I was hoping to wrap the year stress free. Instead, I was biting my nails while my partner drove through Winter Storm Ezra, white-knuckling the steering wheel on the way to a family celebration in western Pennsylvania. And I wasn’t alone: across the Midwest, Great Lakes, and Northeast, that storm—also called Bomb Cyclone Ezra, due to its central pressure dropping so rapidly in a short amount of time—wreaked havoc as 2025 came to a close.

Blizzard conditions dumped more than two feet of snow in some areas, like Michigan. Ice, snow, and low visibility across much of the region brought ground and air traffic to a halt in the midst of the peak of the holiday travel season. Temperatures dropped up to 50 degrees Fahrenheit in less than 24 hours in some parts of the Midwest like Minnesota, down from rather balmy temperatures just before the storm. Those temperature and pressure differences caused severe thunderstorms and high winds, with gusts up to 79 miles per hour (mph) recorded in New York, and even a few tornadoes in Illinois. Those winds, in turn, snapped trees and powerlines, cutting power to as many as 350,000 customers, most of them in Michigan and New York.

In a nutshell, Ezra caused delays, disruptions and inconveniences, but it was not the worst of its kind. If it had been part of the analysis of extreme weather events and their implications for the electricity grid in the central United States we are releasing today, it may not even have made it into the “top ten” worst outage events, bad as it was. What concerns me, however, is just how common these kinds of extremes are becoming, and how often the lights do go out.

All of the 10 largest power outage events over the studied decade occurred since 2020

We examined the 10 largest power outage events in the study area: a region we defined by the territory served by the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), plus a few small adjoining areas in Illinois with planned or already built grid interconnections, hence called “MISO+”. The largest power outage events were defined as those when the greatest number of customers are without power on a single day. For each of these events, we wanted to better understand the experiences of communities and what happened to the grid. What we found is that each of these “top ten” events lasted for multiple days and was associated with compound weather events occurring over a large geographic region. Let’s take a closer look at each of them, in chronological order:

