California’s megadrought seems as endless as the Mojave Desert. Between killer heat and growing wildfires, the state experiences some of the harshest effects of climate change. Although California is leading in clean energy policies needed to tackle the worst impacts, water management is still a real problem—for everyone in the country.

That’s because the United States relies on California as its top producer of agricultural products. Meanwhile, growing industrial agribusinesses have worsened pesticide pollution while draining the state’s water supply. Agriculture uses about 80% of California’s water, and it’s unsustainable.

There are solutions, though, and they involve strategic land use planning and repurposing to address California’s social, ecological, and water challenges, especially for its most disadvantaged people.

Ángel S. Fernández-Bou, bilingual senior climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, has spent part of his career studying the problems facing California’s land, including farms, farmworkers, and people. He has devised several solutions that can protect people and help them prosper. They start, he says, with listening to and respecting community and Indigenous knowledge.

Ángel and UCS analyst Erin Woolley, with partner Dezaraye Bagalayos from Allensworth Progressive Association, published a guide last month called Working with Nature to Protect California’s Agricultural Regions: How Nature-Based Solutions Can Build Resilience, which details these plans and shares case studies where communities are already thriving by putting them into practice.

AAS: What worries you most about California’s environmental future?

ÁNGEL S. FERNÁNDEZ-BOU: My biggest concern is the intersection of multiple crises—groundwater depletion, worsening air quality, and intensifying climate extremes, and especially how these affect vulnerable communities, farmers, and the environment.

The San Joaquin Valley has the worst air quality in the country, and we are depleting groundwater reserves faster than they can be replenished. If we don’t act now, we may lose the opportunity to transform California into a global model of agricultural sustainability and socioenvironmental justice.

AAS: What is this new guide you’ve published about?

ÁNGEL S. FERNÁNDEZ-BOU: This guide presents a range of nature-based solutions with multiple benefits to address California’s socioenvironmental and water challenges. It demonstrates how we can work with nature—rather than against it—to create more resilient agricultural systems, protect vulnerable rural communities, ensure water security, and achieve social, environmental, and economic sustainability for the future. And nature-based infrastructure is often cheaper and more resilient than what is called “gray infrastructure,” that is infrastructure based on concrete.

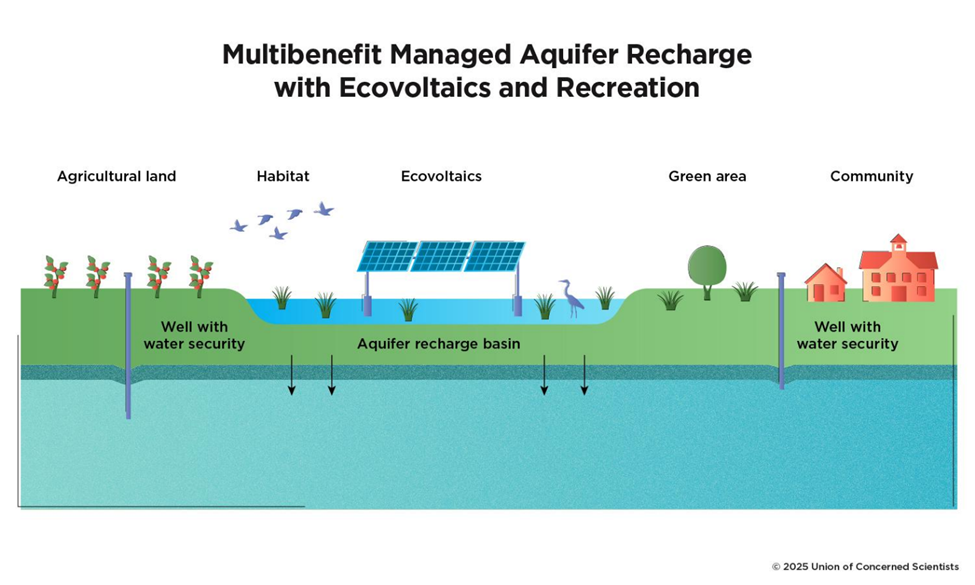

The central approach of nature-based infrastructure is to combine strategic cropland repurposing with other multibenefit projects that can include aquifer recharge, wildlife corridors, solar energy, and buffer zones around disadvantaged communities. These projects can reduce unsustainable water use, improve air quality, create better-paying jobs, and generate new economic opportunities, all while protecting the health of rural communities.

This guide is based on the findings from our recent publication Cropland repurposing as a tool for water sustainability and just land transition in California: review and best practices that presented a framework informed by practitioners and affected groups (communities, farmers, farmworkers, the environment, the economy) for best practices in land transition implementation.

AAS: How do you imagine your recommendations being implemented in different geographic areas of California?

ÁNGEL S. FERNÁNDEZ-BOU: Implementation should be tailored to specific local challenges using different types of nature-based solutions:

For example, floodplain restoration projects can be implemented in areas experiencing flooding, ecosystem imbalance, lack of parks and recreation, or upstream of communities needing natural flood protection. Places like Stockton, California, can benefit from flood protection thanks to the Dos Rios restored floodplain, the newest California state park. The way floodplain restoration works is that it reestablishes the natural connections of rivers with their historical floodplains. As a result, natural river processes safely accommodate floods while infiltrating water to replenish aquifers and maintain steadier river flows over extended periods

Another solution is stormwater basins, which can become parks with multiple benefits that collect stormwater after heavy rains in the wet season while providing recreation in the dry season as green areas. Places like Fairmead, where I helped with a multibenefit stormwater basin project, can benefit from this type of project.

