RECA will now receive compensation, representing the largest program expansion in history. This expansion doesn’t provide everything communities need, but it is a small and necessary step towards justice, and also a big win in these political times.

This has been a long and often tragic journey for the community advocates at the center of this fight. In some cases, such as those living downwind of the 1945 Trinity Test in New Mexico, people were first exposed 80 years ago and have been fighting for recognition and help ever since. In others, including people living with Manhattan Project waste in their Missouri backyards, this waste may still pose an ongoing risk to people nearby. In every case, RECA advocates and their neighbors have watched countless loved ones get sick and pass away during their quest for support. One of the hardest things about this victory is knowing that it won’t bring back the people who died before they could get help.

People did not need to die or get cancer. We are in this position because the US government recklessly exposed people as they built up the nuclear weapons arsenal—and then lied about it. RECA is an imperfect attempt to offer recognition and some degree of compensation to those who have suffered, but we know that nothing can make up for the loss of a loved one and a life cut too short.

True justice may never be possible, but RECA can still go farther. To appease budget hawks, congressional leadership eliminated compensation for some exposed communities—including Guam and the county nearest the Nevada nuclear test site—and cut health care benefits for claimants. This just pushes those costs off on the people least able to bear them: exposed communities dealing with radiation-linked disease.

The people who were left out of this round of expansion are just as deserving of justice and we’ve already been working with our coalition to try and address some of these holes in coverage in other legislation moving through Congress. But before we shift entirely into the next phase of this campaign, I think it’s important to reflect on how we got here.

How victory was achieved

We learned a lot and made plenty of mistakes along the way, but our coalition also succeeded in many powerful ways:

- Congressional advocacy. We secured deep, lasting bipartisan support for this issue by spending years cultivating members of Congress from across the aisle. We flew advocates and affected community members into DC, held in-district and virtual meetings, adding up to hundreds of meetings with members of Congress, not to mention the thousands of calls and emails sent to congressional offices on this issue.

- Media. Advocates and community members worked hard to tell their stories, make their voices heard, and keep the pressure on legislators through ongoing media coverage that centered community voices. They held press conferences, wrote op-eds and letters to the editor, and gave countless interviews. This resulted in more than 100,000 media stories on RECA between 2020 and 2025, including stories in major national outlets including CBS, NBC, the New York Times, NPR, and the Wall Street Journal, as well as in state and local media in every affected state. Critically, every story included community voices and perspectives, keeping the issue on legislators’ radars and shaping coverage of RECA nationwide.

- Events and other tactics. We got creative! We tied our issue closely to the Oppenheimer film release, seizing a key cultural moment. Congressional champions shared the stories and photos of affected communities on the Senate floor. Advocates attended the 2024 State of the Union address. We organized a cross-country bus trip, in which dozens of Indigenous advocates traveled for 38 hours from Albuquerque to DC. We held prayer vigils and marched through the streets to the US Capitol.

- National coalition. We helped build and sustain a national coalition for years, with diverse members from across the country and across the political spectrum, from all walks of life. This group has shown that in an otherwise incredibly divided time, people can come together, respect and care for each other, and—most importantly—fight for each other. Many in this group have referred to this coalition as a family.

And here’s the trajectory of UCS’s work on RECA, starting in 2020 when we first got involved (and noting that this work only built on decades of prior work by affected communities).

- 2020: Wrote a letter highlighting how COVID was harming radiation-exposed communities. Signed by 150 groups, and led to a meeting with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s (D-CA) office.

- March 2021: House Judiciary Committee hearing, featuring speakers from affected communities. RECA Working Group established.

- December 2021: Markup in the House Judiciary Committee for a bill introduced by Senators Mike Crapo (R-ID) and Ben Ray Luján (D-NM); the bill passes out of committee with a 25-8 vote.

- 2022: Built up co-sponsors on RECA bills, getting more than 100 bipartisan senators and representatives.

- June 2022: Instead of an expansion, RECA is extended for two years as is, until June 2024.

- July 2023: Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) joins the RECA fight, combining his bill to cover exposed communities in Missouri with Crapo and Luján’s larger bill. This joined bill passes as an amendment to the Senate’s National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) with 61 votes in favor.

- December 2023: The RECA amendment is taken out of the NDAA.

