Across the nation, cities and states are struggling to respond to the colliding housing and climate crises. Rising construction and insurance costs and cuts to housing retrofit programs make it harder to build and preserve affordable housing. All the while, extreme heat—the deadliest climate impact—continues to worsen. Policymakers and political leaders must address both of these crises; they must consider the current and future realities of fossil-fueled extreme heat and respond to the housing crisis simultaneously.

How exposed to extreme heat are residents of affordable housing?

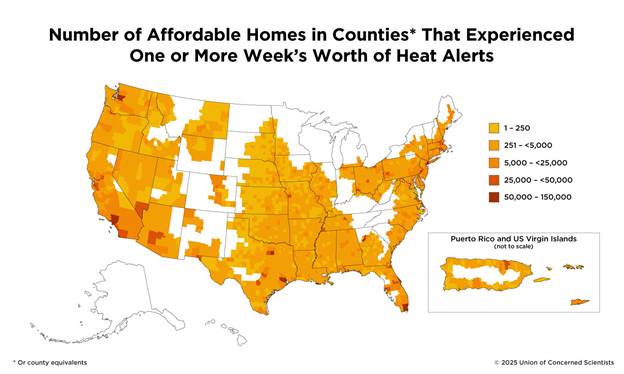

In our new Colliding Crises report, we analyzed the exposure of a subset of affordable housing units—and their residents—to extreme heat. We used the National Weather Service (NWS) county-level heat alerts between May and October 2024, months that the Union of Concerned Scientists calls Danger Season. We focused on the exposure to these alerts by parts of the nation’s housing stock that serve people with low incomes—including public housing, manufactured housing, and housing with other types of federal financing, such as Section 8 vouchers, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), or other programs aimed at providing affordable housing for older adults and people with disabilities.

We found that across the United States, most people living in affordable housing experienced at least 7 days of extreme heat alerts, with nearly half enduring 21 or more days of alerts. The largest shares of the nation’s affordable housing units that faced heat alerts were located in the Northeast and Southeast. Texas, California, and New York have the largest absolute number of exposed homes.

Heat exposure matters

As a nation, we have simply not invested sufficiently in building and maintaining affordable housing for people with low incomes. Large swaths of the nation’s existing affordable housing stock are aging. This housing is of varying construction quality, located in places exposed to heat, facing increasingly frequent disasters, and lacking access to cooling. Meanwhile, plans for new construction of affordable housing aren’t considering measures to protect against climate impacts, such as extreme heat.

Much like inaction on housing has brought us to the current affordable housing crisis, the US government’s insufficient action on climate resilience has individualized risk, putting people’s health and well-being in jeopardy. The dangers of kicking the can down the road are becoming clearer, and will worsen as temperatures rise due to climate change.

Tax credits must incorporate heat resilience

Currently, the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program is the largest vehicle for the creation of affordable housing nationwide. The federal government allocates these credits to state governments who then distribute them to housing developers. Developers compete for tax credits to build or repair affordable housing, and in exchange for those tax credits, rent restrictions are applied for thirty years. Standards for awarding the credits are set by state governments through what’s known as the Qualified Allocation Plans. Going forward, it’s crucial for state governments to align their Qualified Allocation Plans to finance the repair or building of new LIHTC properties with climate realities, considering heat risk, cooling strategies, and the need for backup power as extreme weather events increase.

It’s estimated that tens of thousands of LIHTC-financed affordable homes will reach the end of their 30-year affordability period in the next three years. Hundreds of thousands more LIHTC units will exit the program within a decade once they also reach “Year 30,” the minimum required affordability period. When properties leave the LIHTC program—either by choosing to leave the program early or reaching the thirty-year threshold—their rent restrictions will expire, opening the risk of rent hikes and evictions unless jurisdictions apply new conditions and financing or extend affordability periods.

State and local governments can both keep tenants stably housed and improve the climate resilience of this aging housing stock by offering property owners conditioned incentives to mitigate heat risks after tax credits expire.

We need programs for the most at-risk people

The need for heat-resilient housing development and preservation isn’t limited to the LIHTC program. Funding for heat resilience must be expanded for all affordable housing types, regardless of their financing structure and whether they are owner- or renter-occupied.

Policymakers must understand the populations, places, and housing types that are at greatest heat risk in their region and develop targeted programs and legislation to reduce the risks of extreme heat. In some parts of the country this may look like repairing and replacing older manufactured homes, while in others it may focus on market-rate rental housing to increase the incentives for landlords to reduce heat risk while driving down cooling costs for renters.

The cost of cooling is part of housing costs

All levels of government develop policies and programs based on a narrow assessment of housing costs by studying monthly rent and home sale prices. While a study of those costs confirm that rent is too high and home ownership is prohibitively expensive, these figures don’t account for the much higher, true cost of remaining safely and stably housed as extreme heat intensifies. When developing housing plans, policymakers should develop locally relevant “all-in” understandings of energy and housing cost burden.

Beyond recognizing the true combined cost of energy and housing burden, policymakers must work to reduce it. Federal, state and local energy bill assistance programs must be well-funded and expanded to ensure that families living with low and fixed incomes can afford to pay their electricity bills and run their air conditioners when needed. The Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) is a crucial lifeline, but it needs to be bolstered and expanded, especially to cover cooling costs (in addition to home heating costs). State legislatures must develop life-saving laws, to prevent utility shutoffs for non-payment of bills during periods of extreme heat. Our analysis lists several additional policy recommendations to protect the health and safety of people residing in affordable housing.

The opportunity ahead

The Trump administration’s attacks on climate science, resilience, and clean energy policies and investments while boosting fossil fuels are only increasing costs and risks across the nation. In this context, the kind of comprehensive action needed to increase our collective climate resilience may seem difficult, but inaction will be deadly.

Responses to the housing crisis represent an opportunity to take action to increase climate resilience and save lives. There is bipartisan support for taking action to address the acute affordable housing crisis in our nation. As lawmakers in Congress consider housing bills, they must ensure that any new laws, policies, or programs serve the needs of families living with the lowest incomes and incorporate climate resilience measures to protect people living in the face of the worsening climate crisis.

Juan Declet-Barreto, Amanda Fencl, and Rachel Cleetus contributed to this blog post.