Many news stories these days are shocking but not surprising, and this week brought one more: Scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and a consortium of universities have measured a dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico (which President Trump has renamed the Gulf of America) of 4,402 square miles. While a nearly Connecticut-sized, oxygen-depleted area of coastal ocean seems decidedly abnormal, the last 40 years of annual measurements—coupled with lackluster efforts to stem the deluge of chemical pollution running off midwestern farms and flowing downriver into the Gulf—made this week’s announcement entirely predictable.

But if there has been depressingly little political will to fix the pollution problem to date, just imagine what will happen if future dead zones aren’t even measured. With the Trump administration’s ongoing decimation of federal science agencies, that’s exactly what could happen.

Tracking a fertilizer-fueled dead zone that won’t die

The annual Gulf dead zone forecast and measurement are part of a project to track progress toward a commonsense goal that the US government, states, and Tribes have agreed to, at least in principle, since 1997. As I wrote on this blog almost exactly a year ago:

Government agencies at the federal, state, and Tribal levels, led by the US Environmental Protection Agency, came together in 1997 to establish the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force (HTF) with the mission of reducing the effects of hypoxia and the size, severity, and duration of the dead zone. The HTF has set a variety of pollution reduction and water quality goals over the years. But the persistent, infuriating truth is that the HTF and its member agencies are not meeting their own targets.

On the contrary, they are failing badly.

