Those of us who live in the central United States are all too familiar with extreme weather events and their implications for the electricity that powers our homes and businesses. Off the top of my head, I can think of several storms that cut the power to my home in Wisconsin, including a particularly severe form of thunderstorm called a derecho in June of 2022. That storm downed a tree that fell within feet of my house, required my family and I to shelter in place amidst a tornado watch, and left tens of thousands of customers without power during a heatwave that followed in the storm’s wake.

As a result of human-caused climate change, severe thunderstorm activity of the kind that hit in June 2022 is expected to increase in the Midwest in the coming decades. And severe thunderstorms are not alone: many types of extreme weather events are projected to intensify.

My colleagues at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) who work on grid modernization–colleagues who are in the room when decisions are made about where and how to invest in our power system–have become increasingly alarmed by the projections for these kinds of extreme weather events and the lack of preparedness of the electricity grid for our climate changed future. Their alarm came to a head five years ago following Winter Storm Uri, in which hundreds of thousands of central US residents lost power during a historic disaster that tragically led to hundreds of deaths. The storm revealed the perilous costs of neglecting our bulk transmission system–infrastructure that transports electricity from long distances, which can make electricity available to regions contending with an extreme weather event by transporting electricity from other, unaffected areas.

In response to this preparedness gap, my colleagues and I have been building a series of analyses and resources to both bring attention to this critical issue and equip power system regulators and operators in the central US with scientific information that can help chart a safer path forward. Building upon our previous report that examined the current state of transmission system planning for climate risks in the central US, we dig deeper into what those climate risks are and their implications for communities in our latest report, “Power After the Storm: Achieving Grid Resilience in a Climate-Changed World.”

In this report, we examine which extreme weather events have historically caused the most major power outages in the central US, how those kinds of extreme weather events are expected to change in the future because of climate change, and how major, power outages, driven by extreme weather events, have affected communities in this part of the country. With this analysis, we create a sketch of what the power system in the central US is up against and what decision makers need to prepare for to keep the power on.

Unpacking a Decade’s Worth of Outage Data

We started by using extremely fine-scale, historical power outage data together with a media analysis to determine which extreme weather events have been most consequential for power outages in the central US over the last decade.

We focused largely on the territory served by the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), which is a federally-regulated entity that oversees the maintenance and build out of the high-voltage regional electric grid and coordinates the transmission of electricity for more than 45 million residents in the central US, from Minnesota all the way down to Mississippi. Based on the spatial data that were available from the US Energy Information Administration to define MISO’s territory, and the somewhat unclear definition of what is and is not within its jurisdiction, some counties that are actually served by the entity may not have been included in the analysis. Furthermore, because of existing and planned transmission interconnections, we include several counties in Illinois that are not within MISO’s territory; we thus call the footprint of our analysis “MISO+.”

To identify the most consequential power outages of the last decade for MISO+, we used county-level information on power outages–in terms of customers without power – from the US Department of Energy. The data span 2014-2024 (slightly longer than a decade, but for simplicity’s sake, we refer to our analysis as having covered the last decade). For each county, we determined the peak number of customers without power for each day of the time period studied. We then totaled that peak number up for all counties across MISO+ to determine the maximum number of customers that were without power for each day. Finally, we sorted those values to identify the “worst power outage days” in terms of the maximum daily number of customers without power.

We looked into media reporting over the region to make sure that we captured real events that were not just a data blip and then used an analysis of local and regional media, as well as government reports on these events, to determine the causes of the top one hundred worst power outage days.

Next, we were interested in examining the top ten worst power outage events more closely to understand their consequences and what transpired. As some of those worst days were caused by the same extreme weather events with power outages lasting for multiple days, we selected the top ten unique power outage events from the top one hundred list and conducted a deeper review of media and other reports to determine what can we learn about the patterns of impacts from these most consequential outage events.

Finally, using the results of our initial analysis, we conducted a review of scientific literature to consider how the extreme weather events that were most consequential for power outages in this region over the last decade are expected to change moving forward because of human-caused climate change.

What We Found

The results of our analysis were surprising, even for those who are steeped in these issues. We found that every single one of the top one hundred worst power outage days were caused by extreme weather events, oftentimes severe thunderstorms, hurricanes, or severe winter storms. While it is not news that extreme weather events cause power outages, there are other things that can be the culprit (think, the massive 2003 blackout in the Northeast US that was caused by a software bug).