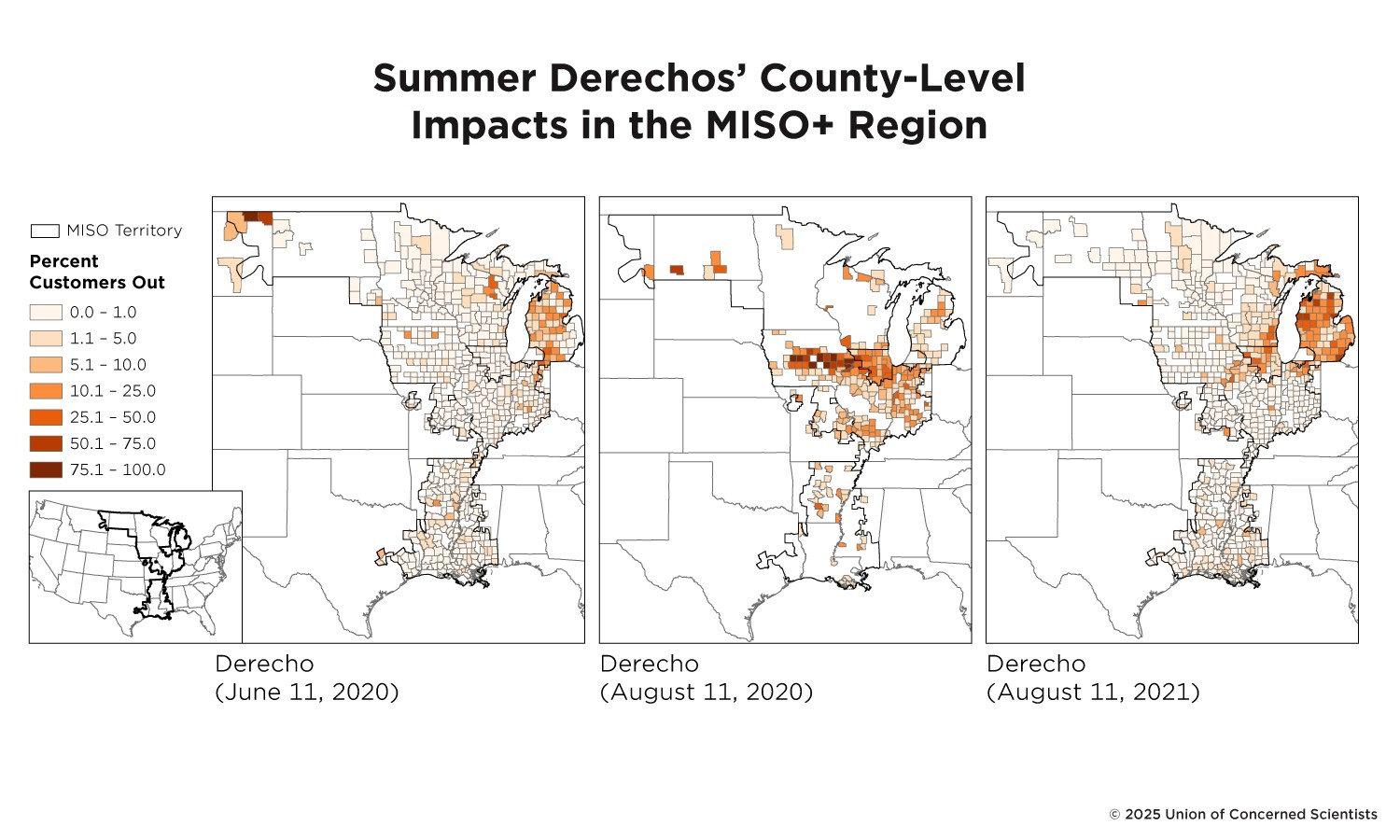

June 11, 2020 – Derecho.

A long line of severe thunderstorms leaving widespread damage from high winds is commonly known as a derecho. The remnants of Tropical Storm Cristobal combined with an upper-atmosphere low pressure system over the Great Lakes region to produce a derecho, wind gusts of up to 75 mph, hail, several confirmed tornadoes in Illinois and Ohio, and another in western Pennsylvania rated an EF2 (the intensity of tornadoes is measured by wind speed and the associated severity of damage, using the Enhanced Fujita, or EF, scale). More than 450,000 customers lost power over the course of the two-day sequence of heavy thunderstorms, most of them in Michigan. The derecho damaged trees, downed power lines and poles, wrecked roofs and buildings, and blew over several semitrailers. Cristobal was one of the westmost-tracking tropical storms ever recorded, and the derecho it produced was the third to hit the United States in a single week’s time.

August 11, 2020 – Derecho.

Two months later, another derecho crossed parts of South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. The worst-hit areas in central Iowa to north-central Illinois experienced average wind gusts of 70–80 mph, with maximum wind gusts of over 100 mph. In addition, the event produced 26 weak tornadoes rated EF0 to EF1, with wind speeds reaching between 65–110 mph in Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana. On its worst day, nearly 1.7 million customers across the Midwest were left without power. Together, these storms caused a few dozen injuries and catastrophic wind damage to trees and crops, particularly in Iowa and Illinois, resulting in what was then the costliest thunderstorm event ever recorded in the United States, estimated to cause at least $11 billion in damages. According to the National Weather Service, “Damage to power lines was also so extensive that power outages were visible from space at night. . . . Widespread, long-duration power outages occurred across the area, with some parts of Cedar Rapids [Iowa] without power for about two weeks.” Some cities experienced extensive loss of urban tree cover, and this loss of canopy “impacted socially vulnerable populations at a higher rate.”

August 27, 2020 – Hurricane Laura.

This late-August hurricane attained tropical storm status in the Caribbean and crossed the Florida Keys as a Category 1 storm, then explosively intensified during its passage across the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall in Cameron, Louisiana, as a Category 4 storm on August 27. At the time, it was the strongest hurricane to strike Southwest Louisiana since records began in 1851. The storm moved inland, spawning at least 16 tornadoes in Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama. Overall, there were 7 deaths directly attributed to the storm and another 34 indirect deaths from causes such as carbon monoxide poisoning, storm cleanup–related activities, electrocutions, and heat stress. Coastal areas of Louisiana and Texas experienced extensive flooding and wind damage to homes, trees, power lines, poles, and industrial facilities, adding up to $19 billion across the United States. In Louisiana and Texas alone, 568,000 households lost power, and nearly 47,000 customers still had no power three weeks later when Hurricane Sally hit the region in mid-September.

October 10, 2020 – Hurricane Delta.

Only six weeks after Hurricane Laura struck, Hurricane Delta hit Louisiana again, making landfall near the previous site. While a weaker hurricane than Laura, Delta brought significantly more rainfall and flooding, affecting parts of eastern Texas, southern and central Louisiana, and portions of Mississippi and Arkansas. Drainage ditches still clogged by debris from the earlier storm worsened overland flooding, and the outer bands of the storm spawned tornadoes in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and as far as the Carolinas. The hurricane caused 6 fatalities, an estimated $2.9 billion in insured damages across the nation, and probably several billion dollars more in uninsured losses. Hundreds of thousands of customers lost power, mostly in Louisiana and some in Texas and Mississippi. Power was also lost to oil and gas production facilities, refineries, and transmission lines.

October 29, 2020 – Hurricane Zeta.