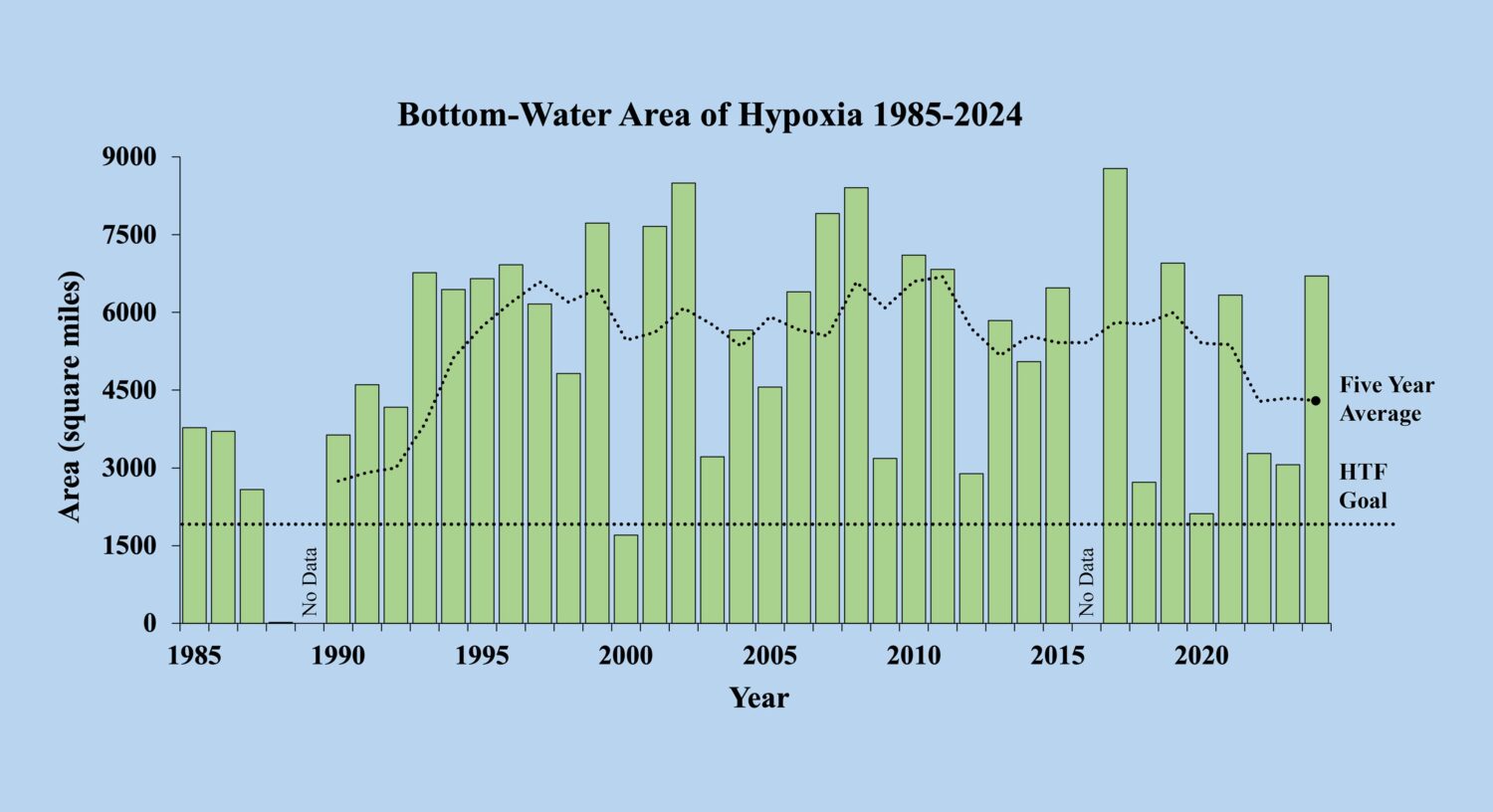

In that blog post last year, I pointed to an earlier version of the graph below as evidence of that failure: it shows the persistence of hypoxia—the lack of oxygen in the waters off the Gulf Coast—from year to year. Now here we are again talking about a dead zone that is still far too big.

The reason it’s too big, in large part, is industrial agriculture’s flagrant overuse of chemical fertilizer. That overuse is responsible for water pollution all across the Corn Belt, even before it flows downstream to the Gulf. A recently released water quality report for Polk County, Iowa, highlights agricultural pollution as a major threat to the region’s rivers, streams, and ultimately its drinking water. The Central Iowa Source Water Resource Assessment found that high nitrate levels, often exceeding federal health limits, are affecting the rivers that provide drinking water for the county and the city of Des Moines, and that the largest contributor is nitrogen fertilizer from farms.

It’s a vicious cycle: Fertilizer overuse degrades the soil and its ability to keep excess fertilizer from running off, which in turn leads to more overuse. Rinse, repeat. A recent study from Iowa State University revealed that nitrogen fertilizer application rates in the Corn Belt have been increasing by about 1.2% every year for the past three decades.

This is bad for drinking water in farm communities and downstream cities. It’s bad for wildlife and recreation in rivers and lakes. And in the Gulf, where fish, shrimp, and other creatures are killed or driven offshore by the lack of oxygen in a dead zone, it’s bad for people who make their living from those resources: A 2020 report from my team at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) found that agricultural nitrogen runoff has caused up to $2.4 billion in damages to fisheries and marine habitat every year since 1980.

Federal agencies and scientists are critical to tracking fertilizer pollution

This year’s Gulf dead zone prediction-and-measurement cycle began, as always, in the spring, when snowmelt and seasonal rains were flushing that excess fertilizer out of midwestern farm soils and into streams across the Mississippi/Atchafalaya River Basin. This vast watershed drains all or part of 31 states (including the Corn Belt) and two Canadian provinces before flowing into the northern Gulf off the coast of Louisiana. Each May, scientists in the US Geological Survey (USGS) National Water-Quality Project sample nitrogen and phosphorus influxes at scores of monitoring stations throughout the drainage basin, and use sophisticated modeling and mapping tools to predict what these will mean for pollution levels in the Gulf later by July.