We also have multibenefit aquifer recharge projects, which replenish overextracted aquifers to increase groundwater levels and achieve water security are ideal for regions with groundwater depletion, especially if they have clean and sandy soils and are near rivers or canals. These projects balance out water pumping and water replenishment while achieving other benefits, such as flood control, creating green areas and recreation, improving drinking water quality, restoring ecosystems, and supporting other activities like clean energy generation in ecovoltaics or tourism for bird watching. Places like Teviston in Tulare County, which have excellent recharge potential thanks to their soil texture and have suffered well failures, are perfect candidates.

Wildlife corridors and habitat restoration can connect fragmented ecosystems, improve biodiversity, provide natural pest control for agriculture, and create buffer zones around disadvantaged communities exposed to pesticide drift. I love to go to the Merced Wildlife Refuge near where I live, and there is an effort at present to create wildlife corridors to connect it with the foothills of the Sierra Nevada near Yosemite.

Agrivoltaic systems—which combine solar energy production and agriculture (i.e., crops or livestock) simultaneously on the same piece of land—work well in areas with high solar potential, where farmers need income diversification, or where land repurposing from agriculture is necessary due to water constraints. These allow continued agricultural production while generating clean energy. People can learn more from our fact sheet about agrivoltaics and ecovoltaics.

Agricultural transition to agroecological practices can be implemented where soil health is degraded, synthetic fertilizer and pesticide use are excessive, or communities are experiencing health impacts from conventional agriculture—helping create better-paying, safer farmworker jobs. Some examples of agroecological practices include no-tillage, no toxic pesticides, cover crops, mulching, sustainably integrating livestock, and composting, while treating farmworkers and the environment with respect. Our friends from Allensworth (Tulare County) are implementing this vision.

These and other solutions can address specific local challenges while creating multiple benefits for communities, agriculture, and the environment.

AAS: How can people access resources to put your guide into practice?

ÁNGEL S. FERNÁNDEZ-BOU: There are several funding sources for projects. My colleague Erin Woolley, who coauthored the guide, is our in-house expert.

First, there are federal funds available. The Inflation Reduction Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provide historic opportunities for climate and environmental justice projects. There are also state programs in California like the Land Repurposing Program, Strategic Growth Council funds, and other resources for disadvantaged communities. Lastly, there are public-private partnerships through which companies can invest in renewable energy and clean industry projects that benefit local communities.

AAS: What obstacles might the implementation of these solutions encounter in California?

ÁNGEL S. FERNÁNDEZ-BOU: My main concern for implementation is the inertia of business as usual. We have the solutions, we have examples of successes, and we have amazing people working on this. What we need is the political will to provide more funding and incentives, and the social push to advocate for the best solutions as informed by local people who are affected first-hand by these changes. Community knowledge and needs first, along with farmers’ perspectives, are the best ways to strengthen local economies and restore our environmental health.

The key is developing specific plans with strong local leadership—like we see in Allensworth—and seeking technical assistance to navigate funding application processes.

AAS: Can you share some success stories for these nature-based solutions you’re proposing ?

ÁNGEL S. FERNÁNDEZ-BOU: Yes, we’re seeing promising examples of success:

Allensworth is an inspiring example where the Allensworth Progressive Association is developing an agroecology hub that will create local jobs, improve food security, create a safety buffer/revitalization zone, and strengthen the community economy.

Multibenefit aquifer recharge projects have demonstrated we can effectively store water during wet years for drought use. There is a good example in Okieville that we explain in the guide, but multibenefit aquifer recharge is a very promising solution that is generating a lot of interest.

Agrivoltaic systems are also a very hot topic these days. Outstanding scientists, like Professor Sarah Kurtz from UC Merced, are diving into this kind of work, and many farmers are starting to see how these systems can benefit them.

The Dos Rios floodplain restoration has been the largest floodplain restoration in California so far, transitioning around 2,000 acres of dairy land into a beautiful state park that honors Indigenous peoples with a 3-acre Indigenous garden.

These pilot projects are providing the scientific and economic evidence needed to scale solutions regionally.

AAS: If people take away just one message from your guide, what should it be?

ÁNGEL S. FERNÁNDEZ-BOU: Working with nature is environmentally right, economically smart, and socially just.

This guide demonstrates that we can create better-paying jobs, stronger economies, and healthier communities while restoring our ecosystems and securing water for the future. We don’t have to choose between economic prosperity and environmental health—we can have both if we do things right.

California’s future depends on our ability to reimagine how we use land and water to be sustainable. The solutions exist, many communities are ready, farmers know they need them, and funding is available. That’s what we’re working out now.

As we’ve learned from past civilizations, preserving the natural resilience of the land is what allows societies to thrive for millennia. California can be the example for how the world can build a truly socially, environmentally, and economically sustainable future.