A couple of weeks later, yet another hurricane made landfall in Louisiana. A fast-moving Category 3 hurricane, Zeta caused most of its damage by wind and less from flooding. As the latest and strongest major hurricane and the sixth to make landfall in the United States in a single year (four of which hit Louisiana), Zeta set many records. Overall, it caused about $3.9 billion in damages, and due to the extensive wind damage, more than 2.2 million people lost power in the United States. Some 86,000 customers were still out of power five days later. The storm’s path was nearly identical to that of Hurricane Delta, thus compounding damages and disrupting or even undoing recovery efforts, which further drained private and public financial reserves.

August 11, 2021 – Derecho.

Two rounds of severe thunderstorms swept across a 770-mile swath from southeast South Dakota and northeast Nebraska through Iowa and on to northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, northern Indiana, southern Michigan, and western Ohio that day. The first brought hurricane-force wind gusts along a long line of high-wind thunderstorms (a derecho); the second was accompanied by intense rain and flash floods. Overall, 2 million customers lost power, including 850,000 in Michigan alone. Several hundred thousand were out of power for three or more days. The event was estimated to have caused at least $11.5 billion in damages.

August 30, 2021 – Hurricane Ida.

On August 29, the sixteenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Ida made landfall near Port Fourchon, Louisiana, and devastated Grand Isle. The storm had rapidly intensified during its passage across the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall as a Category 4 hurricane but steadily weakened as it moved inland across Louisiana, Mississippi, and onward on a northeasterly path. Along its course, it spawned at least 35 tornadoes and tied for second with Hurricane Laura behind Hurricane Katrina as the most destructive storm to affect Louisiana. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) attributed to the event 55 direct deaths, plus an additional 32 indirect deaths, and estimated a total of $75 billion in damages in the United States, $55 billion in Louisiana alone. In Louisiana, more than a million households lost power. A month later, 10 percent of the customers in the most heavily damaged areas along the Gulf Coast were still without power. One news analysis showed that most deaths were due to heat, as people could not get relief through air conditioning.

December 16, 2021 – Severe Thunderstorm.

A spate of intense thunderstorms caused by a “low pressure system of historic strength” and accompanied by high winds, tornadoes, and wildfires wreaked havoc from the Rocky Mountains to the Great Lakes, with the worst damage reported across Minnesota, Iowa, and Nebraska. The storms tore off roofs, overturned trucks, shut down interstate highways and air transportation, damaged homes, and injured a small number of people. Hurricane-force gusts brought down power lines, leaving more than 400,000 customers without power across the central United States, mostly in Wisconsin and Michigan. One news report noted, “A tornado in southeastern Minnesota was the first ever reported in the state in the month of December, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data. Record heat much farther north than expected this time of year fueled the storms.”

August 30, 2022 – Severe Thunderstorm.

A line of severe thunderstorms across southern Michigan, with 70 mph winds, caused widespread damage to trees and electric power poles, resulting in extensive power outages. According to the National Weather Service, “Peak statewide outages were around 650,000 at one point, making this one of the higher outage-producing severe weather events for the state.”

February 23, 2023 – Severe Winter Storm.

A harsh, multiday winter storm brought significant icing, strong wind gusts, and heavy snow across a swath from Southern California, through the northern Plains and the Great Lakes region, to the Northeast. Across this region, more than 1 million households lost power. Wisconsin’s governor, Tony Evers, declared an “energy emergency” to allow for faster and more efficient restoration of power. In Michigan, where power outages were most extensive, freezing rain and ice had brought down trees and power lines. The storm system also caused widespread disruptions of air traffic and road transportation. At the same time these severe winter conditions occurred across the Northern part of the country, some Southern states set numerous heat records.

Extreme weather events repeatedly drove widespread power outages over the last decade

Between 2014 and 2024, our analysis shows, each of the top 100 worst days across the central United States in terms of the number of customers affected by an electricity outage was associated with a large-scale extreme weather event. Each one. Take that in for a minute.

Severe thunderstorms (including ones that generated long lines of them, called derechos), tornadoes, high wind events, hurricanes, and winter storms frequently interfered with the availability of power for hundreds of thousands of energy customers, often for multiple days. More than half (57 percent) of the worst events occurred in summer, but the other seasons saw their fair share (13 percent in spring and 15 percent in both fall and winter).

Oddly, grid operators in the region use bad winter storms as “model” extremes to plan and prepare for grid disruptions. They are not even the most common type, and still, the grid doesn’t do well even when they occur.

Common trends across major power outages

So, what do we make of this series of worst outage events? I see at least 5 cross-cutting take-aways:

The most damaging events are nearly always caused by compounding disasters. In the ten worst outage events we reviewed, it is never merely a severe thunderstorm or a hurricane alone that leads to these extensive outages. Rather, it is a derecho with multiple tornadoes and wildfires. Or it is a hurricane with tornadoes, coastal- and inland-flooding, follow-on fires, and extreme heat or damaged industrial facilities causing a release of toxins. Several events coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, profoundly complicating emergency response, sheltering, and recovery. This has important implications not only for disaster preparedness and emergency response in general but for utility operators in particular as they reconsider their plans and responses to complex disasters.