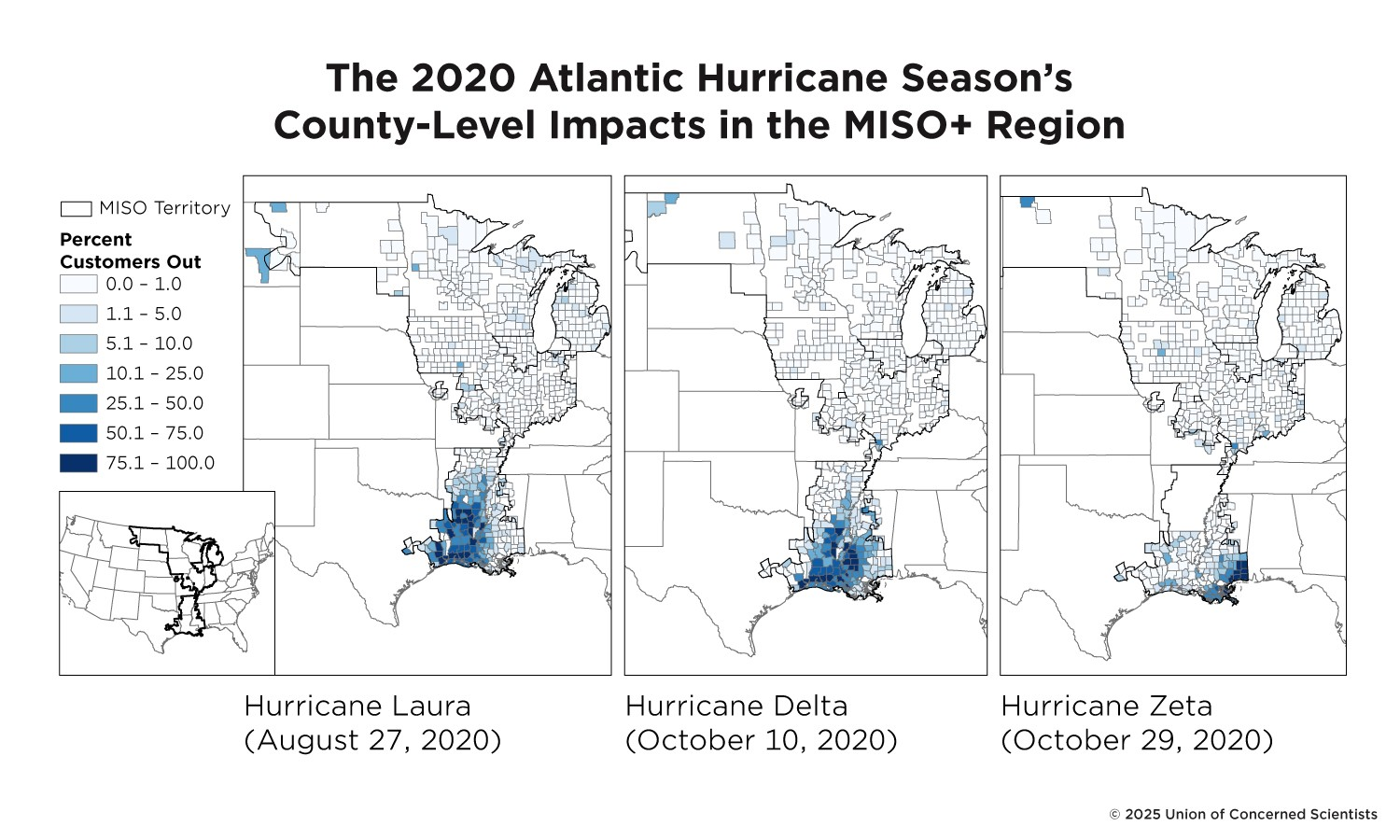

We also found that many of the power outages were caused by back-to-back extreme weather events that left communities with little time to recover. For example, during the 2020 hurricane season Hurricanes Laura, Delta, and Zeta knocked out power in communities across Louisiana in short succession of one another. The tragically deadly storms left hundreds of thousands of people without power, costing the country billions of dollars in damages.

The 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season’s County-Level Impacts in the MISO+ Region. Source: UCS

We further found that the historical inequities that have left some communities more vulnerable to power outages are at risk of being amplified if we do not consider such inequities in the investments that we make in our power system moving forward.

In the future, many aspects of the extreme weather events that caused the most consequential power outages of the last decade are projected to worsen because of human-caused climate change. For example, in many parts of the central US, severe thunderstorm activity is expected to increase, and the hurricanes that make landfall are expected to bring increased rates of precipitation. Furthermore, snowstorms may intensify in places where they continue to occur in the decades to come.

You can find more details about our report findings here.

Science-based planning can save lives

Given that the central US is expected to see more of the very extreme weather events that have caused the region’s worst power outages, our report highlights the urgency for power system regulators, planners, and operators to take climate change into account and work towards building the grid’s resilience to these increasingly frequent, high-impact events. Anything else would be frankly negligent, wasteful, and would continue to put communities in harm’s way.

In our report, we highlight the need for science-based grid resilience planning. While we provide a sketch of the kinds of impacts that the MISO+ region is expected to face, it is critical that power system regulators, planners, and operators use the vast array of climate science information that is available to develop detailed risk assessments. We note the fact that the collection and study of data on extreme weather events–the information needed to make informed investments–are threatened under the Trump administration, demanding that those responsible for keeping the lights on stand up for the science that they rely upon.

Given the fact that climate change is largely driven by the burning of fossil fuels, and the fact that the power system is a major consumer of those fossil fuels, we also highlight the critical need for a transition to an electricity grid powered by clean energy. As another UCS analysis of Winter Storm Uri showed, fossil fuels are by no means a guarantor of grid resilience, as those power sources failed at a higher rate than renewable energy sources. And, of course, while we continue to use those fossil fuel sources, we are also making the problem of extreme weather worse. So, switching to renewables will help the power system avoid the worst impacts of climate change and help the system hold up when extreme weather events occur.

Finally, we stress the importance of MISO and the states that fall within its territory engaging communities in grid resilience planning. Doing so would ensure that investments made are allocated where they are most needed while supporting the development needs of vulnerable communities, ensuring they are not left behind by resilience building.

The reality of climate change is that we know enough to act.