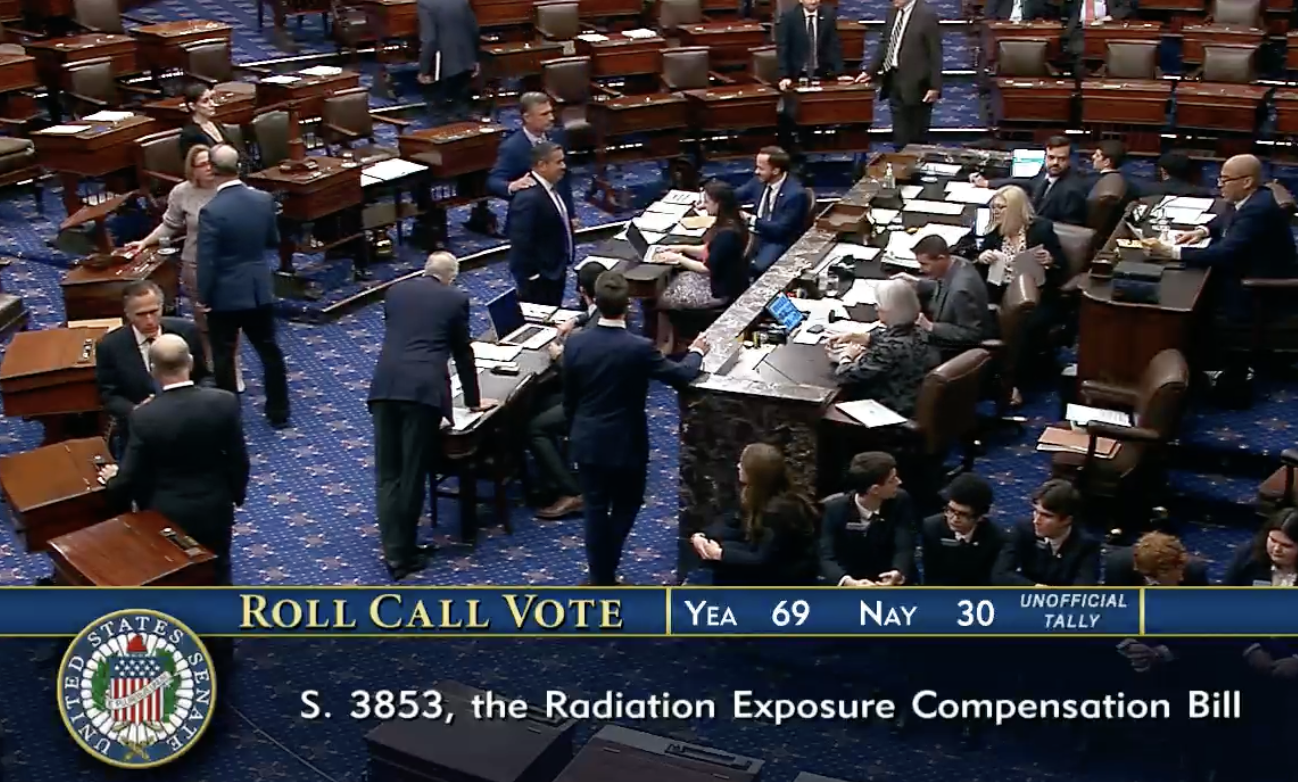

- March 2024: A “stand-alone” RECA expansion bill is brought to the Senate floor, passing with 69 votes in favor.

- May 2024: Our coalition defeats another two-year extension proposed by House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA), as well as bills that would have only covered a handful of communities, in favor of continuing to fight for expansion.

- June 2024: The RECA program expires. Johnson refuses to bring the Senate-passed expansion bill up for a vote in the House.

- December 2024: Flipped the Utah congressional delegation from “no” to “yes” on expansion, clearing the final obstacle in the House.

- July 2025: RECA expansion passes as part of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

There is simply no way this expansion would have passed without the leadership of affected community members who have tirelessly and bravely shared their stories and organized in their communities. It has been a true honor to support this issue and to work alongside my incredible colleagues at UCS and the community advocates who built and sustained this movement for decades. The fight isn’t over, but this win is a testament to the passion, skill, and resilience of these communities and what we can achieve together.

NOTE: This blog post originally reported that the county nearest the Trinity Test site would not be covered under the expanded RECA; it has been corrected to reflect that the county nearest the Nevada test site is not covered.