Mortality from these extreme events is often much higher than reported by official sources. In addition to the direct deaths associated with floods and storms from causes such as drowning or being struck by falling debris, there are many indirect deaths from electrocution from downed live wires, carbon monoxide poisoning (often in winter) or extreme heat (in summer), when electricity for cooking and heating/cooling is offline for extended periods of time. Elevated death rates are being observed for years after such disasters due to the impacts of the added stress, disruptions in health care, lack of infrastructure, poor living conditions, and so on.

Disasters worsen social inequities in multiple, compounding ways. Indirect and post-disaster morbidity and mortality are greater for the more socially vulnerable members of the community. When their homes get damaged, they often do not have anywhere safe to go. The direct disaster effects and long-term stressors during a lengthy recovery period cause more harm to those with preexisting health conditions and lesser economic means than healthy, well-off members of society. And while the worst storms can damage the homes of everyone in affected areas, news reports often point to the devastation caused by high winds and floodwaters, especially to mobile homes, which lack a strong foundation and are built from weaker materials. Mobile homes are, of course, predominantly occupied by lower-income families. Damages to apartment buildings, affecting renters with often limited options to relocate, are also frequently reported. And news reports suggest that areas occupied by lower-income homes, businesses, and renters often have to wait the longest for power to be restored after disruption. Additionally, the wind-dominant events included in our analysis frequently caused extensive damages to crops and farm buildings across the central United States, adding financial losses and burdens to many farmers who already face precarious economic conditions.

The climate-change drivers underlying these extreme events and resulting in costly outages are rarely discussed in news reports. Nearly all of the ten worst outage events were associated with high winds, although floods, fire, and ice also contributed substantially to grid system damages. Where high winds dominate, damage to the grid results either from trees falling on power and transmission lines or from winds directly bringing down poles and lines. Their repair and replacement may be among the biggest factors driving recent increases in electricity prices. While news outlets readily report historical records being broken by these weather extremes, the underlying driver that systemically fuels these costly extremes—climate change—is rarely named in the news reports reviewed.

As grid-damaging storms occur more frequently, areas that have experienced damages have little time to rebuild before the next extreme event and therefore are more vulnerable to deeper losses. The ten worst outage events all happened in the latter five years of the study period, several of them affecting the same areas in the same year (e.g., the record-breaking hurricane season of 2020). This means that people’s homes have been covered only by tarps, not solid, new roofs; water-damaged structures have not yet dried out; and dunes have not re-formed, allowing coastal surges to reach deeper inland. Where there is extensive tree damage, urban canopies have not regrown; forest economies are disrupted for years; and poles and power lines have been barely replaced (if at all) and are prone to being damaged again. The results are long-term depletion of people’s savings, losses to local economies, heavy financial burdens, disruptions of livelihoods, long-term health consequences for individuals and families, including the mental health burden of living through repeated traumatic events and other social consequences for affected communities.

Let’s break this vicious cycle

Taken together, our findings reveal that grid resilience has been strained repeatedly over the past decade—with outages again and again followed by repair costs, again and again. Who suffers the most from these events is typically those who are most socially vulnerable. When extreme events strike, their physical impacts can compound histories of uneven investment, exclusionary planning, and data gaps that obscure who suffers most when power systems fail. Energy justice highlights the intersection of the inequities in housing, health, labor, and socioeconomic geographies that have come to determine whose lights go out first, whose are restored last, and who can cope least with the losses from such outages.

It doesn’t have to be that way, and we should not accept this status quo. We can—and must—strengthen grid resilience by wisely planning ahead for a climate-changed future. We must harden electricity infrastructure and begin by investing in historically underinvested communities, giving those communities meaningful opportunities to engage in the planning and decision-making process. Our goal should certainly be to improve disaster planning and preparedness, response, and recovery. But short of more fundamental rethinking of how to plan the electricity grid for the future and directing resources toward underserved places, the health, well-being, and economic vitality of repeatedly affected communities and regions will continue to be undermined.

So, let’s hold grid regulators, planners, and operators accountable. Let’s demand that they plan for more and worse weather extremes in the years ahead while they bring more renewables and back-up storage batteries online. Climate change is expected to intensify many of the extreme weather events that drove these past catastrophic power outages, heightening physical and social vulnerabilities across the region. As the climate warms, the same inequities that shaped past disasters risk being amplified by more frequent and severe events. Unless we break that vicious cycle.

Let’s make sure the only candles lit this time of year are for holidays and celebration—not survival.