Scientists at NOAA and partners from several university research groups use those data to forecast the size, location, and duration of the Gulf dead zone likely to occur over the summer, when warming coastal water and microbial activity converge in ways that cause oxygen levels to plummet (i.e., hypoxia). In early June this year, the team predicted a hypoxic zone of “average” size. It’s something of a parlor game, in certain super-nerdy circles, to guess what US state a given year’s dead zone will be compared to—this year, the scientists threw in a twist, predicting a size of 5,574 square miles, equivalent to three Delawares! When the scientists actually conducted the research cruise to measure and map the dead zone from July 20 to 26, they found that it was smaller than predicted in area, but still “widespread and severe” and well over double the size of the goal.

As I pointed out around this time last year, it’s clear that making a dent in the dead zone is going to require new farm policies that compel the agricultural sector to stop flagrantly overusing fertilizer. But it’s also going to require that we keep tracking the problem.

How Trump’s attacks on federal agencies—and science itself—could kill the messenger

This past spring, even as USGS scientists were preparing to carry out their piece of the dead zone forecast project, Elon Musk and the so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) were rampaging through federal agencies, creating havoc that exceeded even my pre-inauguration expectations. In April, they terminated leases for the USGS Water Data Centers, among other office closures. Moreover, reporting in May indicated that as many as 1,000 USGS employees would be laid off in June. Court orders paused layoff plans at many agencies, but they appear likely to move forward soon. It is unclear if there will be personnel to staff the monitoring stations by next year.

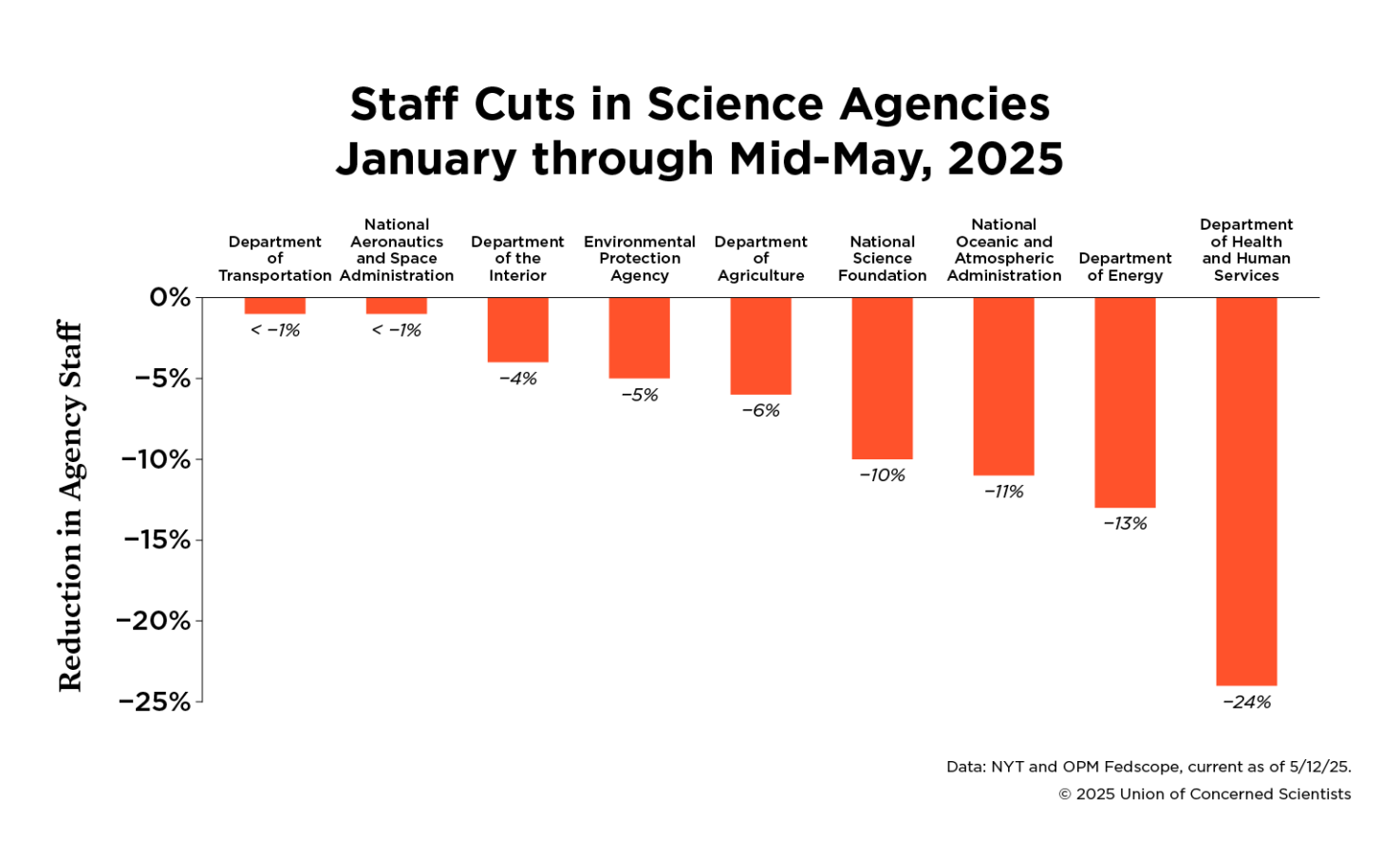

Then there’s NOAA. My colleagues in the Center for Science and Democracy at UCS recently compiled evidence of the Trump regime’s campaign to destroy federal science in its first six months. Among federal science agencies, they found that NOAA has faced some of the most destructive attacks. From the report:

NOAA, the nation’s foremost climate science agency, has faced reckless firing of staff, budget cuts, and slashed resources for climate research, satellite programs, data, and modeling. Under Department of Commerce secretary Howard Lutnick’s watch, the agency’s weather forecasting and climate monitoring capabilities are being undermined and many National Weather Service offices are dangerously understaffed—undercutting critical resources that communities, first responders, farmers, mariners, businesses, and local decisionmakers rely on to protect lives, infrastructure, and economic activity. Critical NOAA data and tools are also being discontinued, including snow and ice data products and climate.gov, a free public portal for essential information on climate science and impacts.

Ditto for the annual Gulf measurement, which is led by Louisiana scientists using a NOAA research vessel, equipment, and funding. It’s one of many important services the agency provides—along with climate science and monitoring, hurricane forecasting, fisheries research, and more—that is now at risk. Staff losses at NOAA between January and May have been dramatic, and President Trump’s proposed FY26 budget for NOAA calls for even deeper cuts.

Congress—which holds the power of the purse—has just begun the process of negotiating the FY26 budget. While it’s promising that a Senate committee recently repudiated the Trump NOAA budget, substantial damage has already been done and we are a long way from agreement on an appropriations bill.

You can tell Congress to protect NOAA from dangerous budget cuts by taking action here.

Meanwhile, the Hypoxia Task Force led by the Environmental Protection Agency may be in disarray, and academic partners who have been critical to tracking the Gulf dead zone could also have difficulty carrying out their work in the years ahead. US universities everywhere are feeling the effects of the Trump regime’s war on science. The team that made the Gulf dead zone prediction includes scientists at four US universities—Louisiana State University, the University of Michigan, North Carolina State University, and William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science—along with Canada’s Dalhousie University. Federal grants have been a critical funding source for many institutions of higher education—in 2024, for example, federal grants reportedly accounted for 57% of the University of Michigan’s $2 billion overall research budget.

Will anyone still have resources for important work like tracking agriculture’s contribution to water quality and dead zones next spring and summer? How will researchers, farmers, fishers, and the public get an accurate sense of the impact fertilizer overuse and pollution is having on our waterways and the Gulf? And how can we hope to hold our government or Big Ag accountable for setting goals that will shrink the dead zone?

Decimating funding for research and public science isn’t just about saving a few bucks—it’s about stripping us of the tools that allow us to understand the full scope of the challenges we face, to advocate for evidence-based policy solutions, and to hold the powerful accountable for the harm they continue to cause. I hope that next summer, when another dead zone will surely bloom in the Gulf, we will at least know about it.